Star Trek's Spock Was Always At His Best When He Was A Little Less Human

The original "Star Trek" pilot, "The Cage," did a wonderful job of establishing the tone of the series, and the types of strange, psychological crises that the characters on it would regularly encounter. Jeffrey Hunter played the short-tempered and serious Capt. Pike, and Majel Barrett played his first officer, only referred to as Number One. It wouldn't be until "Star Trek: Strange New Worlds" in 2022 that Number One's name, Una Chin-Riley, would be mentioned on screen. The original pilot for "Star Trek" was ultimately rejected, and most of the show's original elements were retooled. It wasn't until the second pilot, "Where No Man Has Gone Before," that the best-known 1966 Trek ensemble would be established. The only things that were carried over were the technology, the Starfleet symbols, the name of the U.S.S. Enterprise, and the character of Spock (Leonard Nimoy).

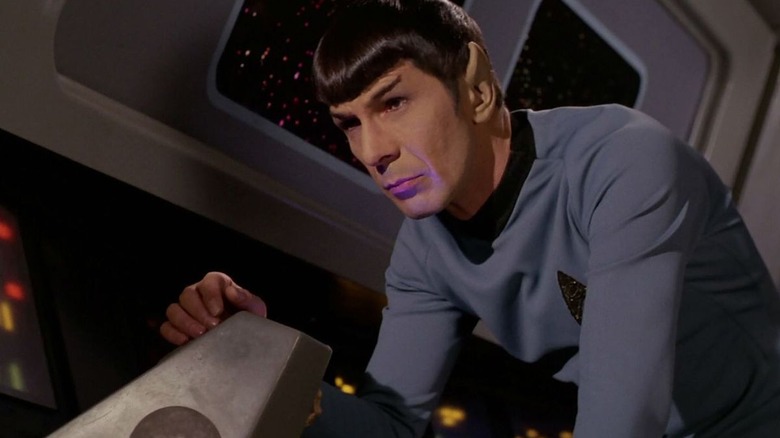

Spock, a half-human, half-Vulcan science officer, was the most striking, eye-catching character on the young show. Sporting pointed ears and angled eyebrows, he was just alien enough to get viewers' attention. He also behaved strangely. In the lore of "Star Trek," Vulcans have rejected the cultivation of their emotion, choosing instead to focus on the all-encompassing power of scientific logic. As such, Spock often spoke coldly, rejecting the impassioned ravings of his human co-workers, and striking a good balance with the frequently angry Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) and the instinctual, level-headed Capt. Kirk (William Shatner). A common interpretation of the three credited leads of "Star Trek" is that of mind (Spock), body (McCoy), and soul (Kirk). Or, for the Freudians, id, ego, and superego.

Whatever the interpretation, though, Spock is a vital linchpin in the series' popularity. One might fairly call him the most important character in "Star Trek."

Don't knock the Spock

There might be some debate, however, as to what Spock's central appeal is. In speaking to other Trekkies, I've encountered several people who prefer Spock as he behaved in the episode "Amok Time" (September 15, 1967), the first episode of the show's second season. In "Amok Time," Spock revealed that his species experiences a peculiar seven-year itch called pon farr, an instinctual mating drive that transformed otherwise staid Vulcans into angry, horny monsters. The climax of the episode will see Spock fighting Kirk to the death over who gets to mate with the Vulcan T'Pring (Arlene Martel). When Kirk cleverly eludes murder, Spock is elated to see him alive. He even smiles. "Amok Time" saw the stalwart Spock feel rage, lust, embarrassment, joy ... the whole gamut of emotions.

Fans of "Amok Time" like to point out that Spock, in being half-human, is just as prone to impulses and passions as the very human audience watching him. They might find comfort in the fact that even a weird, emotionless alien is relatable and vulnerable. Some enjoy watching their powerful heroes humanized, and that's what "Amok Time" does.

Personally, the above-stated appeal of "Amok Time" has never sat well with me. While I can appreciate Spock's rage from a storytelling perspective and enjoy the expansion of Vulcan society within the Trek mythos at large, I took no pleasure in watching Spock break into a fit of rage or an uncontrolled smile. For many, Spock's power came from his stalwart inability to crack. Indeed, the counterargument could be made that Spock's central appeal is not his humanity, but his Vulcan-ness. It's when Spock is faced with an extreme scenario and doesn't succumb to emotional pressure that he becomes more interesting and admirable.

Spock's command skills

One might look to the episode "The Galileo Seven" (January 5, 1967) as a counterpoint to "Amok Time." In that episode, Spock and several other human crewmates were forced to crash their shuttlecraft, the Galileo, on an unvisited planet called Taurus II. The local inhabitants are a species of 10-foot cavemen that kill a few of the crewmembers with spears and begin smashing boulders into the shuttle. Spock, the commanding officer, attempts to logic his way out of a desperate situation, with imperfect results. He, however, doesn't give in to bloodlust, revenge, or panic like the people around him. He stays in character, even when the situation might have inspired a more emotional response, and is all the more admirable for remaining who he is and relying on his strengths.

"The Galileo Seven" also reveals that Spock may not be the best commanding officer. If one seeks humanizing flaws, one can easily point out that Spock falters when outside of his scientific, analytical wheelhouse.

Spock's inability to "break" might serve as the blueprint for the general professionalism that remains pervasive throughout the franchise. "Star Trek" is, we here remind ourselves, a workplace drama foremost, featuring uniformed characters who are on the clock. A general thrust of "Star Trek" is that everyone has a job they're devoted to, and they try to do as well as they can. "Star Trek" is aspirational in that regard, depicting a multicultural workplace where everyone's strengths are respected. Spock was the acme of Starfleet probity. He kept calm, even as the job became stressful.

Except for that time he was played by Zachary Quinto and wailed on a guy's face with his fists.

The passionate Vulcan

The ethos of J.J. Abrams' rebooted "Star Trek" film series (2009 – 2016) was that the crew — in a parallel universe — were younger and more impulsive than previously seen and hence more prone to youthful emotional outbursts. As such, Spock (Quinto) was sexually passionate with Uhura (Zoe Saldaña) and, in "Star Trek Into Darkness," given to wrath. When Khan (Benedict Cumberbatch) attacked the Enterprise and caused Kirk (Chris Pine) to die, Spock flew into a rage, chased down his attacker, and pounded his face repeatedly on the roof of a speeding space-van. In terms of action movie shlock, I suppose this is typical for the genre. In terms of "what Spock would do," it felt very, very wrong. Perhaps fans of "Amok Time" enjoyed watching Spock become a violent a-hole. Others, meanwhile, remembered that Spock was once known for logic and diplomacy and had trouble connecting extant Trek knowledge with the hockey goon on screen.

Watch "Into Darkness" and the "Star Trek: The Next Generation" two-parter "Unification" (November 4 and 11, 1991) back-to-back sometime, and experience the most violent form of pop culture whiplash since "Highlander 2: The Quickening." In "Unification," Spock (Nimoy) is as logical as he has always been, and speaks openly about the hard work required to achieve justice and force society to grow. Not once does he beat a guy's face in on the top of a van.

The latest iteration of Spock, as played by Ethan Peck on "Star Trek: Discovery" and "Star Trek: Strange New Worlds" is striking something of a fair balance between Amok Spock and Galileo Spock.

New Spock

On the one hand, the character is finally allowed back into a professional setting, having to behave professionally among his fellow crewmates. On the other hand, T'Pring (Gia Sandhu) now plays a larger role in his life, and the two of them are openly sexually attracted to one another. They speak in cold terms, but their twinkly eyes and frequently nude bodies speak to other interests. Peck plays Spock with a mild smirk, giving the character a human, bemused quality, even as he speaks coldly and behaves logically. This blend is appealing to many fans of the show.

To reiterate, however, Spock is always going to be more appealing the more logical, the more alien, and the more Vulcan he is. There are viewers who look to Spock as an aspirational figure. Indeed, those who are on the autism spectrum or who are merely socially awkward can hold Spock up as a character who is refreshingly free of bothersome traditional social interactivity. Essays by people wiser than myself have been written about Spock's status as an autistic character, and how he might serve as a positive representation of neurodivergence. The fact that he operated by his own scientific code and regularly rejected (or was befuddled by) the dangerous emotional whims of people around him made him inspiring. He was emotionless, yes, but was never anything less than heroic, intelligent, and a vital member of the crew.

Indeed, it was when he did show emotions that the ship was in trouble. Emotional Spock was a sign of danger. A signal that something had broken. When Spock has everything under control — and he very often had everything under control — we knew we were safe and that everything was right with the universe.