Tales From The Box Office: Chicago Did A Killer Job Of Making Musicals Cool Again

(Welcome to Tales from the Box Office, our column that examines box office miracles, disasters, and everything in between, as well as what we can learn from them.)

Musicals have been an absolute staple of Hollywood pretty much ever since people started selling tickets to watch moving pictures on a large screen. But, like every other tried and true genre in filmmaking, it has had its ups and downs. There was, at one point, a tremendously long down period for musicals, roughly from the '70s up through the early 2000s, where several other trends dominated multiplexes, leaving song and dance pictures largely out in the cold.

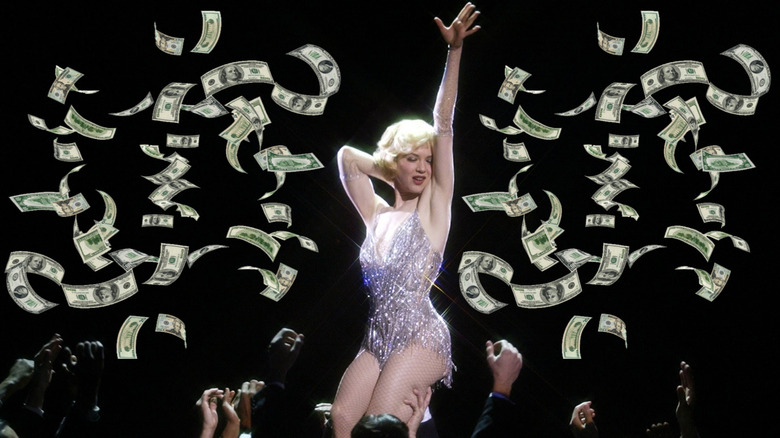

Be that as it may, everything seems to come back around again eventually. For musicals, that happened 20 years ago when Rob Marshall made his feature directorial debut. Marshall is the man who brought the long-running stage musical "Chicago" to the big screen, and it was arguably one of the most successful first movies ever. The adaptation would go on to make a boat load of cash at the box office and, to top it all off, have a fairytale night at the Academy Awards.

In honor of the movie's 20th anniversary this past week, we're looking back at "Chicago," how Marshall convinced Miramax to let him make it, how it became the kind of hit we don't see all that often anymore, and what lessons we can learn from it in the modern context. Let's dig in, shall we?

The movie: Chicago

"Chicago" was originally a musical by Bob Fosse and Fred Ebb that was wildly successful, but it was actually based on a prior play from 1926 by Maurine Dallas Watkins. Eventually, Hollywood decided it would be a good idea to make the successful stage musical into a feature film. It landed at Miramax which, at the time, was an absolute powerhouse, particularly with films that had the chance to be both critical darlings and box office draws. This was long before the ugliness of Harvey Weinstein would be exposed to the world, dismantling the empire he had built.

The movie focuses on Roxie Hart and Velma Kelly, two dancers who find themselves on death row and develop a fierce rivalry with one another. Each having committed murder, they find themselves in competition for publicity, fame, and the attention of a sleazy lawyer. Throw a bunch of showstopping musical numbers in the mix and it's easy to see how this could be a compelling, entertaining romp. Ultimately, it was Rob Marshall who would find himself in the director's chair — though, had things gone another way, he could have directed Disney's "Enchanted" instead.

Marshall was originally brought in to discuss the prospect of bringing the hit musical "Rent" to the big screen. He instead hijacked the meeting and explained how "Chicago" could be done as a movie. It worked. From there, it was his to develop, with screenwriter Bill Condon coming aboard. There weren't even any stars attached yet, though eventually the strength of what the team developed garnered a deeply impressive cast, led by Catherine Zeta-Jones, Richard Gere, and Renee Zellweger. The supporting cast, which includes John C. Reilly, Lucy Liu, and Queen Latifah, is no slouch either. Marshall had, effectively, talked his way into a situation even seasoned filmmakers could only dream of.

The only problem? Musicals were dead as a doornail.

Movie musicals were dead in the early 2000s

It is so incredibly important to emphasize just how not in vogue musicals were at the time. Just to help illustrate that point, the last time a musical had won Best Picture at the Oscars before this movie came around? It was in 1968 with "Oliver!" taking home the top prize. It had been that long. So, as "Chicago" was being developed, there was no real reason to think it would take off the way that it ultimately did. As Marshall explained recently in a retrospective interview with The Hollywood Reporter, naivety was a helpful aid for him during production.

"I was blissfully naive in many ways, specifically of how it would do. At that time, live-action musicals were just dead. 'Moulin Rouge!' had played the year before, and that helped open the door. But I was very much aware that musicals just weren't being accepted. I thought it would be a small, niche film that a few people would see."

Indeed, 2001's "Moulin Rouge!" went on to find a great deal of success, taking in $179 million globally against a $50 million budget. But it was hard to factor that in during this movie's development. And, more importantly, even a broken clock is right twice a day. So was "Moulin Rouge!" a fluke? Or could Marshall truly break the movie musical curse. (Spoiler alert: he broke the curse hard.)

The financial journey

Miramax had a sense that it had an awards season contender on their hands, and released the film under the wire at the tail end of 2002, with "Chicago" initially hitting theaters on December 27, 2002. It was a somewhat modest release, opening on just 77 screens and scoring a $2 million opening in major markets across the U.S. But platform releases were far more effective in pre-pandemic days, with studios doing a slower rollout to build hype. There were, in the past, multiple roads to financial success. It wasn't always about that first weekend as a do-or-die concept.

Case in point, this movie never got higher than number three on the charts even after it expanded nationwide. But word of mouth and strong critical buzz kept it churning week after week, hitting a high point two months later on Valentine's Day weekend, where it took in $12.6 million. That was right in the lead up to the Oscars, which would be held on March 23, 2003 — and with "Chicago" securing an impressive 13 nominations, interest was high amongst the moviegoing public.

All told, the movie collected a huge $170.6 million domestically, nearly matching what "Moulin Rouge!" did worldwide. Internationally, the movie also did excellent business, pulling in a further $136 million for a grand total of $306.7 million. All against a relatively modest $45 million budget. To top it all off? "Chicago" would go on to win Best Picture, beating out the likes of "Gangs of New York" and "The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers," as well as Oscars for costume design, editing, sound, art direction and Best Supporting Actress (Zeta-Jones). Not bad for a first-time feature, eh?

The lessons contained within

No matter what one thinks of movie musicals in general (to put my cards on the table, I'm generally not a fan), it's pretty poetic in a Hollywood dream sort of way what happened here. A first-time director who was not originally supposed to be pitching this movie essentially willed it into existence at a time when musicals were not a safe bet. Despite so much seemingly working against it, "Chicago" was a success in just about every measurable way. It's hard not to feel a little romantic about something like that.

From a studio perspective, many wise decisions were made here. For one, Marshall was a guy who had proven his worth in theater, and clearly had passion for this particular source material. Chaining him to "Rent" might have been like putting a square peg in a round hole. Passion, so often, breeds better results. It was also very wise not to over-budget this thing, with the movie costing even less than "Moulin Rouge!" So sure, let Marshall make his passion project, but keep it under control. It was the healthy balance between art and business that movies so often strive for yet so rarely achieve.

That, coupled with recognizing that this was a bonafide awards season contender, even in a year that saw Martin Scorsese's "Gangs of New York" released by the same studio, was the right call. They also gave it the perfect release at the perfect time, rather than potentially doom it by going wide right off the bat. It is worth pointing out that, in the aftermath of "Chicago," a wave of other successful musicals followed, including "Phantom of the Opera," "Dreamgirls," "Sweeney Todd," "Mamma Mia!," "Les Miserables," and many others, all the way up through "La La Land" which, very nearly, also took home the Oscar for Best Picture.

All of this is to say: just because something hasn't worked in a while, doesn't mean it can't work in the right hands. In the end, people just want a good movie.