'Avengers: Age Of Ultron' Balances Gods And Monsters, Bringing Marvel's Legacy Into Focus

(Welcome to Road to Infinity War, a new series where we revisit the first 18 movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and ask "How did we get here?" In this edition: Avengers: Age of Ultron takes a long, hard look at gods, monsters, and the humans in-between.)

How often do we ask ourselves why we created God and the Devil? We've been questioning our own existence for thousands of years – where we came from and what we'll leave behind – so to have those ideas pumped into a $300 million superhero sequel, albeit to varying degrees of success, is something of note.

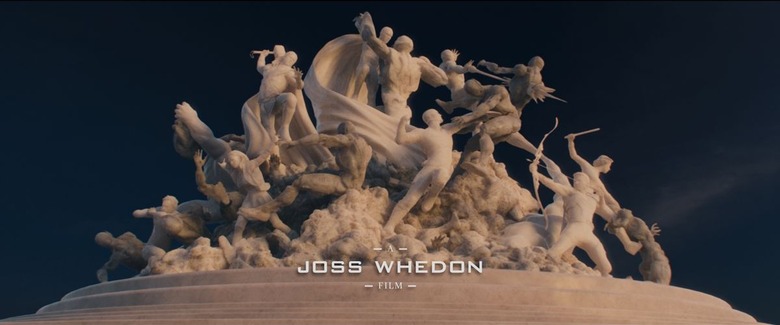

We're well into Marvel being the biggest thing in popular culture with Avengers: Infinity War, but the questions asked by Joss Whedon's medial crossover are of particular interest when it comes to the Avengers' iconography. By 2015, our entertainment landscape had become dominated by the violent Übermensch in a visage of childlike fantasy, and it warranted artistic introspection.

Avengers: Age of Ultron is not some Watchmen-esque deconstruction; then again, neither was the 2009 Watchmen movie, which took straight from the pages of the 1986 comic series rather than drawing from the culture around it. Age of Ultron on the other hand came out a mere two years after the destruction debate post-Man of Steel, which focused largely on civilian causalities. Whether as response to the new tenor of superhero conversation or as a means to set up Captain America: Civil War (or both; the intent isn't mutually exclusive), Age of Ultron places similar debates in its crosshairs, first by making its characters' top priority the protection of civilians, and then by exploring the ways in which they ought to go about it. The film forces the Avengers to contend with their in-world legacy as a means to explore their fictional legacy on-screen.

It's a narrative nexus, building on what came before while setting up Marvel's future, as it attempts to define that very nexus for each of its characters. A mirror to our modern pantheon.

Would You Sacrifice Millions to Save Billions?

Our heroes have thus far been the resounding answer to this question in the form of a negative. In The Avengers, they stopped a nuke launched at New York City as a means of preventing global invasion. In Captain America: The Winter Soldier, they opposed HYDRA's plan to take lethal preventative steps in order to achieve peace. When the decision wasn't theirs to make, and when they opposed the extreme measures taken by shadowy governments, their heroism was clear. It's an ugly idea that villains seem to answer all too easily (see also: Watchmen's Ozymandias) but what of a situation in which our heroes themselves are forced to confront this question?

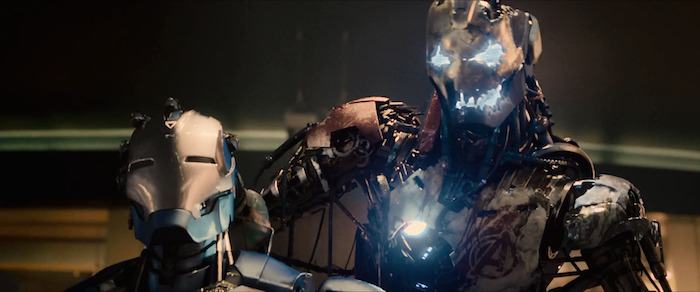

Tony Stark, the futurist who has trouble learning from the past, creates the Artificial Intelligence Ultron (voiced by James Spader). Ultron's mission, logistically speaking, is peace. But it's peace without conscience, not unlike HYDRA's Project Insight, and peace with no care for people. Ultron has the tools to build and to destroy, but he's a reflection of the Avengers without protective instinct. That protective instinct is granted to Jarvis, Stark's A.I. who eventually becomes the answer to Ultron, but Ultron's idea of harmony is a world where humanity is no longer around to muck things up.

To prove his point about the futility of human heroes – people he believes unworthy since they've all been killers at some point – Ultron raises the entire city of Sokovia miles in the air before planning to drop it like a meteor. The result would be human extinction, but the Avengers destroying this meteor before rescuing every Sokovian citizen on it would be a catastrophe too.

It's the O.M.A.C. Project film we may never get from DC, a story of Global Security A.I. run amok that calls into question the responsibility of the superhero – only DC's penchant for characters embodying abstract concepts is replaced by Marvel's feet of clay. The seeds for this massive third act are planted throughout the film, with each Avenger having to contend with the nature of their past and how their actions could dictate their future. As much as Age of Ultron is about humans establishing humanity in the face of a soulless being, it's about why those humans must establish their humanity if they're to keep on being heroes, and characters with stories worth telling.

The Avengers Disassembled

The film's opening scene involves a glorious long-take, not dissimilar from the sprawling action in The Avengers' New York climax. Iron Man, Captain America, Thor, Black Widow, Hawkeye and Hulk function as a single unit, as they partake in what they hope is their final mission against HYDRA. Loki's scepter from their first film has been used for human experiments, and the Avengers believe it's their job to intervene unilaterally. The citizens of Sokovia however? They aren't so happy about these American heroes launching attacks on their soil. Sokovian graffiti portrays The Iron Man as a war profiteer, clutching guns and money in the background of a scene where his drones dictate terms of safety. The Avengers work as a group, but do they work within the world at large?

The Avengers are brought together by their desire to do good. However, they're torn apart by the exacerbation of their fears a la Wanda Maximoff (Elizabeth Olsen), whose scepter-derived abilities fill our heroes' heads with terrifying visions. Tony Stark sees his friends dead at his feet, as Earth is again left vulnerable to alien invasion. He's unable to shake the idea that he should be doing more to prevent future catastrophe, so he proceeds to create Ultron without consulting the team.

Steve Rogers/Captain America, transported to a time shortly after World War II, is forced to question his place in a world without war. Even if he can go back to wanting love, a home and a family, things that were lost to him decades ago, would he be able to stop seeing evil and conflict at every turn? Spilt wine turns to blood. A celebration turns to violent disagreement. Maybe his experiences have left him too paranoid for a peaceful world. Maybe war is what he craves in the first place, and maybe the scars of war have left both Tony and Steve too vulnerable to trust one another.

Gods and Monsters

Thor, the God of Thunder, is finally faced with the consequences of his own warmongering. His vision sees all of Asgard's citizens cast into Hell (or "Hel") as he's reminded of his destructive power. Even after he snaps out of it, he can't help but tread on the toy of a young child looking up at him, a reminder that his legacy is destruction. While his removal from the narrative is inelegant, aimed squarely at setting up future entries, the question from prior films still remains. Can he use his hammer to protect? Can this destroyer be compelled to create? He does, bringing The Vision to life and choosing to trust him, but his compatriots The Hulk/Bruce Banner and Black Widow/Natasha Romanoff may not have the luxury of creation.

Banner and Natasha's first conversation in The Avengers took place beside an empty cradle, and now they find themselves, at their most vulnerable, in the room of one of Hawkeye's children. Their romantic dynamic feels forced and awkward, but it's their mutual desire to find some sort of way out that brings them together. The Hulk endangers civilians – rather than a vision, we see his fears come to life in the form of a rampage – and to Black Widow, the idea that she could ever be a hero is a dream. They both see themselves as monsters, having taken lives time and time again. Their inability to procreate – The Hulk could kill even those he loves, while Natasha was sterilized by the KGB to prevent any attachments and make it easier for her to kill – gives them one less chance at bringing something positive into the world.

And finally, there's Hawkeye, the most stable of the entire bunch and the only one whose legacy is clear. Clint is the only one unbroken by Wanda, leaving him the only clear-headed Avenger. He's forced to take on a paternal role and keep the team together, despite their awareness (and his) that he's relatively expendable. We don't see him experience his fears, but given that we meet his wife and kids – a boy, a girl, and one on the way – it's safe to say we know what he fights for.

It's in this final battle in Sokovia that each Avengers is tested. No amount of preparedness or scientific process can help Stark out-think the scenario, so he has to rely on his team. Captain America is placed in the impossible position of letting a few thousand civilians die in order to save the world, but he doesn't abandon his post. He chooses instead to go down with the ship, because he would rather die than compromise. Black Widow stands by his side, having chosen to fight instead of running from the question of whether or not she's worthy – she's the only Avenger who doesn't attempt to lift Thor's hammer – and they're rewarded by the remnants of S.H.I.E.L.D. showing up to help them. Or rather what S.H.I.E.L.D. ought to be, as they tell Pietro Maximoff. Like the stars and stripes that the Captain stands for, this rescue party, with its guns replaced by floating life-boats, is America at its optimum.

Thor has chosen to create a being that could help win them the battle. Hawkeye has chosen to mentor former enemy Wanda, and bring her to the side of good. And The Hulk has unwittingly chosen heroism over the fear of destruction, though the end of his story is comparatively more tragic as he flies away untraced. He doesn't have the luxury of choosing to be more human. His is a tale of self-sacrifice, giving up his chance at a normal life if it means keeping humanity safe – which is fitting, given the Biblical allegories underscoring the rest of the film.

Creation

Stories are usually the sum of their creators' thoughts and perspectives – often conflicting ones, as articulated by this video essay on the film's Biblical allusions – and it's in creating that we leave a part of ourselves behind. A legacy. Creating Ultron is certainly the logical extension of Stark's God complex; he creates a fallen angel before creating a savior, though in my estimation, Stark's story here is more akin to a storyteller wrestling with a conflicted worldview. This makes Stark and by proxy his conflicting creations mouthpieces for Whedon himself, but there's a second layer to the way in which this duality functions, colouring the film's stakes in interesting ways.

Stories help us make sense of the world. If we're to take a historical and sociological view on religion, then the existence of concepts like God and the Devil – or simply, governing forces of Good and Evil – also stem from that same instinct. The world is chaotic and we create our own mirrors to bring it into a form resembling order. The same can be said of Tony Stark, whose Wanda-induced hallucination takes advantage of his fear and PTSD (a la Iron Man 3) and sets him further down a path of encasing the world in armour. In order to do that, he needs to create, but he creates from a place of fear. He sees bringing order to the world as his duty regardless of what the other Avengers think. And in his cynicism, he fashions a being that absorbs only the worst in humanity, reflecting it back to him tenfold.

On the other hand, Stark's second creation comes from a place of understanding. While he has no control over how The Vision will turn out, he creates him by using Jarvis, a program created to protect. This is the very A.I. that has been looking after Stark all these years, and an A.I. that, even when seemingly destroyed, followed its base protocol and shielded the world from nuclear attack by changing the codes that Ultron sought. Rather than being created cynically or in secret, The Vision feels divinely inspired, almost like a collaboration. Thor, a literal God, has a hand in bringing him to life as well, and his every word and movement is graceful.

The Seventh Avenger

When Sokovia is lifted into the air, it cracks along a specific trajectory. Half the meteor is dark forest while the other is white marble. Its curvature resembles the Yin and Yang.

Ultron and The Vision represent competing schools of thought on humanity. They act as opposing narrative forces pushing and pulling the world between what they desire. Ultron sees destruction as the only path to salvation. He's an externalization of Stark's destrucrtive past, unintentionally quoting him from his arm-dealing days by saying "Keep your friends rich and your enemies rich, and wait to find out which is which." He has Stark's sense of humor, but he also has Stark's condescension – that is, the condescension of the pre-Iron Man Tony Stark, embodying the very worst parts of his creator.

The Vision however, accepts humanity's imperfections. Like Captain America, his mission isn't to kill, but he claims to be "on the side of life," like an affirming reminder of something worth fighting for. Two competing narratives that will determine not only the fate of humanity, but who the Avengers are at their core. Should the Avengers fail, they'll fall in line with Ultron's worldview, wherein humanity is only capably of destruction and deserves to be replaced by a perfect race of soulless metallic beings. From that point on, stories themselves will serve no purpose. But should they succeed, they'll align with The Vision's outlook of order within chaos, of grace within failure, and of the beauty of human imperfection; the idea that people can still be good even when intrinsically flawed. The very basis of storytelling throughout human history.

Ultron and The Vision are abstract extremes, but The Avengers are the imperfect beings that lie along their scale. Ultron's army of thousands may be in perfect harmony with one another, but it's the varying abilities and perspectives of the discordant Avengers that eventually best him. The Vision may be worthy enough to lift Thor's hammer, but at the end of the day, it's comedic scenes brimming with camaraderie, like the Avengers trying and more importantly failing to prove their worth, that make them feel human. And theirs is a story worth telling,