The Bridge On The River Kwai's Real Screenwriters Didn't Get Credit For Decades

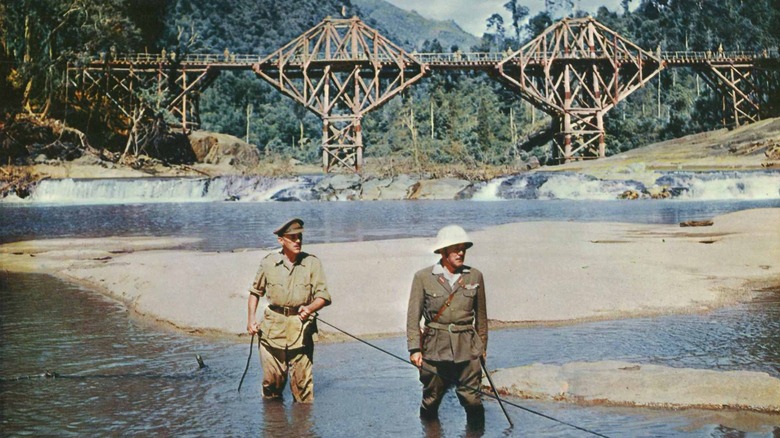

1957's "The Bridge on the River Kwai" marked one of the finest achievements in Hollywood history by presenting both a taut, suspenseful World War II story and a tale of psychological degradation under the oppressive weight of a P.O.W. camp. Director David Lean's masterful command of pace and tone is assisted by nuanced and engaging performances from Sir Alec Guinness, William Holden, and Sessue Hayakawa. And the screenplay, based on the novel by Pierre Boulle, is beautifully structured, building to an explosive climax that's almost secondary to the implosion that's been carefully developed across the whole movie.

The screenplay was credited to Boulle, and he won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. While he wrote the source material, the screenplay actually came entirely from other writers, who were kept under wraps. Between Boulle, Lean, and producer Sam Spiegel, many people officially involved with the movie would take some credit for the work. But the true screenwriters wouldn't see their credit restored until decades later, when the controversy around their political affiliations could finally fade.

Their names were Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson, and each served as the primary writer for a large portion of the movie's development. In the mid-'50s, they were still blacklisted by the Hollywood establishment for alleged involvement in the Communist Party, which led to their taking refuge and jobs overseas. At the time of the movie's release, Sam Spiegel and others, including star William Holden, played a role in hiding Foreman and Wilson's involvement with the movie, but rumors circulated even then.

Foreman and Wilson

The need to conceal the identity of the movie's true writers was paramount. They may have been responsible for delivering the basis for what was sure to be a hit movie, but their relationship to the Communist party had already tanked their careers and reputations. There was no sense including them if the movie's producers wanted to avoid scandal. In fact, it wasn't their first time seeing their work diminished.

Years earlier, Carl Foreman had written the screenplay for the Gary Cooper classic "High Noon," a tense psychological western that used its heightened setting as an allegory for the Red Scare. In particular, its story of a marshal being targeted by criminals he locked up long ago was the basis for a series of questions about loyalty and community. This man has his back against the wall, and none of the people he's served over the years will do anything to help him.

For his troubles, Foreman was effectively exiled to the UK. Endless House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) investigations gave his name a mark that producer Stanley Kramer wanted nothing to do with. Michael Wilson, on the other hand, left Hollywood shortly after the release of the hit 1951 melodrama "A Place In The Sun" and 1952's "5 Fingers." Faced with a similar plight to Foreman, he worked in the same way, often doing uncredited passes on screenplays. One major difference was his contribution to the pro-worker "Salt of the Earth," a low-budget film set in a New Mexico mining town.

Rumors spread

Even as time passed and HUAC's influence began to dissipate, writers like Carl Foreman and Michael Wilson had a hard time denying the "unfriendly witness" label. Producers and directors would gladly incorporate these writers' contributions to screenplays, knowing it was their precise mix of dramatic skill and social conscience that let them produce such excellent, engaging work. They just wouldn't get the proper credit.

With "Bridge on the River Kwai," producer Sam Spiegel's investments were clear in every frame. The spectacle of the movie's location photography in what was then Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and the incredible bridge at its center (as well as the explosion that makes up the climax of the movie) contributed to the film's $3 million budget (via The Numbers). For the movie to be a smash, nothing could go wrong.

As Pierre Boulle received credit for the movie, critics noted how impressive it was for the French novelist to make his screenwriting debut with such an exquisite film. According to AFI, film industry trade magazines soon began spreading rumors about who was really responsible for the screenplay. When it was reported that Foreman had written the screenplay in one news item, Spiegel would deny it in another. When Boulle admitted to not writing the screenplay after receiving an award from the British Film Academy, Spiegel claimed it was because his contributions were just one piece of the overall product.

Lead actor William Holden, set to receive a then-revolutionary share of the movie's gross, also said that claims of Foreman writing the screenplay were "hogwash." But AFI noted that without Foreman, the movie wouldn't have been made at all.

Credit restored

In fact, per AFI, Carl Foreman had optioned the rights to Pierre Boulle's original novel in the first place. He tried to tap Zoltan Korda to direct, but the venerable filmmaker's similarly distinguished brother Alexander rejected the screenplay on account of its being "anti-British." That led Foreman directly into the arms of producer Sam Spiegel and director David Lean, who immediately took issue with what Foreman had written and put new writers on the project.

Spiegel and Lean were picky, bringing on writers like Calder Willingham for revisions and rewrites and then bringing on somebody new when they didn't like what was written. Reportedly, that was when Michael Wilson was brought on to finalize the script. It was he and Foreman who, separately, came up with the lion's share of what became "Bridge on the River Kwai." Their names were axed from the movie, and their Oscars that went to Boulle would only be properly awarded in 1985, years after both of their deaths.

Spiegel and Lean would collaborate again on 1962's epic "Lawrence of Arabia," and again Michael Wilson would be hired to work on the screenplay. When Robert Bolt was brought on by Lean to replace WIlson, moves were made to cut Wilson's credit yet again, ultimately erasing him from two of Lean's greatest epics.

Thankfully, Foreman and Wilson have both had their work acknowledged in the decades since — although that doesn't erase the injustice of their contributions having been scrubbed away in the first place.