The Best And Worst Moments In Nope, Ranked

Warning: This article contains major spoilers for Jordan Peele's "Nope."

It's hard to imagine anyone who had "Chris Kattan playing a monkey is a key component of Jordan Peele's new horror movie" on their bingo card. Yet there it is, more than halfway into act two of the sketch performer turned horror auteur's latest. Ricky "Jupe" Park, a former child actor played with verve and pent-up loss by Steven Yeun who details the "genius" efforts Kattan took to play Gordy, a chimpanzee and former sitcom star who brutally murdered his cast mid-taping. The moment likely alludes to this real, seminal "Saturday Night Live" sketch; Gordy's show was possibly inspired by shows such as the 1970s "Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp."

That's the secret weapon of Jordan Peele films. Every phantasmagorial element they contain is less frightening than real-life horrors, and every joke that seems a bit too absurd is rooted in real-life foolishness. Peele sees the horror in common living. He expands it to fit the silver screen. In "Nope," that means deconstructing why we must tell stories on camera and how the entertainment complex makes what should be sickening digestible. (That includes Chris Kattan's sketches.) In fairness to the underrated comedian, "Nope" throws a lot against the wall and most of it sticks with remarkable ease. The moments or elements that don't — from a mid-movie reveal to some truly deliberate pacing — are still as surprising as a "Mr. Peepers" allusion. All of it is worth discussing, so here are the best and worst moments from Jordan Peele's "Nope," ranked.

9. Best: The two opening sequences

Jordan Peele has trafficked in haunting imagery from the jump. The "Get Out" trailer sent shockwaves through the horror community and its shot of a frozen yet openly weeping Daniel Kaluuya factored into that impact immensely. The 43-year-old director's eye is impeccable. What's more, he has never struggled to open his movies. "Get Out" begins with the stunning yet funny slow-crawl abduction of Andre Logan (LaKeith Stanfield) while "Us" takes audiences into a funhouse they won't soon forget. It shouldn't be a surprise that "Nope" opens strongly, packed with idiosyncratic imagery; it still takes your breath away.

A deep-cut Bible quote, followed by the sight of a blood-covered chimp remorsefully panting on a couch while an APPLAUSE sign blinks above him. The towering presence of Keith David on a mighty steed and the sickening moment where malevolent debris from the sky strikes the character down and sends him trotting slumped into the sunset like Alan Ladd's Shane. That's how "Nope" opens. It's a dizzying rush of sights, personalities, and head-spinning events. The cumulative effect of them knocks you off balance. At this point, it's classic Jordan Peele. The opening of "Nope" delivers on the director's still-burgeoning commitment and promises audiences that they have no idea what's ahead of them. That's a promise the movie fulfills.

8. Worst: The first act's pacing

"Nope" feels deliberately paced. Its first act is all ominous allusion, buoyed by characters half in mourning and half in the horror of encroaching terrors. The second act roars to life with the arrival of a livewire tech store employee named Angel (Brandon Perea) and the goings-on at Jupiter's Claim, a tourist trap run by a former Hollywood hotshot (the previously mentioned Steven Yeun), plus a stomach-churning plot twist for the ages. The third act is a self-conscious spectacle that models its unfurling after a Steven Spielberg classic and Hollywood westerns of old. Jordan Peele knows what he's doing and he sees his vision through, but I'm not sure all of it works.

Take the first act, specifically. Peele successfully goes to painstaking efforts to establish the personalities and accumulated chips-on-shoulders of duel heroes OJ (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (a career-best Keke Palmer), the children of Keith David's fallen Otis Hayword Sr. He also sets up the film's bad miracle and a contentious but necessary relationship between OJ and Yeun's Jupe. All of that is good and essential. The issue is the opening: Peele drops the audience into two viscerally different yet equally shocking bursts of horror and violence. The film is suddenly roaring on all cylinders. In the words of "The Hateful Eight" and its lead Major Marquis Warren (Samuel L. Jackson), "Nope" suddenly slows it down. It slows it way down. The result is less a gear shift than a movie driving under the speed limit, and it arguably doesn't play.

7. Best: The alien fakeout

Jordan Peele seems keenly aware of his filmography. What's more, he's cognizant of the expectations audiences have for him, even after only two other horror films. He's releasing films in the early '20s, a time of Letterboxd reviews and Letterboxd reviews gone wrong, of incessant film dissection on Reddit threads and film Twitter accounts. Peele knows the audience is looking for callbacks; they're keen on them. So when Peele seemingly stages the reveal of his aliens and they move in the stilted, theatrical manner of the Tethered from "Us," the audience buys it instantly. This is a Peele hallmark, and it's go time.

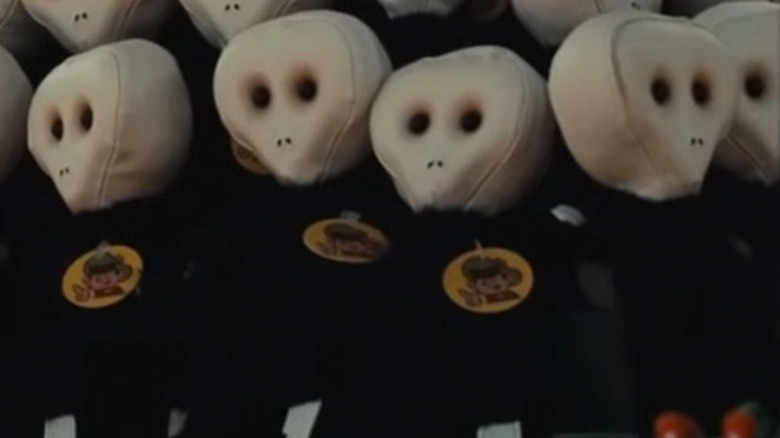

Hysterically, it isn't. Not whatsoever. The "aliens" are Jupiter's Claim workers in theatrical masks which the tourist trap has been selling (a fact that's only clear later and briefly alluded to in a background shot). But up until the sequence is purposefully drained of tension, it's terrifically tense. The "aliens" move with impish curiosity and are revealed like skin flaps unfurling, bringing the stomach-churning sense of a wound with their appearance. They feel, crucially, worthy of a big summer blockbuster. More crucially, they deflect from who and what the film's real big monster actually is.

6. Best: That reveal

Jordan Peele is not M. Night Shyamalan, even if the horror director's third movies bear remarkable similarities (aliens, an examination of miracles, the emotional fallout from a family death occurring six months before the film's main action). That said, both are adept with twists. Shyamalan made surprise reveals his bread and butter with the one-two punch of "The Sixth Sense" and "Unbreakable," and both "Get Out" and "Us" hinge on massive surprises that reframe the story preceding them. That's also so very true of "Nope."

Let's not beat around the bush: the UFO in "Nope" isn't actually a ship, but an alien creature that is eating things. It's eating horses. It's eating people. Its anger is insatiable and is, understandably, inflamed by an undigestable string of colorful pennants. If you Google "how to instill radical empathy," the first entry won't be "imagine a person or creature trying to swallow a string of those flags that you see so often at carnivals," but maybe it should be. If the previous few sentences haven't made it clear, Peele establishes the true nature of his flying object with gut-churning specificity and no shortage of gallows humor. That's what makes it excellent. The concept's uniqueness and shock value never supersede the story "Nope" is trying to tell, nor do they knock the film off-balance. If anything, they render all that has come before (and all that will come after it) absolutely inevitable. That's the best of Peele (and Shyamalan) in a nutshell.

5. Best: The Jaws of it all

"Nope" is Jordan Peele's "Jaws." There are no two ways about it. Any summer blockbuster which hinges on a primordial creature feasting on humans who don't heed the warnings of primal instincts must join the "Jaws" family tree because "Jaws" is the first summer blockbuster. "Nope" can't exist without "Jaws." Peele doesn't shy away from this. Michael Wincott's Antlers Holst is the movie's Quint, an enigmatic hunter already too close to death. Keke Palmer's Emerald gets her own, "Smile, you son of a b—h!" moment.

Peele's ability to use one of the greatest ever films as a template — and then transcend it — is part of what makes "Nope" remarkable. It gives people of color their own frighteningly specific "white whale" story. That's essential. It doesn't run back Steven Spielberg's pointed shots at capitalism so much as apply them to capitalist Hollywood specifically. The film opens with the following Bible passage: "I will cast abominable filth upon you, make you vile, and make you a spectacle." This is what Tinseltown and its cast-offs have done to both Gordy the chimp and the hungry UFO. It is no surprise they act vilely. So, yes, the "Jaws" of Jordan Peele's "Nope" is one of the film's best features. It also muddies its waters.

4. Worst: The Jaws of it all

Take Ricky "Jupe" Park and Jupiter's Claim. The Western-themed carnival that Park has taken over recently is analogous to Amity's beaches in "Jaws." Both turn profits by promising singular entertainments and relaxations. Both are under fairly new leadership. And it is the trickle-down effect of this leadership — be it that of Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) or Park — that is responsible for the carnage that follows at both locations. The mayor refuses to close the beaches despite Brody's warnings, and people get eaten. Park's commodified the feeding process of a predatory creature he cannot understand, and people get eaten. This is impeccable parallel construction.

However, in "Jaws," the mayor's designs and aims are clear and unfold in a linker fashion. In "Nope," Park's traumatic history and capitalist aims crystallize in a packed second act. They contain, I think, almost all the info a viewer needs. The details, though, are more rushed through and hard to parse than necessary. A movie shouldn't spoon-feed its audience, but Jordan Peele's admirable refusal to do so inadvertently leaves viewers either feeling stuffed with exposition or confused from a perceived lack of it. That's on top of a UFO that eats people. It's a lot. This is the blockbuster cinema equivalent of a champagne problem. That said, "Get Out" proved just how economical Peele can be as a writer. At the moment "Nope" needs to be its smoothest, it asks the audience to sift through its edges and buff things out themselves. It's a gamble, much like Jupiter's Claim, that doesn't pay off.

3. Best: The fist bump

The weekend that "Nope" was released, Jordan Peele tweeted out the intro to "Gordy's Home!" the faux-'90s sitcom that catalyzes much of the movie's tragic violence. It is appropriately grainy and obnoxiously colorful. There's something off about the whole affair. That becomes clearer when you see the show's unfortunate end in horrifying clarity. The chimpanzee who plays Gordy (also named Gordy) goes on to murder at least two of his castmates. He permanently disfigures another. When we first visit the scene of Gordy's rage, it appears surreal and possibly malicious. When the story returns to the scene under the "Gordy" title card, a more complicated picture reveals itself. Gordy has been made a spectacle. He's been run through the wringer, dismissed, and not listened to.

The extent of his healthy communication is with his young costar Ricky Park, mostly in the form of the show's signature explosive fist bumps. So when Gordy spots Park cowering under a table, it appears as though his rage will continue to manifest. Instead, Gordy seems instantly distraught. He appeals to Park in a series of howls and chatters, approaching the table and reaching out to Park for the duo's signature bump. Before Park can consummate the action, Gordy is shot dead in front of him, brains splattering across the tablecloth. At this moment, "Nope" makes a thesis memorably clear: there are animal creatures of all temperaments in the world, but Hollywood and its spectacles can make monsters of anyone.

2. Best: Hunting for the perfect shot

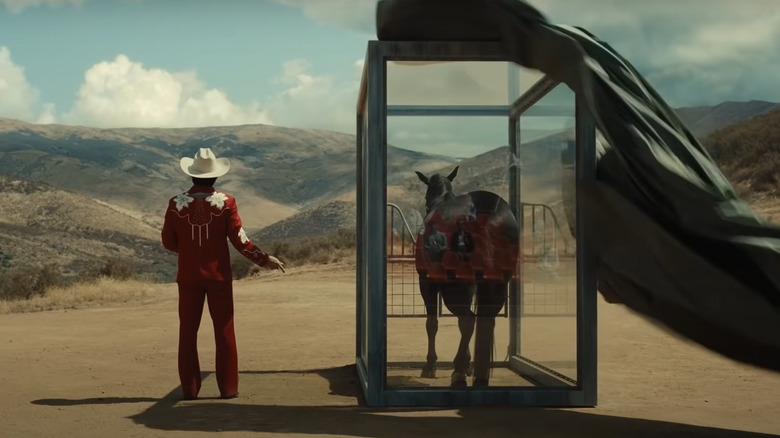

In Blake Snyder's seminal screenwriting book "Save The Cat," the "break into three" section occurs before the finale and involves "the main character choosing to try again." They've received new information. That knowledge will help them finish their journey successfully. In Jordan Peele's "Nope," the "break into three" is two pieces of technology — a vintage camera that captures images without electricity and Wacky Waving Inflatable Tube Guys. The dissonance in tone between a goofball advertising aid and equipment from the birth of movies embodies "Nope" and its contradictions. The final hunting sequence in "Nope," one that finds Emerald (Keke Palmer), OJ (Daniel Kaluuya), Angel (Brendan Perea), and Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott) pulling out all the stops to get their money shot of a hungry UFO, brings every element of "Nope" together flawlessly.

It's all there. The callbacks to tiny details. ("The Scorpion King!") Moments of filmmaking and character ingenuity, like Angel using barbed wire and a tarp to keep from being eaten, and most importantly, stretches of thrilling cinema. If you don't get chills of any degree when OJ evades the alien creature on horseback and Michael Abels' score immediately echos Hollywood western scores of old, you might need to check your pulse. Jordan Peele may be examining the dangers of how and why we make and consume spectacles, but he's also crafted one on his own terms. The final hunt makes that abundantly clear ... with one exception.

1. Worst: When TMZ shows up

Every element of "Nope" is real but heightened. It exists in a world when "The Scorpion King" is still just that, a prequel to "The Mummy" films starring Dwayne Johnson few remember fondly. Chris Kattan exists and does Saturday Night Live. It isn't surprising to think that TMZ would be around and come sniffing once the massacre at Jupiter's Claim was reported in the press. "Nope" is about how vileness and spectacle can intertwine with or birth one another. No organization has been at the heart of that issue more over the last two decades than them. Of course, they show up in "Nope." Just because they should appear, though, doesn't mean the appearance works.

When TMZ arrives in the form of a snarky, enigmatic motorcycle rider, they become a thorn in our heroes' side. Not only are they competing for the money shot, but they're also an impediment in their plan to obtain it. The TMZ journalist recklessly rides down the road in an attempt to photograph the UFO, throwing caution to the wind and putting OJ in a position where he must choose to save the man or risk losing his chance at money and the dream of a better life. That's all well and good. The issue is that, up until this point, the powers of Hollywood and tabloid journalism have affected the film but not been personified. They were scarier as faceless entities. It was more effective to see the people they impacted than they embodied. When TMZ shows up, that storytelling convention is shattered. It's a minor quibble, but a notable one given the ambitions of Jordan Peele's great movie.