Scream 2 Ending Explained: The Killers Were Never Going To Be Hallie And Derek

Although "Scream 2" was mostly well-received back in 1997, audiences had one major complaint: the killer reveals were far more underwhelming than they were the first time around. Some of this was unavoidable; the first film's big twist was less the killers themselves than the fact that there were two of them, so it could afford to make both Billy Loomis and Stu seem sketchy as hell without giving too much away.

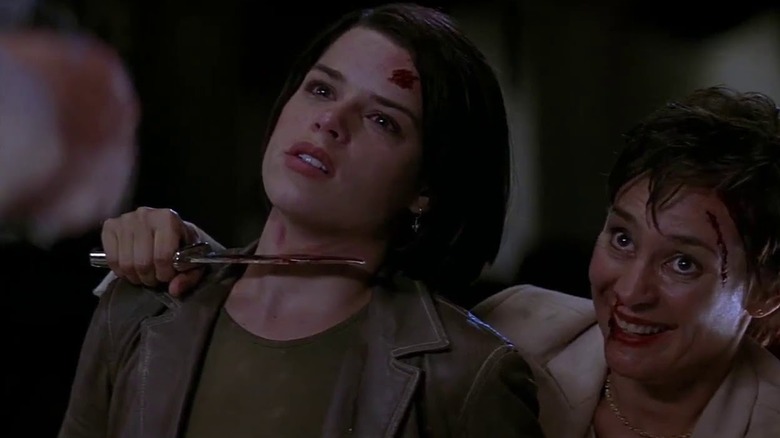

"Scream 2" didn't have that luxury. The possibility of two killers had not been forgotten, so screenwriter Kevin Williamson had to come up with a different approach for its two big reveals. The result was a little disappointing; the killers turned out to be Mickey (Timothy Olyphant) and Debbie Salt, aka Mrs. Loomis (Laurie Metcalf) — two characters who didn't make a huge impression on audiences pre-reveal.

Upon rewatch, it's clear that Mrs. Loomis was indeed a constant presence throughout the film, showing up often enough to make her reveal feel earned, but Mickey? He was barely in the second half of the movie at all, and his scenes in the first half were few and far between. Add on the fact that Mickey and Debbie Salt never interacted pre-reveal (making it pretty much impossible for any viewers to guess their partnership), it makes sense that the urban legend of rewrites about the killer has been taken as truth in recent years.

What is this urban legend, you ask?

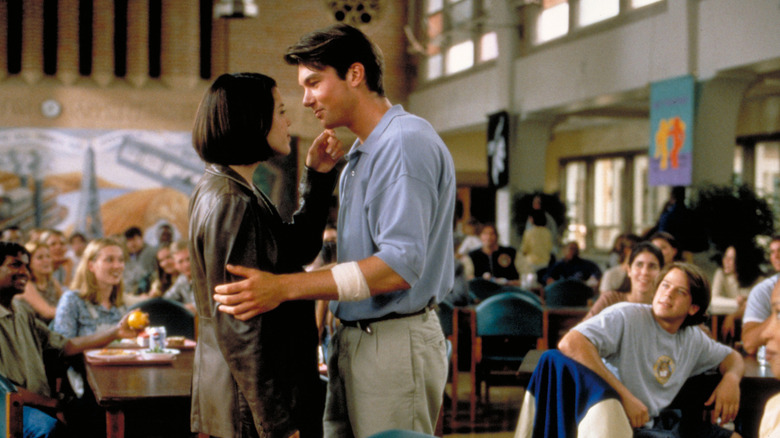

The big, behind-the-scenes story that still gets passed around is that the script originally had Hallie (Elise Neal) and Derek (Jerry O'Connell) as the two killers, but after the script was leaked online, the writers rewrote it to maintain the element of surprise. It's an eye-catching piece of false trivia, as Hallie and Derek would've made for a way more shocking reveal than what we got. They both got a significant amount of screentime pre-reveal, so their betrayals would've stung so much worse than the betrayals of Mickey and Mrs. Loomis, neither of whom ever seemed particularly close to either Sidney or Gale.

In reality, Mickey and Debbie were the intended Ghostfaces from the very beginning. The script with Hallie and Derek as the killers was simply one of many decoy scripts that were released to keep viewers off the trail. This myth still persists, however, and it's easy to see why: the idea that the writers changed up the killers' identities at the last minute makes sense because that's certainly how it feels. At least, that's how it felt on the first watch.

But upon closer inspection, it's clear that a Hallie/Derek reveal would've been terrible. Sure, it would've been shocking, but it also would've ruined so much of the thematic ground this movie was exploring. Mickey and Debbie's reveals might've seemed random and arbitrary, but in the end, they were far better choices for Ghostface than any of the other characters.

Why Mickey worked

Although Mickey should've been in the film more than he was, you must admit that the writers made the most of him for the scenes he was in. His flashiest scene was the film class debate about violence in film and the legitimacy of sequels, in which he laid out his Ghostface motivations ahead of time. He argued that movies do in fact cause real-life violence, already setting the groundwork for the eventual trial he planned to have, and he argued that sequels could be better than the original: an argument that was exactly what you'd expect from a killer trying to make a real-life sequel.

But where Mickey really stood out was with the quiet, subtle way he sowed doubt into Sidney's mind. After Derek got stabbed off-screen after running into the empty sorority's house, Mickey casually wondered aloud to Sidney, "Why would anyone go back in that house anyway?" On first watch, it didn't even seem like he was suspicious of Derek; when Sidney's eyes widened with suspicion towards Derek at the comment, it felt like she was putting the pieces together that Mickey had accidentally set up for her. It's only upon rewatching that it becomes clear that this wasn't Sidney being intuitive; it was Mickey psychologically torturing her without her picking up on it.

This was Mickey's main appeal as the killer: he was a character who understood exactly what Sidney's weaknesses were and he used this knowledge to mess with her head in a way that none of the other suspects could. It wasn't enough for Mickey to kill Sidney's boyfriend; he had to make Sidney doubt Derek first, turning her into an unwilling participant in his murder. Grief wasn't enough for Mickey. He wanted Sidney to feel guilt.

Why Derek and Hallie wouldn't have worked

The tragedy of Sidney's arc in "Scream 2" was that the lessons she learned from the first film were exactly what she needed to unlearn in the second. In "Scream," she made the mistake of trusting her boyfriend. Here, she made the mistake of not trusting him. She'd even keep her best friend Hallie at arm's length. "What am I supposed to do, just cut everybody off? Crawl under a rock?" she asked Dewey early on, and this was the big central question behind nearly all of her scenes. Both Hallie and Derek kept insisting she keep them in her life, for her to not close herself off forever, and part of Sidney wanted to listen.

But for Derek especially, those pleas for her to let him be there for her were severely undercut by the constant sneaking suspicion that he was secretly a killer. Every nice thing he did in this film, every big romantic gesture, was tainted by Sidney's self-doubt. After all, she was wrong to trust her boyfriend before. Why wouldn't she be wrong again?

The irony was that by the end of the film, it's made clear that Sidney had gotten way better at picking trustworthy people to keep in her life. Having Derek as her boyfriend and Hallie as her best friend showed good judgment. It was good judgment that Sidney wrongly started to doubt, only for her initial positive impressions of the two to be proven right in the meanest way possible.

The movie always agreed with Derek and Hallie

By the start of "Scream 3," Sidney had gone and done exactly what she was talking about with Dewey. She cut herself off entirely, except now she was doing it less out of concern that her loved ones were secretly out to get her, and more from concern that she was putting her loved ones in danger by being around them. Derek's death was what sealed the deal. There was relief in knowing that her original trust in him was right, but the guilt and grief overrode all of it.

That's why Derek's necklace became a motif throughout the later movies: the necklace served as Sidney's reminder to open herself up to other people, regardless of how much pain it might one day bring her. "Scream 3" was the movie where Sidney learned to embrace the advice Derek and Hallie gave her, which is why she only wore the necklace after she decided to go to Los Angeles. "Scream 2" was all about establishing what Sidney needed to do to find happiness, but hurting her so much that such a feat became seemingly impossible.

Although Derek and Hallie died in "Scream 2," so much of what they said to Sidney stuck with her throughout the rest of the series. If "Scream 2" had made them the killers, all of that would've been undermined. Her trust issues would've been entirely vindicated, and the road to Sidney finally finding closure in "Scream 3" would've been much harder to believe.

So now that we've established Mickey was a suitable choice for a killer, and that Derek and Hallie weren't, how did Mrs. Loomis fit into things?

Why Mrs. Loomis worked

There's the easy answer to this question: Laurie Metcalf was amazing in the role and we shouldn't need to think up a reason to let her ham it up like a old-school Disney villain. But there's also the longer explanation: Mrs. Loomis was necessary because she made things personal for Gale (Courteney Cox).

Although Gale's multi-faceted personality was slowly unveiled throughout the first film, it was only in "Scream 2" that she changed as a person. She went from a power-hungry, insensitive reporter to someone genuinely interested in getting justice and protecting her friends. It's easy to miss, but most of this change was the result of Mrs. Loomis' actions in particular. Loomis killed Randy, after all; it wasn't part of her plan, but when Randy insulted her son, she got, as she'd later put it, "a little knife happy."

Randy's death was the first time Gale faced a significant loss in this series, and it was the moment Gale finally stopped looking at the situation through the lens of her own career. There was also the fact that, because Gale was so dismissive of Loomis' reporter alter-ego throughout the movie, Mrs. Loomis had a grudge against her specifically. Mickey (much like Billy and Stu) didn't seem to have any strong feelings towards Gale, but Mrs. Loomis' Ghostface chased after Gale with surprising ferocity. Basically, Loomis treated Gale like all the other Ghostfaces treated Sidney.

This was how "Scream 2" firmly established Gale as a co-protagonist of the series, as the other final girl. In order for that to work, she needed to have a much stronger connection with one of the killers than she did the first time around, and Debbie was the only option. (Well, it was either her or Gale's cameraman, Joel.)

Why Cotton couldn't be the killer

This leaves us with the last major suspect as "Scream 2" entered its final act: Cotton Weary (Leiv Shreiber), the man who Sidney accused of murdering her mother before the events of the first movie. It was only in this film that we got to see him in the flesh, interacting with Sidney face to face, and it was riveting.

Even back in "Scream," the mere existence of Cotton was a fascinating part of the story. The writers could've easily kept Maureen Prescott's murder unsolved, but they chose to establish that Sidney wrongly sent an innocent man to prison for murder. It didn't make Sidney a bad person, obviously — she was grieving, and Cotton was framed — but it was still a massive complication. In the first film, this complication just served to flesh out Gale's character, proving she was right about some things despite her questionable reporting ethics, but it was only in "Scream 2" that this storyline yielded some truly fascinating results.

Cotton was never a bad guy, exactly, but he was not a clear-cut good guy either. He didn't murder Sidney's mother, but he was still having an affair with a married woman. Although he seemed obsessive and creepy in his confrontation with Sidney in the library halfway through this movie, most of what he said was justified. If you were falsely imprisoned for a year and still treated with suspicion afterward, you'd probably insist on that Diane Sawyer interview too. The result was that Cotton only got a small handful of scenes in "Scream 2" before the final showdown — less than Mickey or Mrs. Loomis, technically — but he made far more of an impression as a suspect. So, why didn't they go with him as the killer?

Taking the more complicated route

The obvious answer is that it would've been too obvious: Cotton's motivations for wanting to kill Sidney were too straightforward to be a satisfying reveal. The long answer is that Cotton's role in the final showdown was so compelling that the writers would've been fools to pass it up. Cotton ended up pointing a gun at Mrs. Loomis as she hid behind Sidney, her knife at her throat. Loomis urged him to let her kill Sidney, and in return, she'd let him get the spotlight as the sole survivor of this massacre. "She sent you to prison for a year!" she told him. "Personally, I think it's rather poetic."

Cotton ended up shooting Mrs. Loomis, of course, but not before making a coded bargain with Sidney. "That Diane Sawyer interview's looking real good right about now," he said to her. Loomis didn't get what he was referring to, but Sidney understood him perfectly: "Agree to go on Diane Sawyer with me, or I'll let you die."

So, Cotton got to have his hero moment where he saves Sidney, but it was done in a way where Sidney kept her agency and Cotton didn't come across as particularly heroic. It was never clear if he actually would've let her die if she'd refused — his actions in "Scream 3" implied he probably wouldn't have — but that ambiguity helped to make Cotton one of the most fascinating characters in the series. Even though we now know he wasn't Ghostface, he was still such a uniquely complicated, morally grey character, and his inclusion in this film's third act was one of the many elements that elevated it beyond that of a generic horror sequel.

Mickey got the worthy sequel he always wanted

The final moments of "Scream 2" were surprisingly upbeat. Dewey was revealed to be alive, and Gale's character arc concluded beautifully with the scene where she stopped reporting and chose to follow Dewey into the ambulance. While Dewey's survival was admittedly a little ridiculous (it's up there with Kirby in terms of improbable survival stories), it was hard to complain. This movie was filled with so much death and gore, to the point where the minor miracle of Dewey's survival felt more than earned.

Yet despite the uplifting music, this was not a happy ending for Sidney. Gale, Dewey, and Cotton might've been in a better place than when they started, but Sidney was last seen walking by herself into the distance. Sure, there was the relief in knowing that this recent round of killings was over, but now she was completely alone. This was the beginning of the self-imposed isolation we found her in at the start of "Scream 3." This was Sidney's low point in the franchise, where she fully lost all hope of ever being happy.

As someone like Mickey would put it, this was the "Empire Strikes Back" of the "Scream" franchise. This was the middle installment of a trilogy that expanded on and darkened the themes of the first installment, leaving the main character at their lowest so that their triumphant conclusion in the third installment could have more impact. Like the "Star Wars" franchise, the "Scream" franchise's first movie might've been a big surprise hit, but it was with the second film that we knew this was a franchise that would be sticking around for a long, long time.