Big Trouble In Little China Was Almost A Very Different Movie

Of all the movies I loved as a kid, "Big Trouble in Little China" is the one that has stuck with me the longest. The original "Star Wars" trilogy? I'm so incredibly over it, my boyhood passions deadened by the endless sequels and spinoffs. "Raiders of the Lost Ark?" Undeniably awesome, but a little too mainstream for my more cultish tastes these days.

"Big Trouble" had me hooked from the moment I first laid eyes on that brilliant poster art by Brian Bysouth. It promised action, adventure, mystery, shootouts, sorcery, kung fu, spooky locations, and a badass hero with a really cool-looking gun. The movie delivered on that promise, and then some. Eyeball monsters! Magic battles! Turf wars! The Storms! The Dragon of the Black Pool and The Hell of Upside-Down Sinners! It all fired my childhood imagination so much and I just simply ate it up.

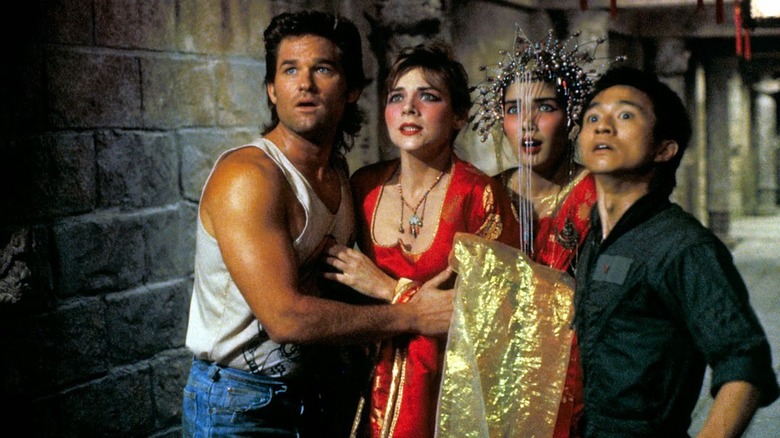

The action is set in San Francisco's Chinatown, and the film's modern setting (for the time) is crucial to the atmosphere of "Big Trouble in Little China." Our hero, Jack Burton (Kurt Russell) is an outsider perpetually bewildered by this evocative Chinese-American space thats give way to a subterranean realm of myth, magic, and ancient spirits, all illuminated with soft shades of '80s neon. With such a distinctive contemporary setting, I thought it was a joke when I first found out that "Big Trouble" was originally written as a fantasy adventure set in the Old West. That couldn't possibly work — could it?

So what happens in Big Trouble in Little China again?

When we first meet Jack Burton (Russell) he is on the road in his beloved truck, the Pork Chop Express, spouting his unique brand of philosophy into his CB radio. He's on his way to Chinatown in San Francisco where he meets up with his old friend Wang (Dennis Dun) on the eve of his fiancee Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) arriving from China.

Jack goes to the airport with Wang to pick her up, but before they get the chance, she's kidnapped by a gang of hoodlums called the Lords of Death. Chasing them to Chinatown, Jack and Wang witness a vicious turf battle between two rival factions. The violence is broken up by three supernatural entities known as the Storms, and their boss David Lo-Pan (James Hong), a 2000-year-old sorcerer who needs a girl with green eyes to break an ancient curse. Wouldn't you just know it, Miao Yin has green eyes ...

With a little help from lawyer Gracie Law (Kim Cattrall) and Egg Shen (Victor Wong), Lo Pan's old adversary, Jack and Wang must infiltrate Lo Pan's underground lair, rescue Miao Yin, and also get back the Pork Chop Express.

At the age of eight or nine, I took the movie at face value. I just thought it was about some guy getting into all these crazy supernatural adventures beneath the streets of Chinatown. Only as an adult did I realize what a clever film "Big Trouble" is, with John Carpenter and Kurt Russell deconstructing the notion of the action hero before that was even really a thing. Viewers just weren't ready for it and, like "The Thing" a few years earlier, it bombed at the box office before finding an appreciative cult audience on home rental.

The beginnings of Big Trouble

There are some fascinating bits and pieces online about the original Old West incarnation of "Big Trouble," but I wanted to find out more. So I spoke to Gary Goldman, who co-wrote the original screenplay with David Z. Weinstein, to find out how the idea came about.

Goldman studied filmmaking at UCLA and made a few documentary features before working with Louis Malle on "Pretty Baby" straight out of college, the film that gave Brook Shields her debut. He then moved into film distribution with a few friends, which was when he discovered "The Butterfly Murders." He said:

"I was starting to watch kung fu movies and samurai movies, and a little while later I was at Cannes Film Festival and there was a screening of 'The Butterfly Murders' in some back street. It totally blew me away, I'd never seen anything like it. And I thought, 'Wow, wouldn't it be great if you could do an American version of this, with Hollywood-style production values and storytelling?' It would be fantastic! So the real beginning of 'Big Trouble in Little China' was to do an American version of that kind of movie, a real mash-up of many different genres with Chinese martial arts."

After working with Larry Gordon, producer of "Die Hard," Goldman met Weinstein through friends at UCLA and decided to work on a screenplay together. They watched a lot of kung fu and samurai movies, researching for around three months before putting pen to paper. They also read up on Chinese folklore and the Tong Wars, which gave "Big Trouble" a surprising historical underpinning.

The Tong Wars in San Francisco

In the late 19th century, the Tong Wars were serious business in several major American cities. The Tongs — or "Meeting Halls" — originally started out in Chinese immigrant communities as a safe haven for Chinese workers, offering various services to people excluded from other institutions in the country. The Tongs were especially big in California as thousands of Chinese people migrated west to make a living, including working on the state's infrastructure with the railroads. Things got bad when grievances flared up between rival factions, sometimes resulting in fully-fledged gang wars (via Found SF):

For several weeks the tongs all over Chinatown have been playing war music in their rooms, and while the shrill, saw-like sound of the Chinese fiddle and the squeak of the Chinese clarinet are common sounds in the Mongolian quarter, those familiar with Chinatown and Chinese ways know that when the music continues until late in the night ... some lodge of tongs is at work offering sacrifices to the god of war and preparing to wreak vengeance upon its enemies.

The Tong Wars captured Goldman's imagination and, after talking to Weinstein, a Bay Area resident also interested in this violent phase of the city's history, decided to use it as one of the inspirations for their screenplay. Goldman continued:

"So the idea of doing a period picture evolved naturally ... our idea was not to make it contemporary. This was right after "Raiders of the Lost Ark" came out, and that's set in the '30s. We didn't think it would be a big burden, because the idea of doing a fantasy adventure period picture was possible. So the idea of doing a western wasn't that far-fetched."

The problem with Westerns

By the time Goldman and Weinstein sat down to write "Big Trouble in Little China" as a fantasy adventure set in the Old West, Westerns were deader than Butch Cassidy AND the Sundance Kid. "Heaven's Gate," Michael Cimino's monumental box office disaster, might have had something to do with that, bringing down the New Hollywood movement and making Westerns potential box office poison. Goldman and Weinstein were not phased by this, however:

"We knew at the time that Westerns were out. But we had confidence, probably more than we should have had. We felt like, yeah, it's like picking stocks. If you're a really good stock picker you buy the stock you believe in when its price is low. [Westerns] were popular for the first 100 years of cinema, so just because they've been unpopular for 10 years doesn't mean they're gonna stay unpopular forever."

They tried to be as respectful to Chinese culture as they could. Were they going for authenticity?

"We did a lot of research, but I wouldn't say ... I mean, we thought it should be as authentic as 'Raiders of the Lost Ark' is. We were reading more for inspiration, background information, and texture. The difference between our screenplay and the finished movie is all to do with tone. What we wrote was something between 'Raiders' and 'Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.' It was a little more poetic.

Although the producers bought the screenplay, they were uncomfortable with the Old West setting. After "Silverado" also flopped, the bosses decided to switch "Big Trouble" to the modern day instead, bringing in W.D. Richter ("Buckaroo Banzai") to rewrite the script.

What happened in the original Big Trouble screenplay?

The original "Big Trouble" script focused on the exploits of Wiley Prescott, a former sharpshooter in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show who is now a buffalo hunter helping feed the Chinese workers on the railroad.

Prescott is friends with Sun, a Chinese worker who has saved for a long time to bring his fiancee, Lotus, over from China. He makes the mistake of betting Wiley that he can't shoot the eyes out of a tiger painted on a kite, which the Chinese workers fly for amusement on their days off. Prescott pulls off the seemingly impossible feat, but Sun admits the money is already spent on bringing Lotus over. However, his family in San Francisco can pay the gunslinger instead.

Lotus is snatched by Lo Pan's henchmen, and Prescott scours the brothels of Chinatown, thinking the gang may have sold her into prostitution:

"Our guy walks in and he's like, 'Pour the champagne, amigos! Wiley Prescott is here!' That's how we wrote him, and Richter really pushed that blowhard style and made Jack Burton a really great character. I really love the movie, I think the dialogue is really clever and there are many great things in it, once we got used to the idea that ... instead of 'Raiders' meets 'Crouching Tiger,' it became 'Raiders' meets 'Buckaroo Banzai.'

David Lo Pan was a far more prominent figure in the original screenplay, a Chinese General betrayed by the Emperor who is cursed to roam the earth seeking the reincarnation of his true love. A prophecy tells of a woman with green eyes, something uncommon in Chinese women but far more available 2000 years later in America. That's where Jenny, the Gracie Law character in the movie, came in.

What changed in W.D. Richter's version?

Richter updated "Big Trouble" to modern day San Francisco, but as Goldman is quick to point out:

"Nothing has changed in terms of characters and plot. That's why the credit reads the way it does. It's written by David and me, and Richter gets adaptation credit, because he ... just changed it in terms of tone, time period, and dialogue. The overall tone is quite different. The movie actually plays like a parody of the screenplay we wrote."

So Wiley Prescott becomes Jack Burton, a cowboy becomes a truck driver, the railroad becomes the Pork Chop Express. One element of Burton's previous incarnation as a cowboy remains with his saddle bag and boots. The Tongs of old San Francisco become the warring factions we see during the massive street battle where Jack loses his truck.

There was a significant change to the end. In the film version, Jack avoids the usual cliche of kissing the girl and heads off into the night alone, without knowing he has an unwelcome hitchhiker hiding away in the back of the truck.

Goldman and Weinstein's version ended with the Jenny/Gracie character dying, and Wiley riding off alone to the Pacific ocean, where he hears her ghost on the wind telling him she will be with him, always.

What about the long-rumoured sequel starring Dwayne Johnson?

"Disney bought Fox, so now Disney has the rights ... I'm hopeful that Disney might say, 'Oh, this could be one of our biggest franchises, let's make ten or 100 "Big Trouble" movies, let's turn it into the Marvel Cinematic Universe.' I also think it would be interesting if they didn't want to do the same thing all over again with The Rock and maybe shot it in the Old West like we wrote it."

When I first heard about the original Old West setting for "Big Trouble," I thought the idea sounded terrible. Now I've spoken to Gary about his influences, ideas, and how his sheer enthusiasm for the project remains even 40 years later, I would really like to see how that might play out. Maybe we'll still get a chance in the future...