Malcolm X Made History By Being The First Film To Shoot In Mecca

Spike Lee had truly established himself as a filmmaker by the time he made his 1992 biopic "Malcolm X." As one of the best-known Black filmmakers, having made five distinguished films in six years, he had pioneered new and innovative ways of presenting contemporary life among Black Americans, whether it was in creative camera moves, fourth-wall breaks, and heavy jazz on the soundtrack. "Malcolm X" needed to be something different, more restrained, something that wouldn't feature some of the provocative, regrettable scenes of Lee's earlier career.

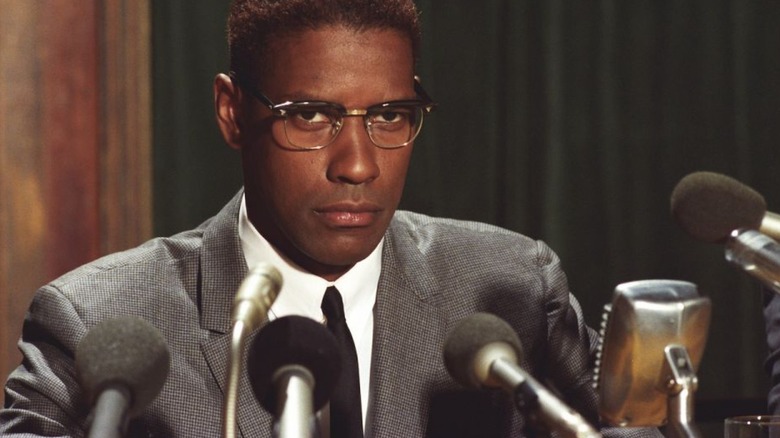

He showed new restraint in his design for the movie, a three-hour-plus epic about Malcolm X's (Denzel Washington) long, winding road from young hustler to legendary (and controversial) civil rights activist. Still, he continued to bring his own cinematic language to the movie's production, refusing to make a staid historical drama by plugging in film references (as in one shot that borrows from Lee's beloved "Ace in the Hole"), creative dance scenes, and location photography that would make history.

Because so much of the movie is concerned with Malcolm's change from criminal to a fierce warrior for the Nation of Islam, his final evolution is mostly saved for its last hour. For Malcolm X's Hajj pilgrimage to the holy city of Mecca, which saw him experience some fundamental changes in his thinking, Lee refused to settle for anything less than filming in the real Mecca. And "Malcolm X" was the first non-documentary movie to do so.

Telling Malcolm's story

The cinematic saga of Malcolm X was decades in the making, as everybody from James Baldwin (with Arnold Perl) to Charles Fuller to David Mamet wrote screenplays based on Malcolm and Alex Haley's "The Autobiography of Malcolm X." When Spike Lee came on board, he worked on the Baldwin-Perl screenplay, seeing in its sprawl and harsh truths the chance to tell a story of a personal hero for a new generation.

Lee's goal for the film was to revitalize the story of Malcolm X for a dominant culture that had been fed inaccuracies about the man. Speaking to the LA Times about the movie's potential to tell this story to a broader audience beyond that of Black Americans, Lee said that "Malcolm X ... can still be a powerful inspiration to all of those groups because here was a man who was fighting against oppression."

As David Ansen noted in a 1992 Newsweek article on one side of the movie's controversy, "many African-Americans find Malcolm's message of black self-determination more relevant than ever." Despite the fact that Lee wanted this screen version of Malcolm X to speak for oppressed people of all different stripes, his telling of the Malcolm X story was incredibly specific, true to the oppression he experienced and the journeys he took. Considering Malcolm X's faith in Islam and transformative, late-in-life pilgrimage to Mecca, Lee felt it was necessary to bring that moment to true cinematic life, and film in the holy city.

Filming in a holy city

Filming in Mecca, the birthplace of Mohammad and Islam's holiest city, had never been done before outside of a documentary context. As Spike Lee said in an interview with Cineaste, recorded in "Spike Lee: Interviews," working with the Saudi government proved a tight line to walk. "You had to have respect ... why would the Saudi government allow us to bring cameras into Mecca to shoot the holy rite of Hajj?" he asked.

Because non-Muslims weren't allowed into the city, Lee had to organize two all-Muslim units to film the Hajj scenes, one in May 1990 and the other in June 1991. That directive effectively made it so it was impossible for him to supervise the filming. According to the Cineaste interview, he was able to secure the chance to film because of Malcolm X's status as a martyr of Islam. Entertainment Weekly reported at the time that the deal was arranged through Saudi Arabia's King Fahd.

Because of the film's fragmented editing structure, and its use of voice-over to document the Hajj, it builds an impressionistic picture of Malcolm's journey, one that cuts the inspired photography captured by the film crew with close-ups of Denzel walking along the desert. It feels a bit like opening the door to something often unseen. The real footage gives us a sense of how moved this version of Malcolm X was.

That level of commitment ended up rewarding the film tremendously, turning it into one of Spike Lee's best.

Capturing faith

Even now "Malcolm X" holds up as a rich text from one of America's great filmmakers. It turns the biopic genre on its head, into an exploration of culture, values, revolution, and, yes, religion. For Spike Lee, who had used his 1989 masterpiece "Do the Right Thing" (beloved by Edward Norton and nearly everybody else) to explore the ideological divide between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., it feels like a cap on that argument. That movie was a study of racial tension in one Brooklyn neighborhood — "Malcolm X" was a study of racial constructs through history, and how one man saw in his faith an umbrella for all humanity.

As Lee's interview with Cineaste noted, some saw the Mecca scenes of the film as saccharine, and a far cry from the revolutionary Nation of Islam material that makes up most of the movie. Lee would say that "if the man says this was a deeply religious experience, you have to be true to that, no matter how you feel about religion." By filming in Mecca, Lee was certainly true to it.