Road To Endgame: 'Iron Man' Built The Foundation Of The MCU Using Charm And Military Fantasy

(Welcome to Road to Endgame, where we revisit all 22 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask, "How did we get here?" First up: Iron Man and the foundation of Marvel's messy political outlook.)At Comic Con 2006, Marvel Studios promised an unprecedented four-franchise shared continuity, set to cross over in The Avengers. Thirteen years later, we're waiting (im)patiently for Iron Man to recover from his cosmic loss alongside Captain America, Thor, The Incredible Hulk, the Guardians of the Galaxy, Spider-Man, Doctor Strange and Black Panther, among others, as we head toward a 22-film culmination: Avengers: Endgame.Not only have the aforementioned characters become mainstays of popular culture, the Marvel Cinematic Universe has long since become the highest grossing film franchise in history. It began with Jon Favreau's Iron Man in 2008, a film that feels downright modest by modern blockbuster standards, but one that was tasked with crafting a political backdrop to launch heroes yet unseen.As the foundation of a boundary-breaking, landscape-shifting series, Iron Man is worth lauding. Though, as one of many Hollywood films subsidized by the U.S. government, its relationship to military power is worth further scrutiny, as it impacts both the film's political outlook, and its character-centric story.

A Stark Difference

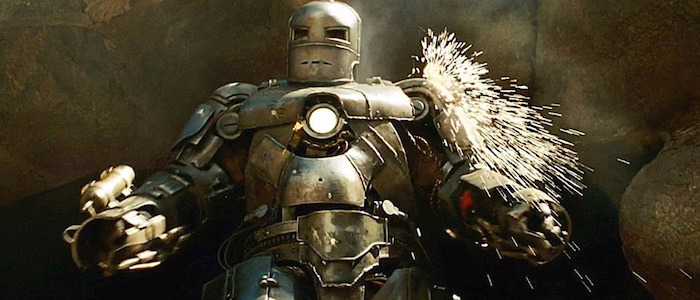

Marvel wouldn't be where it is today without Iron Man. While secret identities were still a staple of the genre, the soon-to-be A-lister shattered the cookie-cutter big screen superhero by revealing his alter ego to the world, albeit to satiate his own ego. More pertinently, Marvel wouldn't have gotten here without Robert Downey Jr.In 1963, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby sought to create an antithesis to the youth movements of the era, turning a capitalist, industrialist and weapons manufacturer into a lovable fixture of Marvel Comics. Forty-five years later, Tony Stark's first film appearance was born through a similar creative stubbornness, as director Jon Favreau fought all opposition to get Downey Jr. into the classic red & gold.An actor whose past drug problems were likely to prepare him for the role in the long run — though the character's trademark alcoholism was eventually swapped out for P.T.S.D. — what made Downey Jr. the perfect Patient Zero for Marvel was his unique ability as a storyteller. Not only was much of his dialogue improvised on set, but Downey Jr. brought to the action genre an oft-overlooked talent: the ability to turn even rote exposition into development of character, be it with a look, a smirk, or by disguising insecurity behind sardonic quips.In the film's Afghanistan-set opening scene, Stark rides alongside American soldiers in their camouflage Humvee. His aura simultaneously attracts and alienates. He has the shine of a playboy billionaire, and a detached allure that arrived just in time for the social media boom and the ensuing age of irony. His humour is to-the-point, despite the emptiness it masks. From the get-go, long before he builds his rudimentary Mark I suit, his first layer of armour is the person he projects himself to be. He is untouchable, yet he commands gravity, attracting everyone in his orbit. However, he's cut down to size by a real-world attack of his own making.The military unit protecting Stark is bombed. Soldiers hired to accompany him are killed in action. Stark himself is kidnapped by Middle Eastern militants, and he becomes a victim of weapons bearing his own name. His key change as a character is catalyzed soon after thanks to a similarly captured scientist, Ho Yinsen (Shaun Toub). A humble physician from Gulmira, Yinsen is framed as Stark's equal and opposite. He uses technology in a way Tony "The Merchant of Death" Stark isn't usually known for, building a device to save Stark's life.Yinsen's battery-powered magnet keeps shrapnel from reaching Stark's heart. This effect mirrors Yinsen opening Stark's eyes to the plight of war-torn regions, often at the hands of Stark Industries weapons, as if to ask:What darkness lies in the heart of Tony Stark, and can it be exorcised?

Fantasy Hero, Political Reality

Iron Man shifted Stark's comic origin from '60s Vietnam to modern Afghanistan, allowing for a more literal, more contemporary articulation of America's military industrial complex. This approach was embodied not only by the film's villains, but its hero.Superhero movies had been picking up steam for nearly a decade, but Iron Man was the first to set its story against a recognizable geopolitical reality. Stark visits the Middle East to sell deadly weapons to the U.S. military, weapons he openly compares to the Manhattan Project, which his father worked on decades earlier. Charming as Stark is, his outlook here is detestable, and he's forced to face up to it once he's kidnapped, bearing witness to how and where his missiles are actually used."Peace means having a bigger stick than the other guy," Stark tells a reporter early on, who rightly responds: "That's a great line, coming from the guy selling the sticks." At the beginning of the series, Stark profits, albeit unwittingly, from selling to "both sides" of the wartime equation, something his villains (Obadiah Stane, Justin Hammer and Aldrich Killian) are guilty of in every Iron Man film.At its core, the first Iron Man is a tale of an American war profiteer having a change of heart, symbolized by the arc reactor in his chest, a glowing promise of untold possibility. It's a hopeful idea on the surface, centered around a man who sees his weapons fall into the wrong hands and acts accordingly. He contends with his legacy by shutting down the weapons' division of Stark Industries, before taking on the mantle of an armed vigilante. But herein lies the problem with Tony Stark.While he works to get his weapons out of "the wrong hands," be it the Ten Rings militants or the man behind the curtain, Jeff Bridges' Obadiah Stane (to say nothing of the U.S. military, to whom Stark has been more than happy to sell), there's nothing delineating the wrong hands from the right ones. To Tony Stark, the egocentric futurist, the right hands remain his own.The film's final battle, fought between Iron Man and "bigger Iron Man" (the comics' Iron Monger) is an attempt to contrast Stark's newfound righteousness with the warmonger he once was. However, this climax still pits two titans of weapons technology, Stark and Stane, against each other for ideological control of weapons of mass destruction; their conflict plays out in the form of two weaponeers trying to out-weapon one another.We know how Stane would use his legion of iron suits — the same way he uses all weapons, selling them under the table to profit from a never-ending war — but the film never positions Stark as an alternative, or as someone who might better the status quo. He employs distinctly U.S. military tactics like unsanctioned foreign intervention. He hands out extrajudicial murder like candy, and he puts civilians at further risk. In fact, Stark's impetus for intervening at all is the mention of Yinsen's hometown of Gulmira, making his mission one of reckless revenge, rather than an altruistic act. That this is never contextualized as anything but heroic leaves a sour taste, when one considers the destructive real-world implications of America's presence in the region.However, the conflation of super-heroism with real-world U.S. militarism might not be accidental. The film's geopolitical backdrop — proxy wars, a destabilized Middle East, and America's general military industrial complex — is framed only as a product of private capitalism and foreign militia, rather than U.S. government policy (let alone policy that Stark enables). In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, violence is something the U.S. military merely responds to, rather than something it causes. This is by design, though the details of this design weren't made public until Pentagon documents were released under the Freedom of Information Act five years later, including a Department of Defense agreement that locked the film in to a military-approved script.Which brings up a pertinent question: Is Iron Man military propaganda?

The Guy Selling the Sticks

The twisting of the film's political backdrop to deflect real-world blame must be discussed, if we're to have a complete understanding of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Iron Man is, after all, one of the many Hollywood films partially funded by The Pentagon. So, a story directly (or even indirectly) critical of America's role in the Middle East was likely never an option, even in a film that seeks to critique violence in the region. The result is the MCU being built on a shaky political foundation, one that leans, more often than not, towards supporting the American status quo.Stark stops building weapons because of the missiles that fall through the cracks. His objection, as it pertains to the film's depiction of war, is his weaponry being sold to "the other side" and used to kill Americans. However, the effects of these weapons when used by Americans to kill anyone else is never called into question. This falls perfectly in line with Department of Defense's involvement in the film, leasing out locations and equipment insured for $10 million (you can download the D.O.D. Production Assistance Agreement for Iron Man here, obtained by the folks at SpyCulture under the Freedom of Information Act).A Production Assistance Agreement from the Pentagon locks a film in to a military-approved version of its script. Iron Man wasn't the only Marvel film to receive military assistance either; Iron Man 2, Captain America: The Winter Soldier and Captain Marvel, films with their own issues with how they approach military politics, were also made with military input. Military-funding is common in American cinema and television — how do you think the Transformers movies got all those tanks? — but it's rarely mentioned in fan-discussions about Marvel, let alone by western critics increasingly fixated on the Chinese government's role in shaping the blockbuster landscape. Modern Hollywood isn't free of American government influence, and neither is the world's preeminent blockbuster franchise.A pertinent example of the military's role in Iron Man comes courtesy of a deleted scene, in which one U.S. soldier tells another that "people would walk over hot coals for the opportunities he has." This line never made it to the finished film, but its original incarnation was "people would kill themselves for the opportunities he has." This phrasing was strongly objected to by Phil Strub, the D.O.D.'s chief Hollywood liaison since 1989, in an apparently heated on-set confrontation with the film's director. On one hand, it's a minor occurrence. The line didn't matter in the long run since it was cut from the film, but it's also emblematic of a larger problem. The mere notion of a U.S. military member mentioning suicide, even in a joking context, was enough for Strub to call for censorship — in the literal government censorship use of the word — presumably, due to the barely-addressed epidemic of veteran suicides.It isn't hard to see how Iron Man might have military appeasement on its mind. Thus, the mere implication of America's ill-decisions in the Middle East was likely a non-starter, even in a film about the misuse of weapons of war.

Is Iron Man Military Propaganda?

In short, yes. It's designed, with direct influence of the U.S. government and paints a skewed narrative of American foreign policy, one in which the U.S. military neither causes nor exacerbates any of the destruction seen in the film. The blame is passed entirely to industry and to hostile foreign entities, a narrative decision whose ripple effect can be felt throughout the series.A number of studio films each year have the distinction of military funding, so it's hardly shocking that a company like Marvel, despite its anti-weapons manufacture flagship character, would tie up with Defense Contractor Northrop Grumman in 2017. A chief complaint to this comic partnership was the ethos of Tony Stark, which fans used to lambast Marvel for its hypocrisy. But this hypocrisy wasn't new; it had been built into Marvel's DNA ever since Iron Man hit cinemas. The possibility of military partnership isn't a bug in the Marvel machine. It's a feature, and it's one we haven't really stopped to grapple with as the Marvel Cinematic Universe has grown in global influence.The MCU often sees heroes struggling with power and how to wield it, but its questions of intervention are locked within an invisible framework, one that allows for lip-service to questioning power, yet one that implicitly comes down on the side of power itself, forever protecting the American status quo in the larger Marvel narrative.The closest thing to a counter-example comes from the other side of the globe. A story like Yeon Sang-ho's Psychokinesis, the 2018 Korean superhero dramedy, wouldn't fly in the MCU. Yeon's film features a working-class father gaining powers and fighting off police violence against the poor; in the process, the film seeks to hold real-world power structure accountable, rather than using metaphorical villains that let real ones off the hook (Metaphors don't quite work as intended when the real issues being alluded to are also present in the narrative, but remain unaddressed).Time and time again, Marvel's villains have been adjacent to real-world structures, but they are never the structures themselves, despite embodying their flaws. In this film, Iron Man isn't tackling an unjust system. He's simply fighting a few bad apples. The film's big-bad, Obadiah Stane, isn't framed as evil for selling lethal weapons, period, but for selling these weapons to America's enemies. In the world of Iron Man, one created in part to appease the D.O.D., civilian casualties and unjust interventions are never framed as American problems.The cinematic language we've grown used to speaking over the last decade is, essentially, incomplete, until we decode this fundamentally propagandist aspect of some of our most beloved blockbusters. Filling the gaps with our own conversations and critiques becomes vital when such vast swathes of our culture claim to speak truth to power, but ultimately take its side.This same problem exists at the core of American politics, wherein many who (rightly) speak out against war and human rights abuses under a given administration tend to fall asleep at the wheel when their "side" is in power, committing equally heinous war crimes while deporting families. It's no wonder, then, that all Marvel needs to do is make its villains seem like the greater of two evils, so that its heroes — Black Panther aside — can serve contemporary definitions of order.It would be easy enough to ignore the series' latent propaganda, were it not so influential on the stories being told.

Stark in Stasis

Change in outlook lies at the heart of the MCU. But can its heroes affect real change when they're most often concerned with protecting the status quo?In terms of story, the biggest victim of the film's muddled military approach is the character of Tony Stark. Take, for instance, the early scene in which a reporter questions him about his weapons contract with the military. In response, Stark comments on the media's lack of reporting on military-funded projects in areas like crops and healthcare, a deflection that turns him, and the film, into mouthpieces for the American government.Whether or not one has qualms about propagandist throwaway lines, inserting this exchange has a negative effect on the narrative. The film's own attempts to contrast Stark with Ho Yinsen — whose life-saving use of technology is part of Stark's awakening — are undercut, given that Stark already seems to use his military money for healthcare. In effect, Stark learns little he didn't already know from Yinsen's life-saving actions. The film seeks to turn a heartless war profiteer into a humanitarian. However, Stark taking pride in his ostensibly "good" military contracts serves to dilute and lessen his journey, the way Han Solo shooting second in Star Wars dilutes his eventual turn to selflessness.This problem is further exacerbated when Stark decides to cease arms manufacture. His decision is rooted in whom his weapons are sold to, as opposed to his weapons being sold at all. Stark is given enough reason to hold his company accountable, but neither he, nor the film, hold accountable the real-world military forces he enables in the process.

Marvel’s Vague Villains

The Ten Rings terrorist militia — who speak an assortment of languages, from Arabic, Urdu and Pashto to Dari, Mongolian and Russian — have no discernible cultural or geographical origin, and thus, no discernible politics either. While they refer to Stark as "the most famous mass murderer in the history of America," the film fails to specify who used Stark's weapons for murder, against whom, and the reasons these militants retaliate against American military interests.In the film's geopolitical context, to rob the villains of clear objectives is to rob the premise of its full potential. The violence Stark's weapons are used for is never fully contextualized, because painting a clear picture of the villains and their motives would mean portraying the U.S. military destruction they push back against. Therefore, Stark's own remorse and reckoning — the very forces driving the film — have little dramatic grounding.This lacking political framing plays counter to Iron Man's seemingly "real world" setting. The film's texture is real, but its politics are a fantasy, concocted to paint American military power as a neutral (if not necessary) default, in a world where non-specific foreigners and selfish billionaires bear the all responsibility of war.Even so, this responsibility, as it pertains to Stark's atonement, is only ever framed as power fantasy. Stark separates villains from civilians using artificial intelligence; he depends entirely on algorithmic facial recognition to determine, unilaterally, who lives or dies. Rather than an alternative to military power, Stark is merely framed as a complimentary force. He is positioned (at times, through the film's own dialogue) as carrying out what the military should, but hasn't been granted approval to.Stark delights in righteous displays of violence and technological might, in ways that are at odds with his character arc. There's little remorse to be found when punching bad guys to upbeat metal seems so indulgent.

The Long Game

Iron Man features moments of reflection a-plenty, usually between Stark and Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow), and in ways later Marvel films seldom do. However, the film doesn't stop to let Stark reflect on the irony of trying to rid the world of weapons by creating new ones. Obadiah Stane even states this irony outright, but before Stark has a moment to consider his words, Stane is killed in an explosion.The film regularly fails to frame its own politics in an honest light. However, this ends up a surprisingly solid foundation for Marvel's long-term narrative, even if by accident. Many of the things early Marvel films fail to consider or contextualize are woven into the text of later entries. They're dramatized, in retrospect, as mistakes made by Tony Stark.Iron Man sees Stark, and the Marvel universe at large, identifying a problem but failing to provide a concrete solution. In the process, the film unwittingly sets up one of modern pop culture's most interesting long-term stories, in which Stark (as well as teammate and eventual rival Captain America) struggle to find satisfying answers to the problems of responsibility plaguing modern geopolitics. The rest of the series builds admirably on this thread of Stark as a problem solver who creates new problems. However, it also magnifies the narrative flaws set into motion by a series built on propaganda.Eventually, even with its muddled, military-fawning foundation, the Marvel Cinematic Universe does, to some degree, begin to course-correct, even though it circles back around to this problem in Captain Marvel. As the years go by, the MCU wrestles with ideas of militarism and intervention with increasing complexity — but has the series gone far enough? That remains to be seen.Despite finding himself in another hapless predicament — trapped in space the way he was once trapped in a cave — the Tony Stark of Avengers: Endgame is no longer the Tony Stark of Iron Man. The eleven years and twenty films in between saw an array of evolutions in outlook, scope and style across the shared Marvel chronology, making this vast difference feel like a singular journey, cobbled together from seemingly disparate franchises.In the end, for better or worse, Marvel will have kept audiences invested for over a decade, as the world at large continues to wrestle with similar questions of power ad infinitum. We're in the endgame now.

***

Expanded from an article published April 2, 2018.