'Unbreakable' Was A Superhero Movie Years Ahead Of Its Time

The worldwide theatrical release of M. Night Shyamalan's Glass this week has prompted a rush of appreciation online for Unbreakable, the first in what became a trilogy of superhero films spread out over nineteen years. With its deconstructionist take on superhero mythology, the 2000 flick, starring Bruce Willis and Samuel L. Jackson, anticipated the great wave of 21st-century comic book movies and TV shows grounded in pseudo-realism.

Everything from The Dark Knight trilogy to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, with its initial emphasis on tech and science over magic, surely owes a big-screen debt to Unbreakable. On the small screen, shows like Netflix's recently canceled Daredevil have taken a late cue from Shyamalan by focusing more on human drama and showing us street-level vigilantes who operate in the shadows in do-it-yourself costumes. One subplot on the final season of that show even sought to establish a realistic psychological framework for a super-villain by showing us his backstory with a sympathetic therapist, à la Split, the surprise backdoor sequel to Unbreakable.

As we await Glass and the conclusion to the story begun in these two movies, let's take a look back at Unbreakable and what made it so special and ahead of its time as a superhero film.

We often think of the age of modern superhero movies as having started with Bryan Singer's X-Men, and to an extent, that's true. Released in midsummer of 2000, months before Unbreakable's Thanksgiving debut, X-Men feigned realism but had less reverence for the source material and ultimately sent the genre off on the wrong track in the early 2000s. If its director didn't take comic books seriously, why should executives at 20th Century Fox or any other studio? And so we got films like the first Fantastic Four and the Ben Affleck Daredevil.

Whereas Singer banned comic books from the set of X-Men, Shyamalan's film actually had scenes set inside a comic book store. It even took pains with its opening text to explain comic book culture to the audience. (The fact that it had to do this back in 2000 is retroactively amusing, given what came later.)

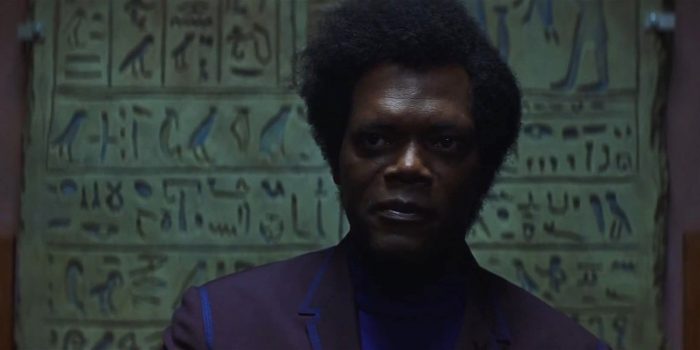

The idea that superheroes are figures of contemporary myth like the Greek myths of old might not seem groundbreaking in 2019, but even in 2000, Unbreakable went further with it than usual. The movie's thesis statement, as it were, comes in a monologue given by Jackson's character, a comic book art dealer named Elijah Price, who suffers from a rare genetic condition that renders his bones all too breakable. With hieroglyphics hanging on the wall behind him, Price says:

"I've studied the form of comics intimately. I spent a third of my life in a hospital bed with nothing else to do but read. I believe comics are our last link to an ancient way of passing on history. The Egyptians drew on walls. Countries all over the world still pass on knowledge through pictorial forms. I believe comics are a form of history that someone somewhere felt or experienced. Then, of course, those experiences and that history got chewed up in the commercial machine, got jazzed up, made titillating, cartooned for the sale rack."

The notion laid out here that comic books are a form of history is not so different from what is argued in a recent Vox article about why cultural criticism matters. That article talks about the "psychologically predictive elements of works" like The Hateful Eight (another film starring Jackson). Art seems to have a way of tapping into the collective unconscious or assimilating patterns via cultural osmosis that can indeed give it a predictive edge.

In this way, Unbreakable perhaps inadvertently foresaw the coming of the comic book movie millennium. Both it and its very belated sequel took stories of super-powered men and boiled them down to their psychological essence as tales of extraordinary individuals. They then applied that essence to the template of the thriller, adding family drama and troubled backstories to the characters to keep themselves situated within the realm of plausibility.

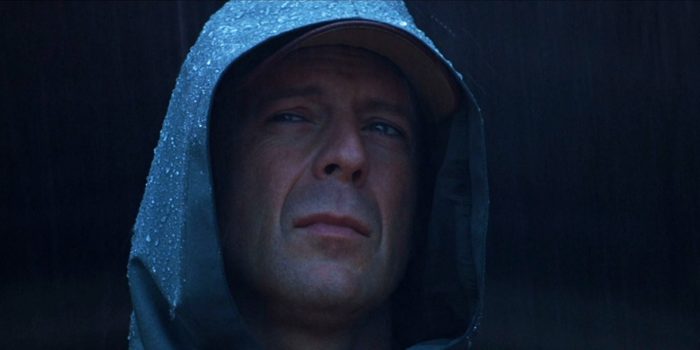

Another facet of Unbreakable's pseudo-realism is how it shows the grayer side of its hero. David Dunn (Willis) doesn't exactly make the best first impression when we meet him. He's the kind of guy who slides his wedding ring off his finger when an attractive woman sits down next to him on the train. When the train derails in a horrible accident, however, he's the sole survivor, and this is how he comes into contact with Price, who has been watching the news and waiting to see a story of miraculous survival like Dunn's.

Price's theory is that if he and his brittle bones represent human frailty in the extreme, then there must be someone on the opposite end of the spectrum like Dunn who is, as the movie's title says, "unbreakable." Dunn is not only invulnerable, of course ... he's also super strong. There are all sorts of ways to show super strength on-screen, but Unbreakable chooses to frame Dunn's as a moment of self-discovery.

In one of the film's most memorable scenes, we see him bench-pressing all the available free weights — plus some paint cans — in his basement at home. His young son, who looks up to his father like a god (Greek or otherwise), stands by as the sole witness to this display of superhuman ability. The boy will later become so convinced of Dunn's invulnerability that he draws a loaded gun on him in an effort to make Dad see what he refuses to accept.

Maybe one reason why Unbreakable has maintained such a loyal fan following over the years is that it isn't just a superhero film. Some of the genre's best entries have dabbled in the tropes of other genres, whether it be Logan and the Western or The Dark Knight and crime films. As much as it's a superhero origin story, Unbreakable is also just a drama about a man who denied his calling in life but who learns to find himself again and be true to his purpose.

When Dunn first meets Price, he talks about how getting a note on his car teasing that he was special ("How many days of your life have you been sick?") allowed him to wake up in the morning and not feel sadness for once. In a flashback to his college days, we're eventually shown how he came away from a car crash physically unscathed, but used the wreck as an excuse to give up football stardom. He was destined for great things, it seemed, but the decision not to pursue his talents put him on a different path. This has left him restless in his life, feeling like, "Something's just not right."

It's only at the end, when he's at the breakfast table with his son, that we see Dunn come into his own as a happy, well-adjusted husband ... who just so happens to have a secret identity as a headline-making crime-fighter. However, this being an M. Night Shyamalan movie, the story doesn't end there. We're also dealt a last-minute twist.

No spoilers here, except to say that the twist hits the viewer hard and fast before a couple of freeze-frames with docudrama-style text end the movie. Back in 2000, that faux summary of what happened next landed awkwardly in the theater. It seemed like a sloppy finish, which may explain the "weaker ending ... not as good as The Sixth Sense" consensus about Unbreakable on Rotten Tomatoes. Yet while it may not have been executed perfectly, the ending did adhere to comic book tropes and leave the twist sinking in on the way home.

It's ironic that Disney, which now owns Marvel, deliberately downplayed the comic book aspect of Unbreakable. If you go back and watch the first trailer, you can see how they marketed the film as more of an eerie thriller like The Sixth Sense. Owing to this muddled marketing, perhaps, Unbreakable was not a runaway success. While not an outright flop, it fell short of domestic box office expectations, dashing immediate hopes of a sequel.

Seventeen years later, we finally got that sequel. In its own way, Split was rather ahead of its time, too. Instead of a superhero movie, it's a supervillain movie, perhaps the first bonafide example of one we've ever seen. Sure, there's a Joker movie starring Joaquin Phoenix on the way this year, and FX's Legion did premiere on television a few weeks after Split's theatrical release. Numerous other supervillain movie projects are in development or rumored, and yes, we've seen films like Venom last year where the villain was framed more as an antihero. Once again, however, Shyamalan was out in front with his execution of this idea—just as he was all those years ago with Unbreakable.

Unbreakable isn't a perfect movie. In addition to the shaky ending, it features the world's most awkward home invasion and a rather anticlimactic fight scene that is essentially just one man giving another a long, choking bear hug from behind. David's extrasensory perception, while necessary from a plot perspective, also overcomplicates his superpowers, bequeathing him with a crowded skillset where he's not only super strong and invulnerable to sickness and injury, but can also see flashes of people's wrongdoing just by making physical contact with them. Then again, if you break down all the powers Superman has — flight, super speed, super strength, super hearing, X-ray vision, heat vision, arctic breath, bulletproof skin — that's a pretty crowded skillset, too.

However Glass shakes out (read our early review here), Shyamalan has shown that he is capable of crafting compelling superhero and supervillain origin stories. Years from now, if these kinds of movies do go the way of the Western, and some pop culture historian compiles an ultimate guide to the evolution of the genre, Unbreakable deserves an important place in the canon, right up there with early pioneers like Superman and Batman.