After Avatar: The Way Of Water, It's Time To Revisit One Of The Greatest Star Trek Movies

In 1975, Greenpeace — the global environmentalist activist group — launched their successful "Save the Whales" campaign, designed to raise awareness for the world's dwindling whale population. Their goal was to ban commercial whaling worldwide, a practice that, according to the International Whaling Commission, peaked in the 1960s. Happily, their campaign was successful. In 1986, commercial whaling was indeed banned in the United States. Additionally, "Save the Whales" became a widely known slogan, and many Greenpeace supporters sported the organization's bumper stickers, helpfully spreading the word on the issue. The slogan became so well known, in fact, it even came to be mocked by comedians and satirists.

Greenpeace has been watchful ever since, keeping an eye on environmental malfeasance and monitoring popular culture for messages that they can discuss on their website. Recently, Greenpeace posted an essay, written by James Hita and Zane Wedding, all about the ups and downs of James Cameron's new blockbuster "Avatar: The Way of Water," now playing in theaters. Hita and Wedding criticize Cameron's unfortunate tendency to appropriate indigenous cultures to create his alien Na'Vi, but also his tendency toward positive environmental themes. The "Avatar" films are, on a certain level, revenge fantasies that use sci-fi genre tropes and cinematic violence to symbolically wipe out the bullheaded arrogance, violence, and plunder-forward thinking of the world's colonialist military forces.

This is especially felt during the climax of "The Way of Water" when one of Pandora's tulkun — a hyper-intelligent whale species that is hunted by human whalers — leaps out of the water and collapses violently on the deck of a battleship. It's a standout moment in an amazing action climax.

Save the whales? In this case, the whales save us. And it's not the first time Hollywood sci-fi has turned to this messaging.

Save the Whales

Cameron, it should be noted, is an outspoken environmentalist who has worked with organizations such as Global Green, and who regularly touts the positive impact of adopting a vegan diet. There can be no doubt that Cameron sharply recalls the Save the Whales campaign, and that the hyper-intelligent whales in "The Way of Water" were very likely a direct nod to Greenpeace's efforts.

That nod also, of course, evoked another major event of 1986: the release of Leonard Nimoy's sci-fi comedy "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home."

When "Star Trek" first made a move to cinemas in 1979, the tone of the show became both expansive and grim. "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" saw a bitter, angry Kirk (William Shatner) having to struggle with being separated from his crew for many years. It was grand, but also notably dour. In "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan," Kirk was aging out of his job, facing an old acquaintance he unwittingly had left for dead. His ship was trashed in battle and his first officer died. In "Star Trek III: The Search for Spock," he deliberately blew up the Enterprise during an unsanctioned mission to resurrect a dead friend. He and his crew were now fugitives.

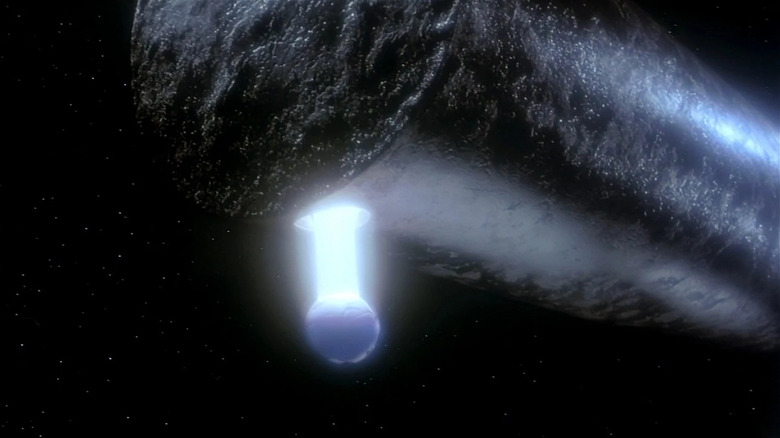

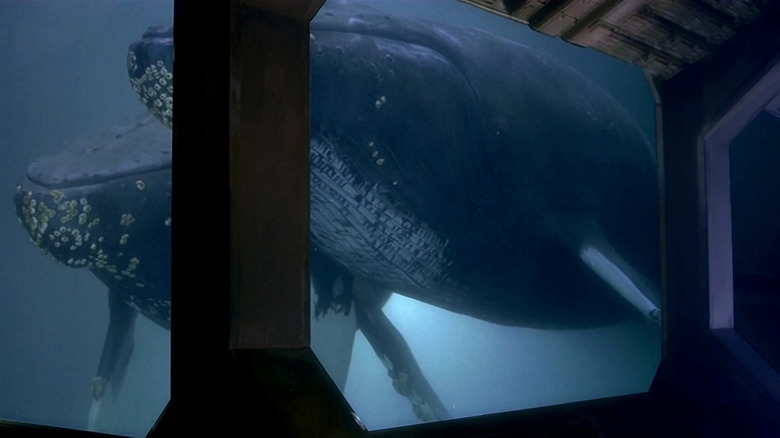

By "Star Trek IV," it seemed high time for the tone to be lightened. Nimoy provided with a whimsical story of the Enterprise crew, on board a derelict Klingon ship, traveling back in time to 1986 to, of course, save the whales. It seems an ineffable and powerful space probe had begun emptying Earth's oceans, looking for humpback whales, a species that had been hunted to extinction a century before. The only solution was to secure a pair of whales from Earth's past.

There be whales here!

The majority of "Star Trek IV" is devoted to amusing fish-out-of-water humor as the stuffy and formal utopians of Gene Roddenberry's idealized future have to contend with backward tech, currency acquisition, and cussing in public. Kirk is called a "dumbass," and retorts with a "double dumbass on you!" It's the lighthearted moments that most audiences may recall from "Star Trek IV," and the film was a massive mainstream hit; until the 2009 "Star Trek," it was the most financially successful film in the franchise.

The "Save the Whales" plot was — and is — a rather blatant environmental message. In "Star Trek IV," Catherine Hicks plays Dr. Gillian Taylor, a cetologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium where a pair of humpback whales are being kept in captivity. Dr. Taylor is given ample screen time to explain why protecting whales is important, and even shows shocking video footage of whales being hunted. She is addressing a group of visitors to the aquarium, but she's really talking directly to the "Star Trek IV" audience. She wants to save the whales herself.

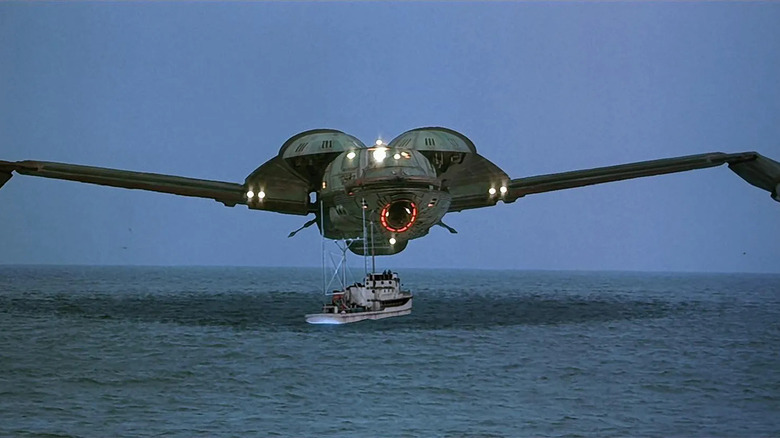

Thanks to the interference of a group of visiting time travelers, she can have her wish. "Star Trek IV," like "The Way of Water," gives fantastical sci-fi magic to activists, allowing them to more forcefully and decisively protect the Earth. Dr. Taylor only has the power of a modern human, and often feels powerless to stop hunters that would crassly kill off a whale out of greed and spite. If only she had a cloaked Klingon vessel. One of the film's more notable shots is of a spaceship materializing directly in the way of a hurled harpoon. That's certainly symbolic.

Sci-fi as a means of justice

Explaining the complexities and fineries of biodiversity are, an activist might tell you, difficult to sum up in a few moments. If a 1986 cynic should burp out "why should I care about the whales?" a Greenpeace advocate would likely require a lot of time to put the cause into a larger environmentalist context. A fantastical story like the one in "Star Trek IV" explains it more clearly: if we don't save the whales, a gigantic tubular space probe will empty our oceans and kill us all. That's pretty easy for a modern sci-fi fan to wrap their heads around.

"The Way of Water" depicts a species of whales that is intelligent, can communicate with the Na'Vi, and is still being hunted for its brain oils (the oil, when extracted, can expand human lifespans back on Earth). Cameron, perhaps one of cinema's least subtle filmmakers, argues that if whalers don't leave their prey alone, an army of the creatures will lay waste to your ships. In Cameron's environmentalist fantasy, the whales need no protectors. They can fight back for themselves. That seems to be the crux of the "Avatar" films. Those who had been destroyed or colonized are given the fantasy powers to fight back. On a very base level, there is catharsis to be had there.

"Star Trek IV," conversely, gave activists the fantasy tech to protect the whales themselves. Different means, different attitude, but perhaps the catharsis is the same.