The Empty Man Ending Explained: From The Bridge Comes The Man

David Prior's 2020 film "The Empty Man" opens with a prologue that could easily stand alone as one of the most chilling short films ever made. It's 1995, and two couples — Paul (Aaron Poole) and Ruthie (Virginia Kull), Fiona (Jessica Matten) and Greg (Evan Jonigkeit) — are hiking through the Ura Valley in Bhutan. After crossing an old, swaying suspension bridge across a yawning chasm, Paul hears a soft sound like someone blowing into an empty bottle. Curious, he wanders off across the mountaintop in search of the source of this sound. As the others watch, he slips through an unseen hole in the rocks and disappears, as though he was never there at all.

It's another twenty minutes before the title card of the movie appears, stylized as "The Em ty Man." By this point, all of the hikers are dead except for Paul, who is trapped in a different kind of hell. The prologue eventually winds its way around to reconnect with the film's main storyline, which follows former cop James Lasombra (James Badge Dale) as he searches for the missing daughter of a friend.

"The Empty Man" was one of the many releases that fell prey to the COVID-19 pandemic, managing only a short, quiet run at the box office and skipping a theatrical run entirely in many markets. But since then the film has gathered a passionate following among horror fans. It's one of those movies that rewards a second watch, and a third, and a fourth ... the layers peeling back with each repeat viewing.

If you want to get to the heart of the horror, you could say that "The Empty Man" is a film about the terror of emptiness. And that terror comes full circle with its chilling twist ending.

The twist ending

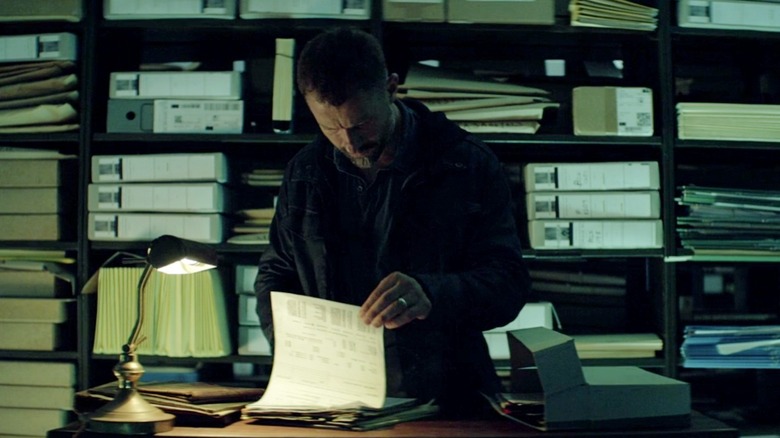

Before we take a deep dive down the rabbit hole that is "The Empty Man," let's first lay out the ending in a nutshell. James Lasombra's search for Amanda Quail (Sasha Frolova) eventually leads him to the archives of the creepy "doomsday cult" known as the Pontifex Society. Inside a box labelled "Manifestation 14" he finds a folder with his name on it, filled with details about his life. Except ... they're not about his life.

Some basic stats — his name, age, relationship status, occupation, place of birth — are written down on a piece of paper titled "Session 1." Beyond that are a collection of newspaper clippings and documents that form pieces of his identity, but they're taken from other people's lives. His doxepin prescription is written out to a patient called Alexandra Carr. There's a newspaper article about growing up in his supposed childhood home of Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco. There's an article about a "hero cop" whose family tragically died. An article about a different cop who opened up a security store after leaving the force. An article about a mother and son who died in a terrible car accident. Photos of James' wife and son that look suspiciously like stock photos. And finally, a photo of James himself, sitting naked and blank-faced in the basement of the Pontifex Institute.

As Amanda explains to him soon after, James Lasombra is a tulpa: a flesh manifestation of a person who never existed, but was cobbled together as a kind of creative group project by members of the Pontifex Institute. He is their Empty Man, a vessel created for the purpose of amplifying thoughts sent by some ancient god that lurks in the abyss.

The book that inspired The Empty Man

"The Empty Man" is loosely based on a comic book series of the same name, created by Cullen Bunn and Vanesa R. Del Rey. But while it draws some of its ideas from the comics, like the concept of thoughts spreading as a virus and a terrifying ancient god lurking beyond the veil of reality, writer/director David Prior has said that the real "touchstone" for "The Empty Man" was actually the book "Superstition," by David Ambrose. Prior told Thrillist that he previously tried to get an adaptation of "Superstition" off the ground, but it didn't work out. Instead, his fascination with the concept of a tulpa (which he first encountered in "Superstition") was incorporated into his adaptation of "The Empty Man."

"Superstition" is an existentialist horror novel. It evokes a kind of deep-seated terror in the reader that will be familiar to anyone who's read Mark Z. Danielewski's "House of Leaves." The book centers on a parapsychologist called Sam Towne, who designs an experiment in which a group of people attempt to contact a ghost using traditional methods like a ouija board. The twist? They're going to contact the ghost of a person who never existed.

Intrigued by the idea of a tulpa or thoughtform, which has its roots in Buddhist philosophy and mysticism, Sam proposes that they create a ghost. They collectively come up with a name and backstory for this ghost — an 18th century American man called Adam Wyatt who served in France under the Marquis de Lafayette — and verify that no such person ever actually existed in history. Then they attempt to contact Adam: to manifest this ghost they have invented, give him a voice, and perhaps even give him corporeal form.

(This does not end well for them.)

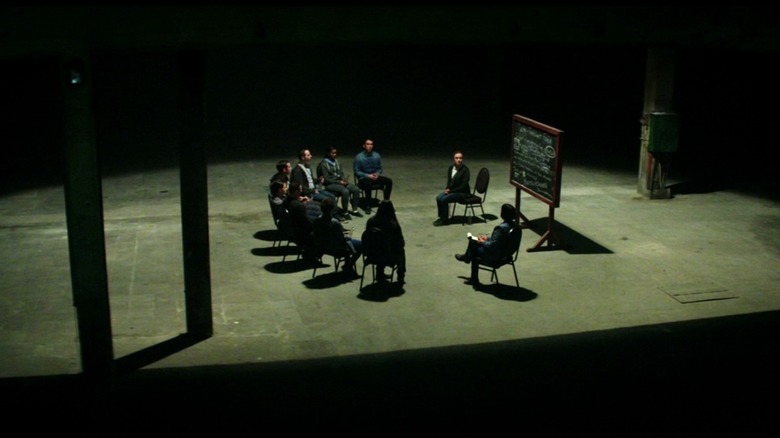

Thought plus concentration plus time equals flesh

If you're intrigued by the exact mechanics of how James Lasombra was created, then "Superstition" is the place to find answers. It almost functions as a prequel to "The Empty Man," delving into the process by which a tulpa takes form. In the book, the group meets for weekly sessions where they start by agreeing upon the basics of Adam's life, and then discuss him as though he were a real person, even speculating about the historical figures he might have met. One member of the group draws him, like a sketch artist at a police station, as the others suggest details of what he might look like. Adam quickly starts to feel real to them.

But he doesn't appear right away. He gains substance gradually. First, Adam communicates through simple knocking sounds, answering questions with one rap for 'yes' and two for 'no.'

"He knows everything we know because he's a part of us. Isn't that right, Adam?"

Two very firm raps came from the table. Everyone looked at Sam.

"It seems he has a mind of his own," Roger remarked with faint amusement. "Or thinks he has."

Next, Adam starts to spell out answers on a ouija board. Then he begins to move objects around the room. Later, he writes a phrase in the condensation on a window. But the manifestations are not confined to the sessions; as Adam grows stronger, he starts to retroactively become real. Suddenly, his name is in historical documents. His grave is discovered. He even has a direct living descendant. By manifesting him through concentrated collective thought, the group has warped the shape of the world into one where Adam actually existed.

Hindsight is 20/20

Once you know that James Lasombra was created by Amanda and other members of the Pontifex Institute, every scene in "The Empty Man" is suddenly cast in a new light. There's no better example of this than the very first conversation between James and Amanda in the movie.

On a first viewing, there's already something distinctly awkward about the exchange, but it can be written off as Amanda just being a bit of a weirdo. James is a bluntly-spoken, no-nonsense ex-cop who is perfectly familiar with woo-woo philosophy and New Age cults (he grew up in San Francisco, you know) and doesn't buy into them. Amanda, meanwhile, is dreamily opining about how she has seen the truth and the truth is that "nothing can hurt you, because nothing is real." She sounds completely brainwashed, and James' skepticism and bafflement allow him to serve as a surrogate for the audience: a bulwark against all the gibberish and woolly logic.

On a second viewing, however, this is a very different scene. This is not a teenage girl talking to a family friend about his grief. This is a member of the Pontifex Institute running diagnostics on their tulpa as he takes his first steps into the world. She truthfully tells him, "I came here to find out how you're doing," and then prompts him with details from his imagined backstory — watching him intensely as she waits for his responses, which will demonstrate whether or not his patchwork of memories has securely settled into place.

Then comes the final test. As Amanda leaves to go and see her mother, she hesitates and turns back to ask James, "Can I tell her that I saw you?" He answers, "Of course."

''Where were you?''

Even if you're onboard with the idea that the Pontifex Institute cultists just concentrated really hard on an imaginary dude until one day he popped into existence as a naked 42-year-old baby, you might still be confused about why everyone else seems to know who James Lasombra is. He has a security store with customers that he interacts with. He has a home filled with photos of himself and his late wife and son. Nora Quail (Marin Ireland) knows him, remembers their illicit funeral sex, and calls him when Amanda goes missing. Even a random cop who comes to investigate Amanda's disappearance recognizes James. "Didn't you use to be a cop?" he asks. "Yeah, I remember hearing about you."

Just as Adam Wyatt in "Superstition" begins to take root outside of the confines of the parapsychology experiment, the Pontifex Institute's efforts to create James also carve out a space for him in the world. They transmit their thoughts about him, planting memories of him in other people. They focus on James' imaginary address, an empty house, and objects manifest inside it that create the impression of a lived-in home.

But if you look closely, you'll notice things are just slightly off. Sure, James' house has the basics, but it still looks pretty bare and the backyard looks overgrown and vacant. His office has a certificate declaring his expertise in security, but there's a less obvious and very incongruous document next to it: a radiogram addressed to Amelia Earhart, a woman who famously disappeared without a trace.

James Lasombra is only a thin sketch of a person. That's why his tragic backstory is a total cliché. He's lived just enough life to have experienced "sorrow, grief, and guilt." And that pain makes him the perfect Empty Man.

What's past is prologue

The prologue of "The Empty Man" first begins to make its way back into the main story when James is doing a hardcore Google dive on the Pontifex Institute, whose Wikipedia page has a whole section titled "Ura Valley, Bhutan." Eventually we learn that Paul, the sole survivor from the prologue, was later found by members of the Pontifex Society who recognized him as their Empty Man — a kind of antennae, a bridge to the very abyss that they crave answers from. They have sustained him in his coma ever since, using him as a vessel for tuning into the ancient voices from the emptiness. Paul is the human version of an empty glass that you hold up to a wall when you want to eavesdrop on the other side. He transmits, they receive.

Paul is not a tulpa. He's an all-natural Empty Man who was born in the usual fashion. Unfortunately for the Pontifex Society, an Empty Man might only be born naturally once every thousand years. The creepy skeleton that Paul discovers after falling into the cave seems to be a shrine left over from a much, much earlier cult that formed around a previous Empty Man.

(Here's a fun detail you might have missed: The skeleton's hands and head are posed in the same manner that characters adopt when they blow into a bottle to summon the Empty Man. Later, Paul is found holding a bone flute that functions in the same way as the bottles. This implies that before Greg descended into the cave to rescue Paul, the bone flute was held in the skeleton's hands and the skeleton was blowing into it to lure Paul.)

The encounter triggers Paul's latent ability to amplify thoughts and messages from ... elsewhere. The shock of this paralyzes him, helplessly trapping him inside his own mind and body. As Amanda explains, Paul is dying because "there's only so long a human body can withstand this kind of power." Unwilling to wait a thousand years for their next prophet, the Pontifex Society set up the Scientology-esque Pontifex Institute to recruit more people, growing their collective power within the noosphere until they had enough psychic juice to brute-force a new Empty Man into existence.

''Sometimes I feel like I could just disappear and no one would notice''

Creating James might be the most spectacular magic act pulled off by the Pontifex Institute, but it isn't the only one. "The Empty Man" is just as much about disappearance, and by the end of the movie, Amanda has successfully disappeared. When James calls Nora to tell her that he's found her daughter, not only does Nora not know who he is, she also doesn't appear to recognize her own daughter's name or take any interest in the fact that Amanda has been found.

Amanda demonstrates her ability to disappear much earlier in the movie. Look closely at the scene where James visits the Pontifex Institute for the first time and you'll see that Amanda is actually in the room, out of focus in the background as Parsons says the line, "we go looking for things we have lost." Prior told Mubi that he hid Amanda among shots of the Pontifex initiates throughout the movie, driving home the idea that she doesn't need to physically hide to avoid being found. She simply erases herself from the world until not even her own mother remembers her. But erasing things like this can be as harmful as it is liberating.

The dangers of deconstruction

The Pontifex Society is rooted in the philosophy of post-structuralism, also known as deconstruction. There's even a nod to one of the founding fathers of deconstruction in the name of Amanda's school: Jacques Derrida High School. ("The high school has to be named something," David Prior told Thrillist. "You might as well name it something thematically relevant.")

As it pertains to "The Empty Man," deconstruction is the process of poking and prodding at things that are assumed to be fundamentally real, true, concrete: pulling them apart to see whether they hold up to scrutiny, or whether they're actually quite fragile. Parsons uses the example of repeating one's own name until it starts to sound like gibberish. "If profound meaning can be robbed of something by so simple a task as repetition," he posits. "Which is more fundamental? Which is more true? Your name, or the gibberish?"

This has ties to post-modernism, which asks challenging questions about entire concepts. Robert Rauschenberg's "White Painting," for example, asks the question: "What is art?" Does "art" exist outside of our collective understanding of the word and the sorts of things we associate with it?

"There's something fundamentally destructive about the post-modern project — something that's intentionally destructive," Prior explains:

"The purpose is to take social norms and cultural institutions and break them down, redefine them and hollow them out, and sometimes that needs to happen, but if you're not replacing it with something else that's equally persuasive or fundamental or important or valuable or humane or true, then it's highly dangerous. Those are some of the ideas that I was wrestling with in the film; that what I see going on around me is a lot of destruction but not a lot of refortification with anything substantial."

What's staring back from the abyss?

One detail that "The Empty Man" leaves shrouded in ambiguity is whether or not the Pontifex Institute is correct in its belief that there is something out there in the vast emptiness, something "ancient and angry," passing thoughts to them via the Empty Man. Certainly we see a very traditional scary movie monster: a spectre wrapped in dark rags that menaces Ruthie at the start of the movie, attacks Davara (Samantha Logan) at the spa, and chases James in one of the movie's climactic final sequences.

Despite their belief that nothing is real, the Pontifex Society is still searching for something. Far more frightening than a spooky rag ghost is the idea that without the meaning and structure offered by the ordinary world, however artificial it might be, there really is nothing else out there. This terror of pure nothingness is everywhere in "The Empty Man." Two major recurring motifs in the movie are bridges, structures that span lethal drops of empty air, and the empty bottles that people blow into to summon the Empty Man.

Amanda excitedly suggests to James, "What if our thoughts actually begin somewhere else, and they travel through us like signal traveling down a wire? Thoughts that are old and hidden and singular." The Pontifex Society has realized that destruction without refortification is dangerous. They've seen through the veil of reality, but they desperately need for there to be something on the other side. They're still looking for a god, for a prophet. Perhaps they created the monster that we see and the thoughts transmitted to them by the Empty Man, in the same way that they created James himself. Perhaps, like the air molecules vibrating inside the empty bottle, there's nothing in the abyss except for echoes.