Night Of The Living Dead Ending Explained: And Then There Were None

The threat of reanimated corpses hounding the living has been a consistently effective horror trope across cultures, first portrayed on the big screen in Victor Halperin's 1932 pre-Code horror feature, "White Zombie." Although Halperin's film does not exclusively adhere to the parameters of a quintessential zombie flick, it sets the foundation for a certain kind of monster that has shambled its way through the survival horror genre.

However, it was George A. Romero's unforgettable directorial debut, "Night of the Living Dead," that emerged as the blueprint for contemporary zombie horror, acting as a catalyst for countless stories that mimic Romero's 1968 original. Although Romero never used the term "zombie" — the film calls them "ghouls" instead — the undead in "Night of the Living Dead" follow the rules of reanimation and crave human flesh, setting the precedent for one of horror's most-utilized monster figures.

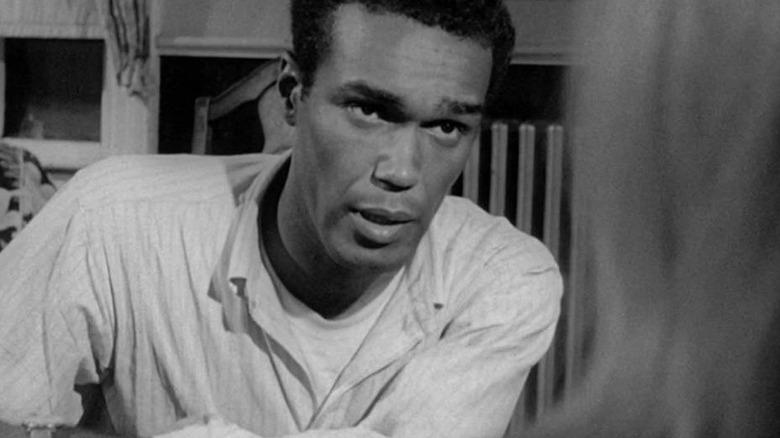

One of the reasons why Romero's splatter film still endures is due to the expert usage of ordinary settings to evoke deeply disturbing imagery, despite a shoestring budget and a cast comprised of acquaintances and amateur actors. The controversy surrounding the lack of an MPAA rating during the film's premiere extends into its gut-punch of an ending, where Ben (Duane Jones) is mistakenly (and cruelly) shot despite fulfilling the qualities of a final survivor. The death of Ben, a Black man who essentially stands out as a rational, resourceful lead in contrast to the spineless, overdramatic demeanor of the movie's other characters, grants an inescapable racial tint to Romero's zombie film. Even in a world overrun by a clearly distinguishable supernatural threat, Ben is shot down by police officers without hesitation. How does this ending fare 55 years later, and why is Romero's film still relevant?

Dwindling identity and the terror of alienation

Any kind of mutation in the human body immediately leads to the morphing of identity, which is directly linked to the question of what makes us human. George A. Romero's film, which was hugely inspired by Richard Matheson's horror novel "I Am Legend," switches out vampires for ghouls to explore these themes of identity-centered alienation in greater depth. Moreover, Romero depicts cannibalism as a core identifier of the undead status. These genetically mutated beings, who somehow defy the laws of nature, feed off the living, which helps create an unprecedented power structure. While everyone in the film reacts to this unsettling status quo with a startling lack of agency, Ben is the only person who fights back sensibly while exercising the skills to survive a hellishly hostile environment.

Barbra (Judith O'Dea), who functions as an entry point into Romero's bleak, perilous world, is chased by the shamblers to the point that she barely manages to escape. However, when she encounters Ben, she does not heave a sigh of relief. Instead, she discerns him with quiet suspicion and perturbation, even though he actively guides her to the safety of the farmhouse. While this barely covert, uneasy racial tension present between the two characters is meant to reflect the socio-political anxieties of the 1960s U.S., Ben's status as the definitive hero in Romero's film counts as a deliberate act of subversion.

Although the threat of the looming undead should ideally overpower everyday identity politics (and the discriminatory violence that comes with it), the group of human survivors still indulge in power struggles and mistrust one another. Thus, the terror of alienation and identity erasure is multifold, especially for Ben, who exemplifies the realities of being a Black citizen of the U.S.

Looking into the mirror, only to be repulsed

George A. Romero shot "Night of the Living Dead" with a specific brand of guerilla filmmaking techniques, which helped ground the film's layered terrors in realistic grittiness. This almost-documentary style "realness" is further reinforced with the use of human attempts to interpret the sudden zombie apocalypse. Scientists and experts weigh in on the impending doom, and posit that the root cause might be a radiation-based genetic mutation (triggered by an object from outer space). While the premise seems dystopian, the reason why the ghouls manage to terrify us with such urgency is that they look like us. The undead are ghosts of who we used to be, mutated beyond recognition. It is like looking into a mirror and being forced to confront our inherent monstrousness, which manifests in the structural injustices that plague us as a society.

Classic critical interpretations of the massacre at the heart of the film have drawn parallels to the insensible atrocities of war, and the inescapable bleakness that haunts the aftermath. Although a nuanced analysis of these potential threads requires ample time and introspection, "Night of the Living Dead" definitely utilizes nihilism in its favor. This is not your run-of-the-mill genre offering that ends with reinforced hope for the human race. Instead, the film hounds us with relentless images of death and carnage and robs us of the catharsis that would have accompanied Ben's survival.

There is no hope for normalcy, no cure, no surviving figure to emerge victorious. Instead, the lone survivor is targeted as the other and promptly shot down by traditional enforcers of law and order. However, despite Ben's death, his character is the first Black lead in the horror genre, and this legacy carries significant weight in our collective cultural memories.

Layers of subversion make an indelible impact

When Barbra and her brother are first introduced, George A. Romero sets up the stage for her to assume the potential mantle of the final girl. Within minutes, she experiences familial loss and falls victim to the undead who are out to get her. Although Barbra is prone to futile theatrics that do not help her chances for survival, there is little to no reason to believe that she will not make it to the end. This is when Romero uses subversion: Ben suddenly enters the scene, offers no explanation for his presence, and immediately commands the situation, along with our attention, in the midst of the crisis. As more characters are introduced in the mix, Ben consistently justifies his final survivor status by demonstrating guts and pragmatism, and is unafraid to call out the bigoted behavior of the white survivors.

At the forefront of overt racism is Harry (Karl Hardman), who wishes to assert dominance and dethrone Ben as the default leader of the group. This antagonism is clearly racially charged, as Harry exudes a twisted sense of entitlement even amidst a life-threatening, end-of-the-world scenario. The younger couple in the scenario takes a less-biased stance, as they support Ben's leadership based on his abilities, and attempt to defuse tense situations between Harry and Ben repeatedly. In the end, Harry's refusal to trust Ben leads to his undoing."The cellar is a death trap," Ben warns, but Harry deems it an impenetrable fortress. It is obviously anything but.

While Ben emerges as the rare instance of a Black survivor at the forefront of an apocalypse, his death remains a chilling reminder of the ugliness of race-based dehumanization. Piled alongside a mound of undead, Ben's body burns, a frightening final image that is forever haunting.