Silly Symphonies: The Oscar-Winning Disney Animation Series That The Studio Forgot

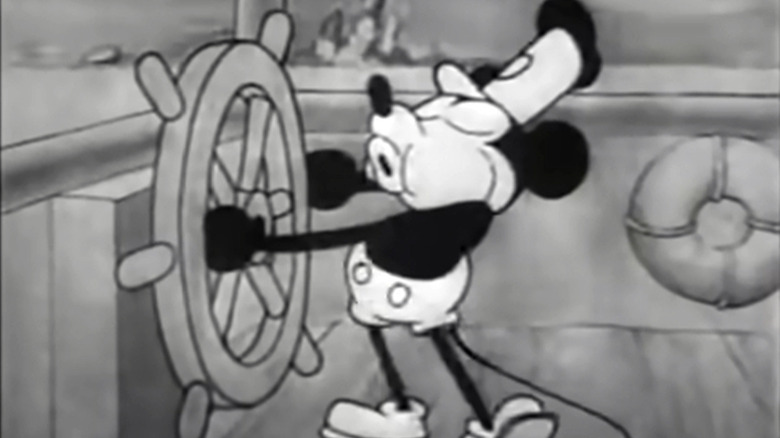

(Welcome to 100 Years of Disney Magic, a series examining the history, achievements, and legacy of The Walt Disney Company over the last century. Part 4, "Disney's Steamboat Willie Didn't Just Revolutionize Mickey Mouse — It Revolutionized Cartoons," examined the history of one of the most globally recognized icons ever created. In Part 5, we look at the next stage in Disney's history: the Silly Symphonies.)

As someone who is more interested in the history of the Walt Disney Company than its recent offerings, I've noticed some interesting gaps in terms of popular coverage. When people do talk about the company itself and its early contributions to the world of animation, the conversation is usually focused on the Mickey Mouse shorts and "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs." If a nerd film historian is really showing off their deep understanding of Disney lore, they may also bring up Oswald the Lucky Rabbit or even the Disney Brothers Studio's first hit, the Alice Comedies.

For whatever reason, the time between "Steamboat Willie" debuting in 1928 and "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" in 1937 isn't really talked about in the fandom circles. I found a few documentaries on YouTube, including the making of featurette "Silly Symphonies Rediscovered," but nothing that had more than about 11,000 views. Contrast this with the Silly Symphonies shorts themselves, which have tens of millions of views, even when uploaded by unofficial channels (this may be because they are categorized as "YouTube Kids" content, but that's a whole other rabbit hole). There are countless "the dark history of" or "the truth behind" style videos that purport to cover the company's salacious past (with varying degrees of accuracy), and many of these have hundreds of thousands of views.

What gives?

The Silly Symphonies were Disney's testing grounds

The Walt Disney Company made history with the Silly Symphonies — although you wouldn't know it by the company's marketing. Heck, the Disney100 promo video completely skips this decade. Other than the obligatory "Steamboat Mickey" shot, it basically skips everything pre-1940 — which is an embarrassing self-own second only to the gratuitous amount of Marvel Cinematic Universe and "Star Wars" content (guys ... you bought those established IPs in 2009 and 2012 respectively. No one looks at Han Solo and says, "yup, the epitome of Disney magic right there.")

Yet, the Silly Symphonies — and not the Mickey Mouse shorts, which were also being produced at the same time — is where the animators at Hyperion studio in California really got to experiment in the medium and break new ground. Sure, Mickey and Minnie were breakout characters, but Disney had failed enough times in Hollywood to know better than to put all his eggs in one basket. He'd tried relying on a single series with the Alice comedies and then Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. This time around, he'd have two projects on the go: the main series with his star attraction, and a second series of independent, unrelated stories where his animators could try out new content and techniques.

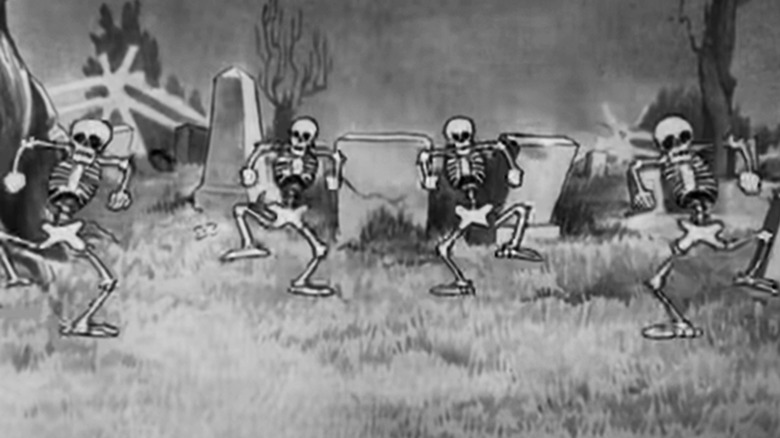

The result was films like "The Skeleton Dance," "The Three Little Pigs," "The Cookie Carnival," and, my personal favorite, "Music Land" (all of which are available on YouTube). It's hard to watch these shorts and not be impressed: they are brimming with creativity and passion. It's clear these were the highest achievements in animation during the '30s, and as a result, they hold up extremely well.

The Skeleton Dance makes silly, symphonic history

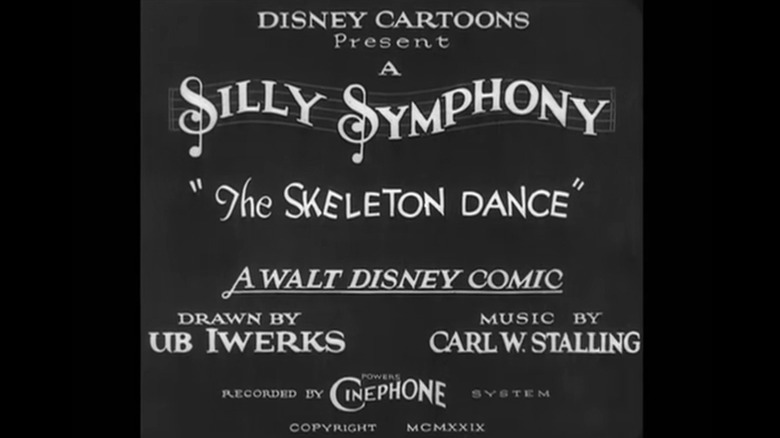

Walt's development of the Silly Symphonies project began shortly after the debut of "Steamboat Willie." The first film in the series is also probably the best-known: "The Skeleton Dance." Referred to affectionally as "the spook dance" in Walt's correspondence, the story was the brain-child of animator Ub Iwerks and composer Carl W. Stalling.

Stalling was an old acquaintance of Walt's from back in Kansas City, whom Disney had contracted to do the scores for the original two Mickey Mouse shorts, "Plane Crazy" and "The Gallopin' Gaucho." Neal Gabler ("Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination,") credits Stalling with the initial idea for doing the "Sillies" (as they are sometimes called), as well as the basic premise for the first film, "The Skeleton Dance":

What Stalling had proposed was a "musical novelty" — a cartoon that began with the music and had the action animated to it. And he had a subject for the first installment as well. As a child Stalling had seen an ad in The American Boy magazine for a dancing skeleton ... The image had stuck with him, and he suggested that Walt animate a group of skeletons dancing to one of Stalling's own compositions. ... The image stuck with Walt too.

Ub Iwerks was tasked with animating the film, and — to Walt's annoyance — he insisted on doing it all himself rather than having junior animators handle the in-between action. The result was a fun film full of nifty innovations: the skull jumping out toward the audience, the choreographed dancing, and the playing with shadows and perspective.

The backbone of Disney in the '30s

In "Walt's Arcadia: The Silly Symphonies" (published in the collection "The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Movies 1921—1968"), Daniel Kothenschulte describes "The Skeleton Dance" as a "true celebration of the medium," highlighting Iwerks' skills as an artist:

The way in which "The Skeleton Dance" and "Hell's Bells" — both drawn and directed by star animator Ub Iwerks in 1929 — play with frightening motifs is accomplished through basic artistic means of expression; they fascinated the general public, as well as some of the most distinguished film critics.

By the end of the '20s, a major shift had taken place in the animation industry. As Walt Disney Productions (as it was renamed in 1929) entered the '30s, it was poised to take over as the dominant player in the field. The biggest competitors from the silent era were Pat Sullivan's Felix the Cat series and the Fleischer Brothers' cartoons — but both really struggled with the transition to sound. There was an opening in the market and Walt Disney was racing to make best use of this opportunity.

Despite the undeniable appeal of "The Skeleton Dance," Walt struggled to sell it and the Silly Symphonies series (a recurring theme in his life, at least in these early days). Eventually he connected with the right people in New York. When "The Skeleton Dance" premiered at the renowned Carthay Circle Theater, "the response was overwhelming" (Thomas). This led to the short being booked at the famous Roxy Theater, which proved the viability of the proposed musical series. Mickey Mouse was still the studio's main draw — years later, United Artists would only agree to distribute them on the condition that the title card feature "Mickey Mouse Presents" — but Walt knew he had stumbled on something special.

The right thing at the right time

Eventually, the Silly Symphonies would go on to make history and win awards, proving they were more than the "stepsister to the enormously popular Mickey Mouse series" (Thomas). The pairing of high-quality, visually stunning art with expressive orchestral scores won over audiences at a time of great disruption and uncertainty. It was the right thing at the right time. Kothenschulte explains:

For a demanding film-viewing public, who, in 1929, mourned the loss of the visual language of the silent film and feared the sound film would bring about a relapse into theatrics, Disney and his Silly Symphonies seemed like salvation.

Adding to this, the Sillies appealed to both music and dance in a way that other animation studios didn't seem to understand. And this was a bit controversial! As Douglas Brode argues in his book "From Walt to Woodstock: How Disney Created Counterculture," the Silly Symphonies often included "ritual celebrations" that present "dance — offensive to Christian extremists — as essential to our national character."

It's funny to look back at Walt at this time and think about how oddly humble he seemed, especially given the trajectory of his life. He was always known for his dogged determination, and a tendency to micromanage — borderline despotic, according to some accounts. Yet, even in 1929, after the success of "Steamboat Willie" and "The Skeleton Dance," there was still a grounded camaraderie about Walt Disney Productions.

In a 1929 interview with Florabel Muir, from New York Sunday News, Walt tells her not to ask about profits, saying that his brother Roy worried about that. Walt stayed modest and practical:

"Everybody here has his shoulders to the wheel ... Maybe sometime we'll all be rolling in wealth and move into more pretentious quarters and put on the high hat, but we won't be making any better movies."

To be fair, there was a certain person preventing Walt from making more money in 1929 — and his name was Pat A. Powers.

Walt Disney's Power(s) struggle

Back in Part 4, I alluded to Walt Disney signing a deal with the devil when he joined forces with Cinephone licensor Pat A. Powers. The Irishman didn't support "The Skeleton Dance" — he wanted Walt to focus on producing Mickey Mouse shorts — but that was far from the biggest concern with their partnership.

Walt was vulnerable when he went to New York City in 1928. He was a midwesterner at heart, and detested the urban pace of the Big Apple. To make matters worse, the businessman was completely out of his element trying to arrange sound recording for "Steamboat Willie." He had literally no experience in the field, didn't know how any of it worked, and was completely at the mercy of whoever wanted to work with him — a prospect people weren't exactly clamouring over each other to do.

Then he found Powers, who must have seemed like a guardian angel. He was anything but.

By the time he crossed paths with Walt Disney, Powers already had a duplicitous reputation. He'd gotten into the film industry through bootlegging cameras, tried to take Universal Studios from owner and founder Carl Laemmle, and then started an audio recording system for the film industry, Cinephone, that was based on ripping off patented technology. Disney, however, wasn't around for any of this Hollywood drama, and he saw Powers as a "good-natured cuss" and mentor. There were red flags from the beginning, ones that Walt willfully ignored. For example, the two initially signed a deal with Powers taking just a $50 fee for providing expertise during the recording session for "Steamboat Willie," but as the date approached, the terms shifted from a flat-fee to a $1-per-foot royalty that required Walt to provide a $500 deposit cheque.

The true cost of Cinephone

"Steamboat Willie" was a success (thanks in part to one Harry Reichenbach, a show-biz veteran who taught Walt that studio executives "don't know what's good until the public tells them"), and Powers found a way to enmesh himself with Walt Disney as much as possible. He told Walt that he wanted to promote Cinephone and that the Mickey cartoons would help him do that, then generously offered to "help." Powers would loan the money upfront for producing the cartoons and would handle the distribution, all for just 10% of the gross profits. Walt agreed to what he thought were good terms, and signed a contract.

However, Walt's trust in Powers was misplaced. The contract was far from favorable — something Roy Disney was furious to discover after the fact. (According to Thomas, Roy was annoyed his baby brother was so taken by someone he viewed as an obvious "crook.") Not only was Walt locked into a ten-year deal with Cinephone, but in addition to the 10% distribution fee, the studio was obligated to pay a $.25/foot of film royalty, and $13,000 a year licensing fee for the rights to Cinephone for ten years, regardless of if they used it or if it became obsolete in that time (per Gabler — Thomas says $26,000, but that seems too high). Disney also had to pay a $5,000 signing fee upfront.

Always the go-getter (and unafraid to ask friends and family for personal loans), Walt did manage to scrape together the money necessary to forge ahead with Cinephone. With Powers as a financier and distributor, Disney began producing the Mickey Mouse cartoons and then the Silly Symphonies. Tensions would arise between the two parties, thanks to Powers' crooked ways. Following the success of not just the Mickey Mouse cartoons, but also Sillies like "The Skeleton Dance," "Hell's Bells," and "Springtime" (described by The Film Daily in 1929 as "a corker"), the Disneys expected to have much more money coming in than they were getting, and Powers refused to show any sort of accounting documentation. He was pulling a similar stunt with them that he had with Universal, and the brothers (Roy especially) were having none of it.

Ub Iwerks, father of Mickey Mouse, leaves Disney (for now)

Getting rid of Powers would prove costly, and was only possible because Columbia Pictures intervened (the studio would take over distribution after Powers). Unfortunately, the 10-year Cinephone licensing agreement would continue (Roy eventually negotiated that down to $8,500 a year), and what's worse, Powers' actions had cost Walt two of his key employees and hometown friends: Ub Iwerks and Carl W. Stalling.

Despite their long collaboration, Iwerks parted ways from the Disney Brothers in early 1930, with Stalling following shortly thereafter. Both felt that their contributions were not being recognized adequately, and without getting into all the details, let's just say their grievances were at least somewhat justified. Iwerks and Powers teamed up to form an animation studio, but, obviously, it failed to give Walt Disney Productions a serious run for their money. (This was likely a power play intended to manipulate Disney into renewing his contract with, or even selling his company to, Powers. It was a miscalculation, to say the least.)

Even without his best animator and main composer, Walt prevailed. As his studio garnered notoriety, he steadily built of a talented team, and he maintained his steadfast dedication to quality above all else. In total, the series would run for 75 shorts, released between 1929 and 1939 — ending in time for the studio to shift to feature-length animated films. This would begin with the smash hit "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" in 1937, followed by "Pinocchio" and "Fantasia" in 1940. These animated features were unimaginably expensive to produce by the day's standard, and not all of them turned a profit. Today, they're all considered masterpieces, and they were only possibly because of the animation experimentation and general expansion happening at the studio in the '30s with the Silly Symphonies.

A technicolor marvel: Flowers and Trees

Walt Disney Productions really came into its own in the '30s. Yes, ol' reliable Iwerks — the one person who stuck with Walt when Charles Mintz took over the Oswalds — had left, and that surely stung, both personally and professionally. Fortunately, Walt Disney Productions was in a position to recruit top talent from New York, at a time when people would be willing to jump ship. That's how David Hand, a former animator for Max Fleischer's Out of the Inkwell series, ended up on the team. Les Clark, another Kansas City native who had essentially apprenticed under Iwerks, also stepped up at this time, taking over as lead animator after his former mentor quit.

Hand and Clark (and a guy named Tom Palmer) would animate the 1932 Silly Symphony "Flowers and Trees," which holds the distinction of being the very first Disney cartoon in vivid technicolor. According to Thomas, Walt really felt that the Sillies needed something extra to get out of Mickey's shadow, and just as he saw sound as the solution for "Steamboat Willie," he saw color as the future of the Sillies. Now, contrary to popular misconception, there was technology to make color movies before the '30s — it just wasn't practical, so it wasn't widely adopted. Technicolor Inc. created its first color film process in the 1910s, and steadily improved on its product until it developed its vivid three-strip camera in the early '30s. Disney pounced on the brand-new tech, despite the increased costs (it was the Great Depression after all).

The animation for "Flowers and Trees" was reportedly 60% done when Walt demanded the animators start over with color. This required a bit of trial and error. There were complications with introducing colored ink — the main one being that the high heat of the camera and lights caused ink to crack. It was also expensive to produce. Luckily, the gamble more than paid off: "Flowers and Trees" was a hit, winning the first ever Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. What's more, because he was an early adopter, Disney negotiated short-term exclusivity rights for animation, meaning his competitors couldn't use the Technicolor technology for two whole years.

Three Little Pigs blows the house down

Following the critical and commercial success of "Flowers and Trees," Walt decreed that all Sillies should henceforth be in vivid technicolor. The Mickey Mouse shorts were popular enough that they stayed in black and white (which was less costly to produce) for the time being. "Flowers and Trees" was also the first film to be released by United Artists (Disney and Columbia had a falling out), and one of the last few to be recorded with Cinephone. By December 1932, Walt Disney Productions had transitioned into using RCA Photophone.

In April 1933, the Sillies had another major hit: "The Three Little Pigs." This short was based on the children's fable, and was a sensation. It introduced the song "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf." (The song was such a hit it went on to have a life of its own, which includes being covered by LL Cool J in 1991.) It would also take home an Academy Award, and today is regarded as one of the greatest cartoons of all time. If you grew up watching "The Wonderful World of Disney" on ABC, you've probably seen the short at least once.

So why was this short such a phenomenon? Obviously, it had the color and sound going for it; however, one of the bigger innovations was that Disney placed a lot of emphasis on developing the story and the characters. This was about the time Walt began experimenting with a dedicated story department. The pigs and the wolf have very clear and distinct personalities and motivations, and this makes the story more compelling than say, the nondescript dancing plants in "Flowers and Trees."

The story also reflected the public's feelings at the time. In "Cartoons in Hard Times," Tracey Louise Mollet argues that the "narrative and characters of the animated short ... embrace the values of the new administration" — referring to the Roosevelt administration and The New Deal. (If you're not up on your Depression-era history, essentially FDR introduced a bunch of federal legislation to bolster the American economy and help those struggling, which was basically everyone.) Mollet further posits that the "carefree" pigs represent the attitude of the '20s, while the hardworking, "practical" brick-house-building pig is the New Deal. In this analogy, the wolf is uh ... unchecked rampant capitalism, I guess? Point is, Disney had his finger on the pulse of America for this one.

Disney producing anticapitalist propaganda (really)

In all seriousness, this same argument appears again in Brode's book. In the chapter "Little Boxes Made of Ticky-Tacky: Disney and the Culture of Conformity," he also argues that "The Three Little Pigs" is an allegory for The New Deal. What's more, he sees the trend of Silly Symphonies taking established moral tales and softening them as part of an ideological push for fellowship in difficult times:

Some critics accused Disney of sentimentalizing ["The Three Little Pigs"] by having the two silly pigs survive ... An alternative reading takes the film as a call for community. Together, the three pigs defeat their common enemy, even as Americans might conquer the Big Bad Wolf of the Depression. Such a concept recurs in "The Grasshopper and the Ants." ... Rather than allow the Grasshopper to die of cold and starvation, his Ant Queen instructs her minions to drag him inside their hall. Had Disney stuck to the source, his film would play as socially Darwinistic. Instead, we see a democratization of the myth.

Brode goes on to discuss the short's liberal, progressive message with its feminist portrayal of a benevolent Ant Queen. Walt's apparent defense of socialism (or at least socialist ideas) would continue and eventually inform "Snow White" — in particular, his characterization of the Seven Dwarfs as hard workers whose pleasure is derived from the work itself rather than the rewards. There are countless "Disney moments" that fit this mold: Sorcerer Mickey learning responsibility in "Fantasia," the glorification of performance work in "Dumbo," and heroes doing chores in "Cinderella" and "Mary Poppins."

The Silly Symphonies would peak with "The Three Little Pigs," but as the series continued throughout the decade, one can observe Walt fine-tuning his approach to adapting fairy tales and fables to animation. We see the origins of the Seven Dwarfs in the frolicking "The Merry Dwarfs," the adorable Figaro kitten from "Pinocchio" and later Berlioz, Marie, and Toulouse from "The Aristocats" in "Three Orphan Kittens" — even "The Little Mermaid" seems to draw from the underwater festivities in "Merbabies." Watching the Sillies now in 2023, it's easy to forget just how old they are, largely because they are just that good, and just that revolutionary. And the influence is not just on later Disney productions either — these "animated ballets" led to Warner Brothers' Merry Melodies series, which gave us Bugs Bunny and pals. Hell, even Tex Avery's horny wolf in "Red Hot Riding Hood" bears a striking resemblance to the antagonist from Disney's "Three Little Pigs."

'The Silly Symphonies were Walt Disney's 'Arcadia'

Kothenschulte writes:

More than the Mickey Mouse series, which was the cornerstone of Disney's worldwide success, the 75 short cartoons in the Silly Symphonies series are the benchmark of ... artistic and technical perfection. And yet it would be an understatement to merely admire them as milestones along the way to later masterpieces.

Just as we see early silent film history today as far more than just the infancy of cinema, but rather as a time of inexhaustible fantasy and variety, never to be repeated again, the Silly Symphonies were Walt Disney's arcadia.

So why aren't the Silly Symphonies a bigger part of The Disney Company's public image today?

I have a theory: the Silly Symphony approach — described in the aforementioned making of featurette as "an animated ballet" — was not conducive to branding. Sure, many were marketed with "Mickey Mouse presents" in the title cards, but that's where the connection to the core series ends. The characters and stories were all independent, and none really broke out to becomes iconic in their own right. When was the last time you saw the Cookie Carnival guy on a T-shirt? (He's charmingly named "Hobo Cookie" and he gives another cookie an icing makeover so she can win a beauty contest. This short is so deliciously weird).

Also, because the Silly Symphonies featured new characters and stories each time around, there's not much to connect them together, other than a general aesthetic that today's audiences probably wouldn't pick up on. The 1929 short "Hell's Bells" is cool, but it's not that different from the 1934 Betty Boop short "Red Hot Mama" — and the latter benefits from having an instantly recognizable character at its core. This may be why the Walt Disney Company hasn't been able to use the Silly Symphonies more as branding tool. For example, the name today is probably most known among the general public for the Silly Symphony Swings ride at Disneyland, and the theming of that attraction is actually a Mickey Mouse cartoon, "The Band Concert," rather than an actual Silly Symphony film. The time period is right, but the content isn't.

The legacy of the Silly Symphonies

The way people consume media has changed drastically since the inception of the Walt Disney Company. When the Silly Symphonies were in production during the '30s, they were shown as introductory cartoons before a feature film in a movie theater. This was a time when films would inevitably be dropped from the schedule, and no longer be accessible. Occasionally, films could get re-released if they were particularly noteworthy — this is how "Fantasia" eventually became profitable — but generally speaking, one's ability to see a movie was limited to the time it was in theaters, and this was especially true of cartoons like the Sillies.

I am so grateful to be living in an age when I can access 100 years' worth of brilliant animation with just the press of a button. But this is new. The tragic fate of the Silly Symphonies — magnificent pieces of artistry that were once culturally dominant and are now so obscure that their own company doesn't promote them — is the result of an attitude of ephemeral enjoyment, made worse by Disney's history of a covetous "vault" approach to its media.

Kothenschulte explores this problem in his conclusion, discussing why the Sillies didn't produce more icons despite their wide appeal:

Each of these characters continue to appeal to audiences as they did in the 1930s. And yet, until the release of two DVD sets hosted by Leonard Maltin in 2001 and 2006, respectively, the majority of these characters managed to remain invisible for decades. Only the Oscar-winning films were rereleased in theaters as an "Academy Award Review of Walt Disney Cartoons" in 1937 and 1966 and, in some cases, were marketed as 8 mm home movies.

If you've made it this far in my overly long article, please do yourself a favor: go to YouTube and watch these shorts.

Join us next week for 100 Years of Disney Magic Part 6, where we'll dive into Disney's ambitious, history-making animated feature film, "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs."