The Velvet Underground: Todd Haynes On His Approach To The Doc And What The Music Means To Him [Exclusive Interview]

The Velvet Underground is the music that feels like home to me. I discovered them at age 13 when I found "The Velvet Underground & Nico" at my local library. As Jonathan Richman phrases so succinctly in Todd Haynes' "The Velvet Underground," I thought, "these people would understand me." They've been my favorite band ever since.

Haynes is the perfect filmmaker to helm a documentary about The Velvets. The director's first short film, "Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story" — which remains unreleased officially, due to music rights issues — told the story of its titular star from an incredibly heartfelt perspective ... with Barbie dolls.

My introduction to Haynes was "Velvet Goldmine," which made me fall head over heels for the auteur's work. Haynes initially had hoped to make a David Bowie biopic, but when he couldn't get the rights to the musician's songs, he had to get creative. "Velvet Goldmine" is a love letter to glam rock with incredible performances from Jonathan Rhys-Meyers and Ewan McGregor, as well as an amazing soundtrack. Speaking of amazing soundtracks, Haynes is also responsible for "I'm Not There," which tackles the life of Bob Dylan through multiple actors, and the results are spectacular. Music is a theme that runs throughout his work, even playing a vital role in films such as "Carol," which isn't really about music at all.

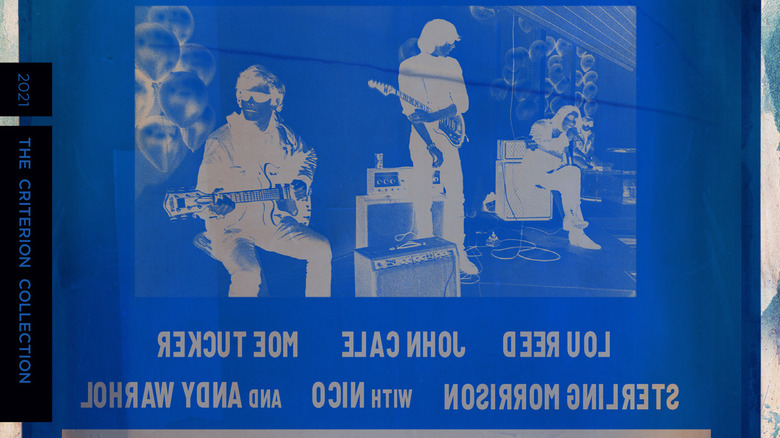

When I learned Haynes would be the one tackling The Velvet Underground's story, I was unbelievably excited. Like the band it chronicles, this documentary is utterly unique. Whether you're a longtime devotee or new to the gospel of The Velvet Underground, the movie is a great watch. I was lucky enough to sit down with Haynes ahead of the Criterion Collection release of the 2021 film to discuss the Velvets' influence, his approach to telling their story, and delving into Lou Reed's past.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

'It's hard to think of contemporary music without The Velvet Underground at the kicking-off point'

As both a huge fan of your work and someone who's been completely obsessed with this band since I was 13 years old, I'd love to hear about your relationship to The Velvet Underground — how and when you discovered them, and what they mean to you.

Sure. Wow, I discovered The Velvet Underground really not until college, and in many ways I felt like I had already been circling the wagon with so much music that is inconceivable without The Velvet Underground. And that's the way sometimes we all discover stuff in those years, is in circuitous ways where you're almost building backwards to the sources and origins of music and influences. Because I was already very much into David Bowie and glam rock and punk rock, and a lot of, of course, the more recent indie rock that was out at the time or that would be coming out throughout the '70s and '80s and '90s.

It's hard to think of contemporary music without The Velvet Underground at the kicking-off point. Lester Bangs called The Velvets the beginning of modern music, that modern music begins with The Velvet Underground. And of course that's an arguable position one could make about popular music and where you locate various shifts in its ethos.

But I think I get it. I think there was something that was happening at the later part of the 1960s or coming out of the 1960s with all of that energy and all of that optimism and all of that desire to give voice to what was happening in the world and what a certain generation was experiencing, where people started to also talk about the harder aspects of existence. And the darker and the murkier sides of what it means to be a person walking the earth. I think that's something that The Velvet Underground did in rock and roll, at least, before anybody else. And it opened up what was possible for certain music to sound like, and of course what music would be describing.

I think that is what you saw completely being developed and in all the music genres that followed it. And it's why people looked to The Velvet Underground and how much they inspired bands who were able to hear the banana record at the beginning, and how much it almost inspired more bands than it experienced success at the time.

Their influence is so deep. For me personally, it felt like that. It felt like an invitation to a creative sensibility, an erotic sensibility. Something about it connoted everything that they were describing in underground cultures of the '60s in New York. Before you even read the lyrics, you felt like you understood that and it permeated the sound of the music.

'I knew that the film would need to be different from other rock documentaries in two distinct ways'

I love that answer. Whether you make a biopic or a documentary, it's not a typical one. "The Velvet Underground" is unique and experimental, like the band. Like the VU did with music, the film pushes the boundaries of what we think a rock doc can accomplish. Can you speak a little bit about your approach to telling this story?

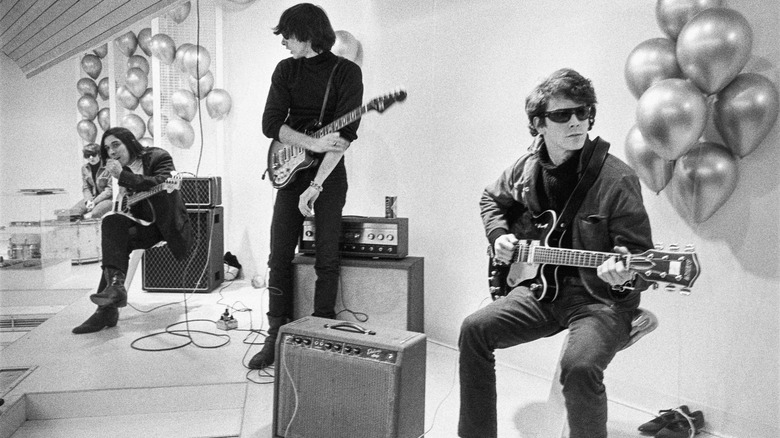

Sure. I was asked if I would be interested in doing a documentary, which I'd never done before, about The Velvet Underground. And it was an immediate yes. But I knew that by saying yes to that, that who they are as a band and as an idea, and then the reality of the fact that there's no footage of that band in the traditional sense that we think of bands, and particularly in rock docs being filmed, and having promotional materials and having live concerts and all of that stuff that goes along with materials associated with music, didn't exist with The Velvet Underground.

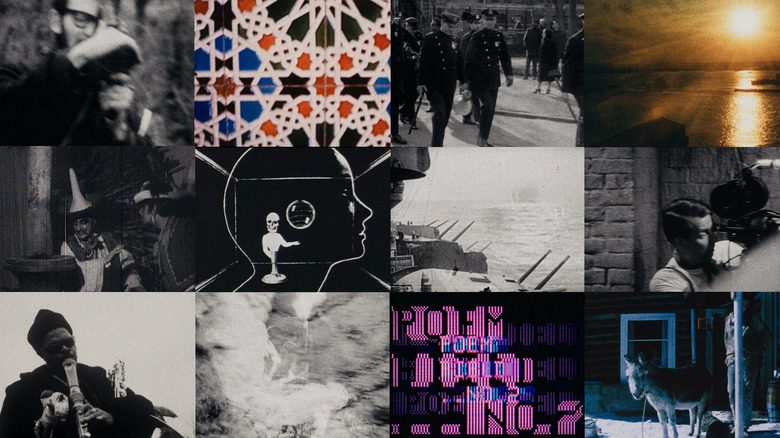

But what did is that they were part of the art cinema of Andy Warhol. And so just by that very distinction, they occupied a place that no other band could ever occupy and the kind of images that we associate with them. Also, incredible photo archives of just amazing photographers' work that explored the Factory years and the '60s. But I knew that the film would need to be different from other rock documentaries in two distinct ways that got me very, very excited about this project.

The first was that it should just look and feel like nothing else, and that it should be driven by the images that were coming out and that were surrounding this band and, in many ways, almost produced this band from avant-garde filmmakers and avant-garde art makers in the 1960s. And how much that was a cross-pollination of not only different artists being exposed to each other's work, but also a multimedia yearning to break down the boundaries between genres of art and have artists start making films and filmmakers start going to happenings and live events, and dancers and poets and everybody mixing up and meeting up.

So that was all there. I wanted the film to feel like you were literally feeling that at a visceral level visually. The avant-garde cinema that we would use as a set or tapestry to telling the story, would almost be leading the experience over and above the testimonials and the narrative storytelling of interviewees or whatever. And I wanted it to only be people who were there. So I would at least have that as a bracket of, this would be about people who were there. Obviously, the surviving members of the band, but anybody who witnessed it in real time.

Then the other thing I was really interested in bringing to it was a real consciousness about a kind of queer sensibility that existed in this very unique, pre-Stonewall, almost undefinable moment in counterculture that was epitomized by The Factory and Andy Warhol, but permeated a lot of the arts. And even if some of the members of The Velvet Underground weren't necessarily all what we would call gay, they identified with a kind of transgressive relationship to heteronormativity, a sense of being outsiders, a sense of wanting to be around drag queens and queer people and go out with these people at night and do what they did and take the drugs they were taking, and really find the likenesses between this sensibility.

And you see how different that sensibility really was when they went to the West Coast. That particular kind of edgy, urban queerness wasn't really being exhibited in the '60s counterculture on the West Coast the way it was in New York City and other places on the East Coast. So those elements I just wanted to bring together in how to tell the story, because I felt that they were so seminal to this music, and things that we forget about with this band.

'We wanted to bring everybody onto the film'

Was it difficult to get John Cale and Maureen Tucker to participate in the film?

No, it wasn't. I wanted to bring John in right away, obviously from a welcoming position. And really anybody who we could contact, we wanted to bring everybody onto the film. The only person we really failed and who was still around is Doug Yule, who just didn't feel like participating for whatever reason. I begrudgingly accepted it, but I was disappointed that he wasn't going to take part.

John was the first person we really went to. The first person we interviewed was Jonas Mekas, because he had just turned 96 years old and he was such an important central figure within the avant-garde film world that this music came out of, and was often literally the backing track or the backing band for all of these film series that he would curate constantly. And the filmmaking put together Jack Smith and John Cale and Tony Conrad and all these people at that Clinton Street apartment, that eventually Lou Reed would shack up into.

So we got Jonas on film. It was the last filmed interview that he would be in. And in the DVD release, there's additional material from Jonas's incredibly insightful, sharp, brilliant interview, as well as additional material from Jonathan Richman's amazing interview, and Mary Woronov.

It was an amazing interview. I watched it, it moved me to tears.

You mean the additional feature?

Yeah, yeah.

Wasn't it insane what he —

When he was talking about how grateful ... Yeah.

The end, where he really starts to cry and thanks the people that put him in touch with this band at those tender years of his in Boston. And also just the ability for an artist like that to talk about other artists, this group, in the ways he does, where he talks about them as if they were painters, painting color palettes and color tones that were specific to different records or different songs.

Only somebody who really was inspired as an artist, as he says, as a student, not a fan. He really makes that distinction in the way he talks about how they embraced him and what they saw in him at such a young age. It's very cool. Very unexpected. I mean, I knew he was a Velvets fan. I knew his beautiful work and music and his own work. But yeah, that interview floored me, as many others of them did.

'Jonathan was everything'

I was going to ask you how you wound up reaching out to Jonathan Richman, specifically.

I mean, he was somebody who ... he doesn't do a lot of interviews in general, Jonathan. And although this band is such a seminal part of his own evolution as an artist, he doesn't talk a lot about them, either. So we were really lucky that he said yes, and that he gave us so much time and that he brought his guitar to that session. Where it became this other voice that was illustrating what he was explaining in real time, and it almost became a sort of unconscious soundtrack to what he was expressing so beautifully.

But one of my criteria for making the film was to only, as I said, use people who were there, and that excluded the generations of artists and writers and musicians who could tell us all the reasons how The Velvet Underground inspired them and moved them and made them want to do what they do. There would be a lot of amazing people in that category. But Jonathan was everything. He was there. He was literally there for almost 80 concerts. He was literally the backstage kid, the fixture of the Boston Tea Party venue shows.

But he was a fan and he was a student, as he says. Those perspectives were so manifest in him, so he provided the point of view of many of the people who would be inspired by the band and whose careers would be taken off from listening to this music. But he was also somebody who was so present and such a unique witness. He's given a very special place in their story.

'We put everything into the film that we could possibly find'

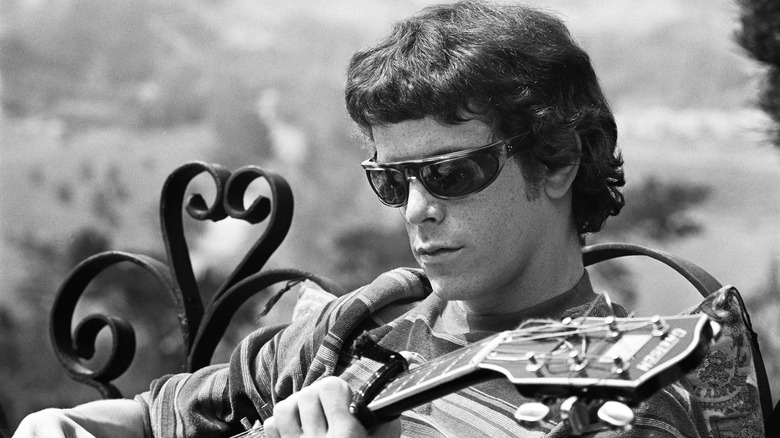

Despite half the original band members no longer being with us, you really could feel the presence of Lou Reed and Sterling Morrison in the film. And part of it is the brilliant use of those screen tests, but also hearing them describe things in their own words. And I love that you included Reed saying that he was writing about pain, because that gets to the heart of so much of his music. What was it like trying to unearth the past of such a mythical figure?

It was a sort of structuring absence that was our biggest creative challenge, I think, in putting together the movie. I wanted to stay true to the new interviews and the way they looked that we created for the film, of which there would not be one for Lou, but we drew from all the audio clips of past interviews, anything we could find where he spoke about The Velvet Underground on tape. And there wasn't an infinite amount, but we put everything into the film that we could possibly find.

Then we saved those clips of him on film for the end, one of them being the interview that he's giving around '73 with Andy Warhol in the room at Interview Magazine with his silver fingernails. And then finally the 1972 Bataclan Concert in Paris, where you see him on stage reuniting with John Cale. And you see that Nico's there and she would be performing with them as well.

I think by holding those things back, it also created this desire for Lou that the film can never absolutely fulfill. And it shouldn't. We should be left with more desire for Lou, and more of a feeling of wanting to get to know who he was and how complex he was. I think that was achieved, in some ways, by the accident of him not being there physically — that he hovers over, in and around it, and we have to keep projecting into that ourselves. It's the only thing that could have happened because he wasn't with us, but I think it actually serves the power and the influence that he has in a way that we didn't anticipate.

A director-approved Blu-ray + DVD special edition of "The Velvet Underground" is available now from The Criterion Collection.