From 'Patton' To '1917': The 20 Best War Movies Of The Last Half-Century

War is hell but it sometimes provides the backdrop for great movies. The recent Blu-ray release of 1917, followed by the 50th anniversary, this week, of the Oscar-winning Patton, starring George C. Scott, is as good an excuse as any for cinephiles to hunker down in the trenches of an impromptu war movie marathon (especially if you're stuck at home right now due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic).

With that in mind, here's a mission for you, soldier: work your way through this chronological list of the best war movies of the last fifty years. "Best" is ultra-subjective, of course, but when you're Alamo-ed up in a fort of pillows in your living room and there's nothing good on television, few of these movies should disappoint.

What defines a war movie? There are many quality films, set during times of war, where the drama plays out tangentially to the main battlefield conflict. The anime film Grave of the Fireflies, for instance, shows the devastating impact of World War II on the lives of Japanese civilians, specifically, two children. This list is focused less on war-adjacent historical dramas (Westerns like Dances with Wolves, or even Holocaust dramas like Schindler's List being included in that definition) and is more focused on films where the action occurs on the frontlines of the military conflict.

Steven Spielberg once said, "Every war movie, good or bad, is an antiwar movie." Others have argued that the opposite is true and every war movie is a pro-war movie. The movies on this list are about soldiers in battle, but they're not necessarily pro-war—even if some of them do stray toward one-sidedness.

Having a protagonist and antagonist is virtually unavoidable in storytelling, even the postmodern, perspectival kind that doesn't rely on fixed sympathies. However, there's a fine line between being patriotic and propagandist. What we're interested in here isn't recruiting-tool movies that explicitly glorify a suspect cause, downplaying the humanity of the enemy in favor of rah-rah American exceptionalism. The bread-and-butter of this list, rather, is human-centered stories that play out in the so-called "theater of war."

1. Patton (1970)

Patton is perhaps most well-known for its opening speech, where George C. Scott — in character as the eponymous World War II general — stands uniformed in front of a giant American flag. "Americans have never lost and will never lose a war," he tells his offscreen troops. The self-assured jingoism of these words takes on a shade of irony when you consider that moviegoers first saw this scene while the U.S. was mired in a losing war in Vietnam.

In 1970, while that was going on overseas, 20th Century Fox was busy distributing classic war movies on the home front. January saw the release of Robert Altman's MASH, which followed army doctors "snatching laughs and love between amputations and penicillin" during the Korean War. MASH earned an Oscar nomination for Best Picture, but it lost the award to Patton, while Scott famously refused his own Best Actor win. (On this list, we're counting forward from early April 1970, when Patton landed in theaters, otherwise MASH would surely make the cut, too.)

Director Franklin J. Schaffner was hot off the success of Planet of the Apes when he helmed Patton. Screenwriter Edmund H. North also had a background in science fiction, having penned The Day The Earth Stood Still. He co-wrote the script with Francis Ford Coppola, who only managed to save his job on The Godfather because of this film's success.

Patton is as much a character study as it is a war movie. Like other eccentric officers we'll soon meet, the general is a poet-warrior; he believes in reincarnation. Looping trumpet sounds remind him of his past life, some two thousand years ago, as he steps out of his jeep and walks among the ruins of a city where the Romans and Carthaginians fought. Yet hubris impedes him in this life and in the end, he is left to ponder how "all glory is fleeting."

2. The Deer Hunter (1978)

"This is this." After the Vietnam War ended in 1975, Hollywood began addressing the war in a more head-on fashion. 1978 was the year when films like Hal Ashby's Coming Home and Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter started penetrating the mainstream market. Both films confronted the psychological effects of the war on American soldiers. At the 51st Academy Awards, they dominated the major categories, with The Deer Hunter taking home the awards for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actor for Christopher Walken.

There's not much historical basis for the Viet Cong subjecting POWs to Russian roulette games. However, The Deer Hunter is less concerned with history and more concerned with the toll of traumatic stress on working-class types (in this case, steelworkers), who were thrust into life-or-death situations as they shipped overseas to fight for their country. Russian roulette and the gambling dens of Saigon, where old friends meet their fate in the worst way possible, are simply stand-ins for the randomness and brutal chaos of war.

The Deer Hunter continued the '70s winning streak — begun with Mean Streets, The Godfather Part II, and Taxi Driver — that helped cement Robert De Niro's reputation as the greatest actor of his generation. It was John Cazale's final film before his death and it was the film that earned Meryl Streep the first of her many Oscar nominations. It also boosted the profile of John Savage, whose character undergoes a harrowing journey from his own wedding to a bamboo cage full of river rats to a VA hospital where he's had both his legs amputated. After watching this movie, you'll have a lump in your throat anytime you hear, "Can't Take My Eyes Off You."

3. Apocalypse Now (1979)

Apocalypse Now is the culmination of a decade of New Hollywood cinema, when directors like Francis Ford Coppola, William Friedkin, and Peter Bogdanovich were at the height of their artistic reign, encountering each other at stoplights and trumpeting their critical and commercial success from the sunroof of stretch limos. The movie brats of the 1970s had their unofficial pack leader in Coppola, whose cinematic river odyssey — through Vietnam and into the wilds of Cambodia — bears a symbolic weight that extends beyond the war movie genre into Hollywood history and the heart of darkness itself.

In Apocalypse Now, the audience boards a patrol boat for a ride through the underworld, where it encounters Wagnerian helicopter attacks, surfers and sauciers, jungle tigers, dancing Playboy Playmates, sampan massacres, puppy dogs, pagan idolatry of mad colonels, T.S. Eliot quotes, and ritual water buffalo sacrifices. Purple haze and the smell of napalm engage the senses as the movie pushes its characters to the brink, much like Coppola did with himself and his cast.

The film's many production problems have become the stuff of Hollywood legend. Coppola fell victim to a nervous breakdown, thrice threatening suicide. Lead actor Martin Sheen suffered a heart attack brought on by alcoholism. (Filming of the hotel room intro took place on Sheen's 36th birthday while he was drunk). Supporting actor Dennis Hopper reportedly had cocaine funneling back to him through official channels to fuel his performance as an American photojournalist turned crazed Colonel Kurtz acolyte. Marlon Brando — Coppola's old Godfather collaborator, who the director re-enlisted to play Kurtz — also had his own vices, which dictated how the film would be shot. He showed up on the set so overweight that he had to be dressed in black and filmed from the neck up or in shadow, using a body double.

They were fighting their own filmmaking war, the kind where real human cadavers could have shown up as props. It was sheer insanity but it resulted in one of the greatest movies of all time. Coppola and Hollywood would never be the same.

4. Das Boot (1981)

If The Hunt for Red October and Crimson Tide are the first titles that come to mind when you think "submarine movie," then chances are, you haven't yet experienced Das Boot. Wolfgang Petersen's 3-hour epic takes us aboard a German U-boat during the Second World War, where the hardscrabble existence of sailors exists at a harsh remove from the benighted politics of the surface world. The film's principal actors dubbed their own voices into English for the U.S. release. Jürgen Prochnow, known to horror fans as Sutter Cane in In the Mouth of Madness, stars as the U-boat's jaded captain, who rails against his masters in Berlin and their empty radio propaganda and who needles the one Nazi on his sub for his gross underestimation of Winston Churchill.

At one point, the sub's crew members — bearded and wet-haired, dressed like real seamen — enter the alien environment of a luxurious topside dinner aboard another ship, where clean-cut, uniformed officers greet them as "heroes" with the Sieg Heil salute. The contrast between these officers and the U-boat sailors is stark. The men of The Boat (the English translation of Das Boot) represent the grimy reality of those who fight the wars waged by politicians.

Depth charges rock The Boat and its hull creaks ominously, threatening to collapse, as it tests the limits of how deep it can dive. Das Boot ventures further off the map than most war movies, to a place in international waters where nationalities no longer matter. All that remains is a common humanity, tested by grueling conditions. Prochnow would later reunite with Petersen for Air Force One, playing the foreign dictator whose capture set in motion the film's Die-Hard-esque plot.

5. Platoon (1986)

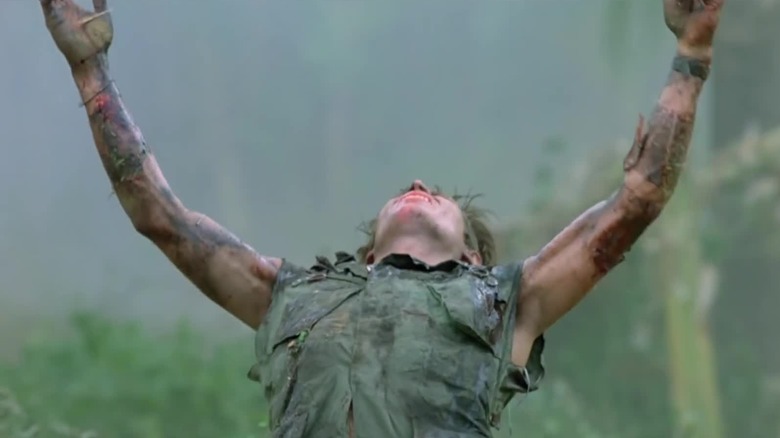

Platoon came from a personal place in that writer-director Oliver Stone was a real Vietnam vet, someone who had served in the U.S. Army during the war. The tagline for the movie is, "The first casualty of war is innocence," and that informs how Stone approaches his subject. A young Charlie Sheen (then, just filled with the blood of a tiger cub) stars as Chris Taylor, a wide-eyed infantryman who gets caught between the opposing forces of his two platoon sergeants, Elias and Barnes. Willem Dafoe plays Elias and Tom Berenger plays Barnes; the movie earned them dual Oscar nominations for Best Supporting Actor.

Elias lounges shirtless on a hammock in the Underworld, a hutch decorated with Christmas lights where men suck bong hits and dance to Motown music. Jefferson Airplane and Smokey Robinson fill the air and Elias channels a line from Janis Joplin: "Feeling good's good enough." Meanwhile, Barnes and his men perpetrate war crimes, shooting innocent villagers and taking part in gang rapes. Against this backdrop, Chris — who came to Vietnam as a volunteer, hoping to discover himself and not be "a fake human being" — undergoes a traumatic journey from innocence to experience.

Platoon was Stone's answer to the pro-war John Wayne film The Green Berets. Its musical theme, Adagio for Strings, conjures up immediate images of a helicopter takeoff where a man comes running out of the jungle too late. Scenes like this worked their way into the collective imagination and remain an indelible part of film history. In 1989, Stone would return to the canvas of Vietnam with Born on the Fourth of July, which illuminated the plight of veterans coming home from the war.

6. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

I once heard someone say, "Full Metal Jacket was good, but it was all downhill after the fat guy killed himself." That's reductive and not especially eloquent but for all I know, it may mirror the sentiment of John Q. Moviegoer. Vincent D'Onofrio gained seventy pounds to play the role of the overweight Marine private in question—nicknamed "Gomer Pyle" after the naive sitcom character. Pyle's sweet tooth for contraband doughnuts earns him the ire of his bunkmates in boot camp after his punishment blows back on the whole group of them. They decide to haze him in his bunk with toweled soap bars and before you know it, he's forming a talky relationship with his rifle and giving the camera the trademark Kubrick Stare.

The piquant drama building up to Pyle's eventual latrine breakdown is exacerbated by the abuse he endures from his drill instructor, whose creative cussing and cadence calls ("Ho Chi Minh is a son of a b*tch / Got the blueballs, crabs, and the seven-year itch!") inject a shot of life and black comic relief into the first half of Full Metal Jacket. Movie drill instructors begin and end with the late R. Lee Ermey and I'm still waiting for someone to deepfake him into a shout-off with the J.K. Simmons character from Whiplash.

The second half of the movie belongs to Matthew Modine's "Joker," who is set adrift as a military journalist in Da Nang, where streetwalkers step to Nancy Sinatra and solicit soldiers with the oft-quoted, "Me so horny, me love you long time." Pyle killed himself and his drill instructor; Joker earns the dubious writing on his helmet, "Born to Kill," by gunning down a teenage Vietnamese girl who has been sniping the men in his unit. Full Metal Jacket isn't necessarily Stanley Kubrick's best all-around film, but even a lesser Kubrick film is better than ninety percent of other movies.

7. Glory (1989)

Back in December, I wrote a separate /Film article about Glory, which I'll link to at the end of this section. My eighth-grade history teacher showed us the movie in class and there's one important scene in it that I neglected to discuss in that article. In many ways, it's a scene that serves as a linchpin for the film and what it is about.

The night before their charge on Fort Wagner, the soldiers of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment are gathered around the fire in their camp. For some of these men, it will be their last night on earth. The men are humming and clapping in unison, taking turns speaking before lapsing back into a chorus of, "Oh, my, Lord, Lord, Lord, Lord."

I've had their singing stuck in my head for a good twenty-five years or so, ever since that day I was first exposed to the movie in history class. There's not a single non-black face to be found in that scene, which immediately distinguishes Glory as something different from your standard Civil War depiction (like, say, Gettysburg, which we'll get into next).

An impertinent college buddy of mine once dismissed Morgan Freeman as a one-trick actor who always plays the same kind of roles. Some of that may result from typecasting. If memory serves correct, on Inside the Actor's Studio, Freeman himself once acknowledged that he was the go-to "gravitas" guy. During this scene in Glory, however, Freeman slips into a different voice, like he's channeling the ghost of some old Southern preacher. Denzel Washington, the son of an actual Pentecostal minister, steps up after him, reminding us why he won an Oscar for this movie and why Glory is the best Civil War film ever made.

8. Gettysburg (1993)

With its emphasis on the glory and valor of old Virginia and de-emphasis on the role of slavery in the war ("We should have freed the slaves, then fired on Fort Sumter"), Gettysburg veers uncomfortably close, at times, to being a pro-Confederate Lost Cause film. Watching it almost feels like observing a Civil War reenactment, where you've got a bunch of modern men playing dress-up in bushy beards and blue and gray uniforms. The movie did, in fact, utilize Civil War reenactors as extras. In this case, the human figurines — media mogul Ted Turner's toy soldiers, as it were — just so happened to include war movie hall-of-famers Martin Sheen and Tom Berenger, who play Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and James Longstreet.

On the Northern side, Jeff Daniels is particularly good as Joshua Chamberlain, a colonel tasked with defending a hill on the Union Army's left flank during the battle that marked the Civil War's turning point. No sooner are he and his unit relieved and sent to the middle than they find themselves facing the onslaught of Pickett's Charge. This is where the movie redeems itself with an engrossing depiction of the conception and execution of battlefield strategies. It may seem like a relic of a pre-Glory mindset, but its treatment of the Battle of Gettysburg will come as catnip for history nerds.

It should be said that Gettysburg isn't a film for viewers with short attention spans. Then again, its butt-numbing length may be perfectly suited to current binge-watching standards and the unique predicament of being cooped up at home during a pandemic. Owing to its small-screen roots as a TNT miniseries, the 4-hour film (which received a limited theatrical release long before that became de rigueur with Netflix's award movies) leans more into saluting and speechifying than blood and grime. Familiar faces like Sam Eliott come and go from the narrative as the film offers a diffuse, time-traveler's view of the war, showing how friends who fought together in previous wars found themselves on opposite sides of the North-South conflict.

9. Saving Private Ryan (1998)

For some viewers, the most memorable aspect of Saving Private Ryan may be its depiction of D-Day. Steven Spielberg had been making World War II films since he was a kid and he opened this one with an extended sequence set during the pivotal amphibious invasion of Normandy. The film spends over twenty minutes on the beach with American soldiers as they disembark landing crafts and are chewed up in a swift and merciless fashion by German machine gunfire. Bullets tear through hapless swimmers, unzipping red blood clouds from their bodies underwater, while on the beach, radiomen get their faces blown off and heads without helmets lose their luck equally fast.

This carnage has a spectacle to it but it means more, later, when characters we care about face their own unique, personalized deaths. The medic leaking blood from holes in his chest. The sniper whose crackshot aim finally fails him. The Jewish soldier with a knife driven through his heart. The captain firing his handgun at an approaching Tiger tank.

These deaths might not mean as much, either, were it not for the time we've spent getting to know these characters. Quiet moments in candlelit churches and on the steps of buildings put us in touch with the film's aching human core. Edith Piaf plays on the phonograph as the men recount stories from back home of women they once knew and brothers they lost. When Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) says, "Earn this. Earn it," he's not only speaking to Private Ryan (Matt Damon), the man he's sacrificed himself to save. He's speaking to the audience and all the living.

10. The Thin Red Line (1998)

Back in the 1990s, when Martin Scorsese still watched new movies, he appeared on an episode of Roger Ebert & The Movies, where he spotlighted The Thin Red Line as his second favorite film of the decade. Here is what he had to say about it:

"There's no star. The film has a deliberately loose structure and the story is told through multiple voiceovers and points-of-view. The Thin Red Line is actually the story of every soldier who took part in the endless battle to secure Guadalcanal. The Thin Red Line works very differently from most films. As you watch it, you wonder, what is narrative in movies? Is it everything, and if so, is there only one way to handle it?"

The Thin Red Line definitely brings a more arthouse sensibility to the war room than Saving Private Ryan. The film's perspective, such as it is, is more like that of a spirit, setting itself down in men's minds, observing them from the inside and outside as they search their souls and come into conflict with each other. Interweaving its various subplots into an all-knowing Malickian mosaic, the film essentially offers a God's-eye view of the war.

As abstract as that might sound, The Thin Red Line is still more straightforward than some of Terrence Malick's later films, insofar as it lets real scenes solidify and play out between characters, be it Witt and Welsh (Jim Caviezel and Sean Penn) or Tall and Staros (Nick Nolte and Elias Koteas). As his plane takes off, Staros speaks of his men as sons, saying, "You live inside me now. I'll carry you wherever I go." Maybe, the film gently suggests, the reverse holds true and there's some divine omnipresence out there, checking in on its children even as they go about waging war.

11. Three Kings (1999)

American films about wars in the Middle East are often as dry as the desert they are set in. Three Kings, by contrast, is a war dramedy with heart. This was director David O. Russell's breakthrough film, and in it, he uses the Gulf War as an arena for an early George Clooney heist. (The director and actor infamously also used the set as an arena for their own real-life scuffle). Whereas Ocean's Eleven would bring the glitz, Three Kings brought the grunge: dirtying the faces of its greedy antiheroes in sand and cow's blood as they endeavored to steal a bunker full of Kuwaiti gold bars.

Rapper Ice Cube holds his own in the movie, as does Spike Jonze, who manages to go totally incognito as a wiry high school drop-out with a Southern accent. You would never think this same goofball would go on to become a celebrated filmmaker in his own right (Jonze's first feature, Being John Malkovich, hit theaters three Fridays after Three Kings.)

What sticks in the memory more than anything with Three Kings is the moral shifts its characters undergo. Clooney comes across as an unlikeable thug when he threatens to shoot a man just so that he can get his hands on the gold. There comes a moment of truth later, however, where he witnesses a cruel injustice and it impels him toward his final selfless act of the movie.

Mark Wahlberg's character only cares about the spoils of war, too, until he learns empathy through torture at the hands of an indignant captain in Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard. While his interrogator addresses him as "dude" and "my main man" and relates how the war has killed and maimed his own family, Russell intercuts flashes of Wahlberg's character imagining his own wife and child back home. By the end, the Americans are changed men, and what we are left with is an image of liberated refugees looking back at us with a body wrapped in white.

12. Downfall (2004)

Most of the films on this list offer stories told from an American or Hollywood perspective, with a few breaking from that pattern to offer a German, Japanese, or British perspective. Downfall's perspective is that of a fly on the wall in a room full of Nazis. What's most unsettling about it is not that it depicts monsters; it's that the monsters wear human faces. Downfall shows evil chained to mundane reality. It lets us witness the fall of the Third Reich in realtime.

An endless cascade of memes poured forth from this German-language film and its scenes of an apoplectic Hitler with shaky Parkinson's hands, ranting in his underground bunker about all the ways his generals have failed him. As the noose tightens around Adolf (the late Bruno Ganz), his girlfriend, Eva Braun, is still swing-dancing at parties, where people laugh and drink champagne until reality comes exploding in on them.

Godwin's law dictates, "As an online discussion grows longer, the probability of a comparison involving Nazis or Hitler approaches." Those comparisons, while inevitable, do come cheap but they don't always match the true picture of a given situation. Yet consider this scenario: Downfall shows a deranged leader, who's been responsible for concentration camps, lashing out in all directions as the world around him descends into chaos. Even staunch loyalists can see that he's acting irrationally. Some of his fiercest enablers turn on him out of self-preservation; others just stand paralyzed outside the room or by his table as he abandons his own people to death and condemns everyone but himself.

Hitler didn't have Twitter to air his unfiltered madness, so in his final hours, he can only blow up at people behind closed doors, ordering executions and screaming of traitors who will drown in their own blood. As civilized as we might think we are, Downfall takes us back to April 1945 for a germane snapshot of history that is only seventy-five years removed from our own era. That's a lifetime for most people, but in the grand historical scheme of things, it's not so long ago.

13. Letters from Iwo Jima (2006)

We all know the sight of the six U.S. Marines raising the flag on Iwo Jima in World War II. It's the subject of an iconic photograph and a famous war memorial near Arlington National Cemetery. In Flags of Our Fathers, director Clint Eastwood explored how the men behind the second flag-raising (there were two, and some men were misidentified) got caught up in a patriotic myth that was bigger than any of them.

In Letters from Iwo Jima, Eastwood and Japanese-American screenwriter Iris Yamashita tell the other side of the story, focusing on the Japanese soldiers who fought to defend the embattled "sulfur island." Ken Watanabe stars as Kuribayashi, the general overseeing the operation, whose sensible orders sometimes go unheeded. As the situation on Iwo Jima worsens, retreat is not an option for some of Kuribayashi's commanders, who would rather maintain their honor as soldiers of the Emperor, shouting, "Banzai!" and leading their men in mass cave suicides. J-pop idol Kazunari Ninomiya plays Private Saigo, who witnesses his fellow soldiers detonate hand grenades against themselves, one after another.

One of the few English dialogue scenes in Letters from Iwo Jima comes when the film flashes back to an American dinner party before the war, where Kuribayashi is the guest of honor. He receives a Colt .45 as a gift from an officer there, whose wife asks him, "How would you feel if America and Japan were to enter war?" Kuribayashi explains that he would have to follow his convictions, which are the same as his country's convictions. They proceed to joke about it — all part of the polite dinner conversation — but that Colt .45. follows the principle of Chekhov's gun and will come back into play later.

14. The Hurt Locker (2009)

Before they ever joined the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Jeremy Renner, Anthony Mackie, and Evangeline Lilly all starred together in a little war movie called The Hurt Locker. Director Kathyrn Bigelow crashed the boy's club genre with the POV of a bomb-disposal robot wheeling over desert terrain. Screenwriter Mark Boal, who would reteam with Bigelow for Zero Dark Thirty, takes a thriller approach to the story. What starts out as another jokey day on the job for a U.S. Army bomb squad in Iraq soon becomes a scene of white-knuckle tension that robs the unit of its leader.

Renner's character, Sergeant James, enters the fray as his replacement but he's prone to taking unnecessary chances. It's not long before he's waltzed into the kind of peril where following a red wire unearths a daisy chain of explosives right under your feet. The film opens with the quote, "The rush of battle is often a potent and lethal addiction, for war is a drug." Those words certainly apply to Sergeant James, who doesn't hesitate to sneak off-base in Baghdad but finds himself less equipped to deal with choices on the cereal aisle back home.

At the 82nd Academy Awards, Bigelow beat out her ex-husband James Cameron for Best Director, while The Hurt Locker became the lowest-grossing Best Picture winner of all time—triumphing over Avatar, the highest-grossing nominee (and all-time highest-grossing movie, period, until Avengers: Endgame came along last year). The film's title might sound like a reference to a soldier locking up his hurt, but when James steps off the helicopter for his next tour of duty, you've never seen a man in a bomb suit look happier.

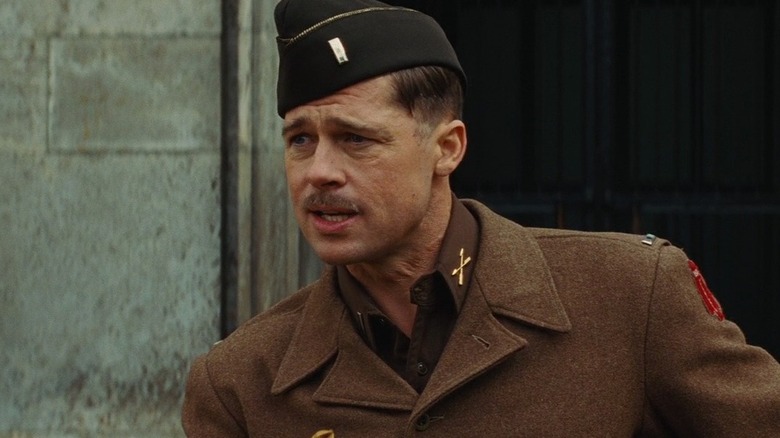

15. Inglourious Basterds (2009)

Quentin Tarantino's best film, Inglourious Basterds, belongs to the men-on-a-mission sub-genre of war movies. Plot-wise, the film borrows from macho antecedents like The Dirty Dozen. Instead of a chateau in Brittany, France, it's a cinema in Paris where the men's mission sends them. Again, the American soldiers pose as non-English speakers and the objective is to eliminate top German brass; but this time, that includes Hitler himself, whose red-faced tirades against the Basterds ("Nein, nein, nein!") may owe a debt to Downfall.

This year, Brad Pitt won the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for his most recent Tarantino collaboration, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Inglourious Basterds sold itself on Pitt's star power and he certainly embodies a rich caricature as Lieutenant Aldo Raine, "the direct descendant of the mountain man Jim Bridger." Yet the funny thing about this movie is how much it sidelines the gung-ho squad that Raine assembles to collect Nazi scalps. This is where Inglourious Basterds departs from the tradition of its forebears: by foregrounding a Jewish woman and a British leftenant and a deal-making Nazi, while the "special team" of the movie's title functions more as a group of barbed-wire wingmen.

It's not really an action movie, per se. You could almost cut the Basterds out of the movie without it impacting the plot too much. The two most important characters in Inglourious Basterds are actually Shosanna and Hanz Landa, played by Melanie Laurent and Christoph Waltz, who were largely unknown to audiences outside Europe at the time. Through them, Tarantino, in his typically talky fashion, is able to retcon history into a tale where victims enact immediate vengeance and the bad guys burn in hell in a movie theater right here on Earth.

16. Fury (2014)

Writer-director David Ayer told People magazine that he "set out to make the ultimate tank movie" with Fury. He succeeded in that aim, putting viewers in the belly of a steel beast (as an Indiana Jones character might call it) with the ever-busy Brad Pitt's tank commander, Wardaddy, and his crew. Forget everything you know about Shia LaBeouf, the celebrity. Sporting a mustache and quoting scripture, LaBeouf, the actor, is in top form as the tank's religious gunner. Michael Pena, Jon Bernthal, and Logan Lerman round out the rest of the crew, with Lerman playing Norman, the green young PFC whose POV serves as the audience's entry point into the gritty world of tank warfare.

Fury was the best American World War II film to hit theaters since Saving Private Ryan. It's also Ayer's best film, perhaps because he actually served in the military and the film had more personal meaning than some of his other work-for-hire projects. That said, the film may not be for everyone, insofar as it delivers an unflinching look at the moral ambiguities of war, showing us scenes where the ostensible heroes could be interpreted as villains.

This includes a scene where Wardaddy forces Norman to execute a prisoner in order to toughen him up, and a scene where the American soldiers decide to play house in an apartment with two German women—one of whom, Emma, winds up forming a connection with Norman and implicitly sleeping with him. The apartment scene, in particular, might be problematic for some viewers, who see it as an unrealistic depiction of a situation where the threat of physical force from soldiers would override any notion of consent.

17. American Sniper (2014)

It's pretty insane to think that American Sniper had the highest domestic gross of any film in 2014, outpacing blockbusters such as Guardians of the Galaxy and Captain America: The Winter Soldier at the box office. The film was not without controversy; in L.A., the word "murder" showed up in spray paint on a billboard for it. Not everyone was enamored of seeing a movie about the marksman with the most kills in U.S. military history.

Chris Kyle, the Navy SEAL sniper played by Bradley Cooper, ships off to Iraq after 9/11 and the first two targets he sees in his scope are a woman and boy. This scene found its way into the first official trailer for American Sniper, an effective piece of marketing that begins in media res and winds itself up tighter and tighter, intercutting flashes of Kyle's life with a thumping heartbeat that grows more elevated as the moment of truth nears. It's not the first time a trailer for a Clint Eastwood movie has eschewed the usual montage approach and instead hooked viewers by letting the eye dwell in-scene. (Think of the first teaser for Mystic River, with Eastwood's voiceover landing on the word "murder" as the camera soars in over a riverside bar.)

Seth Rogen compared the trailer to "Nation's Pride," the propaganda film-within-a-film from Inglourious Basterds. That's an uncomfortable juxtaposition that obscures what American Sniper is really about: namely, the veterans who become damaged goods while they do their duty. Even a storied combat vet like Kyle, who secured the nickname "The Legend," is subject to vulnerability as he serves as a cog in the war machine. The film builds toward a tense rooftop standoff where Kyle takes an impossible shot at a rival marksman from over a mile away. Yet the distance between him and his civilian life back home seems wider.

18. Hacksaw Ridge (2016)

He's the director who once filmed Jesus being whipped 96 times or so and his name can be a polarizing one. However, after being blacklisted in Hollywood for years, Mel Gibson finally made it back into the good graces of Oscar voters with Hacksaw Ridge. Andrew Garfield must really love working with Catholic directors of Christ movies, because 2016 saw him paired with both Gibson and Martin Scorsese on Silence. It was Hacksaw Ridge, however, that netted Garfield his first Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

Hacksaw Ridge is a bloody biopic steeped in pacifism, and if that sounds contradictory, just wait till you meet its main character. The film tells the heroic true story of Desmond Doss, a Seventh-day Adventist who enlisted in the U.S. Army after Pearl Harbor but refused to carry a gun on religious grounds. His status as a conscientious objector doesn't exactly make him popular among his fellow soldiers, who reason that it could potentially endanger their lives on the battlefield. It almost gets him drummed out of the service, but not before he endures a night attack from his bunkmates, much like Gomer Pyle in Full Metal Jacket.

The difference here is that Doss isn't about to go postal on anyone. He keeps his dignity, refuses to rat out his attackers, and becomes a medic who goes on to save many lives by single-handedly roping them over the side of a ridge. The first half of Hacksaw Ridge is all drama, but when it gets to the Battle of Okinawa, the movie starts making up for lost time, deploying flamethrowers and machine guns, mowing down soldiers with frightening rapidity. It's all in service of a tale about a pure-hearted guy who got his hands dirty without ever firing a shot.

19. Dunkirk (2017)

The early-to-mid 2010s marked a slight downturn in the quality of Christopher Nolan's directorial output, as the sure-footed blockbusters of the 2000s, which he had become known for, gave way to clunkier plotting and creakier dialogue. The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar left even the most diehard Nolanites split on whether their favorite filmmaker had fumbled the ball or scored a touchdown (like the wide receiver for the Gotham Rogues in the football stadium Bane blew up).

Suspenseful and sparse on dialogue in favor of pure visual storytelling, Dunkirk marked a great return to form for Nolan. The film shifts between land, sea, and air perspectives as it tracks the evacuation of Allied soldiers from the beaches of Dunkirk, France, during World War II. Here, the word "mole" takes on a double meaning: it could be a German spy or it could just be referring to the long jetty where troops stand waiting to be evacuated. Some troops have the ingenuity to smuggle themselves onto ships as stretcher-bearers ... only to see those ships become sinking death traps as bombs or torpedos catch them. Just when it seems salvation is in sight, the lads are liable to find themselves back where they started, unable to escape Dunkirk.

Nolan has long been preoccupied with time and Dunkirk's score, composed by Hans Zimmer (who else?), brings that to the forefront. The music becomes a ticking reminder that time and fighter plane fuel are running out. By now, Nolan has become such a brand unto himself that he can outgross the likes of Steven Spielberg and David Lean. As World War II movies go, Dunkirk sits highest atop the list of box office earners, with even Saving Private Ryan and The Bridge on the River Kwai falling below its $525 million global haul.

20. 1917 (2019)

Depending who you ask, Sam Mendes may or may not be overtly chasing Mr. Nolan with some of his recent movies. It's hard to argue that Skyfall's plot mechanics are derivative of The Dark Knight in places. Yet oddly enough, despite the implicit hundred-year connection of its title, 1917 almost feels more indebted to Alfred Hitchcock's Rope and Alfonso Cuaron's Children of Men than it does Nolan's Dunkirk.

Like Emmanuel Lubezki (who lensed the long-take wonders of such films as Gravity and Birdman, in addition to Children of Men), Roger Deakins is one of those rockstar cinematographers whose influence in molding the texture of certain films is as present and palpable as that of the director. His fingerprints are all over 1917, but not in a way that's intrusive or calls too much attention to itself. The film simply has a strong cinematographic flavor to it. It sits you down next to a tree, then stands you up and walks you over and pulls you down into the trenches with its characters.

What at first seems like a buddy movie with two soldiers soon twists and turns into an arduous personal trek across no man's land and the landscape of World War I. Not since All Quiet on the Western Front won Best Picture at the 3rd Academy Awards in 1930 has the Great War hijacked pop culture with such a vivid and memorable movie. In a way, that brings us full circle, not just fifty years back, to Patton, but ninety years back, to All Quiet on the Western and some of the earliest war movies in film history.

When he runs across a bombed-out city lit by raging fires at night, George MacKay's British lance corporal is not only carrying on a grand cinematic genre tradition. He's serving as an avatar for humanity as it motion-pictures itself, in real life, through centuries of bloody warfare and struggles to survive eradication.