Year Of The Vampire: The Hunger Is A Deceptively Gorgeous Movie About Grooming

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

TRIGGER WARNING: Be advised that this article deals with issues of assault and grooming. If you are a survivor there are resources available.

The atmospheric horror thriller "The Hunger" is something of an anomaly in director Tony Scott's filmography. While the late British helmer (who cut his teeth on commercials) made a box office mint on slick action hits like "Top Gun," "Days of Thunder," and "Enemy of the State," his debut feature allowed him to sink his visual chops into the more complex world of author Whitley Strieber's vampire novel. When the resulting film was released to theaters in 1983, "The Hunger" failed to make much of a financial ($5.9 million) or critical impact (Roger Ebert called it "an agonizingly bad vampire movie, circling around an exquisitely effective sex scene").

In the ensuing years, the film has developed a cult following of fans who appreciate Scott's vampire tale for its sumptuous visuals and gorgeous cast, led by the iconic Catherine Deneuve and David Bowie as centuries-old bloodsuckers whom one might easily mistake for New Wave hipsters. Goths, in particular, gravitate towards the movie's emo vibe, which is introduced spectacularly during the strobe-y smoke-saturated opening club scene set to Bauhaus' immortal gloom ballad "Bela Lugosi's Dead." Underneath all of Scott's trademark gloss and the much-celebrated lesbian sex scene is an unusually grim movie, especially for the go-go '80s and this helmer in particular. At the center of that downbeat tone is something that many who have never seen the film before may find wildly contemporary — that the underlying subtext is about grooming.

The vampire as predator

As predatory behavior among the rich and powerful has the spotlight thrown on it more and more during the #TimesUp and #MeToo era, one of the key aspects to how people are victimized is through the process of grooming. This is essentially a stand-in word for whatever method a perpetrator of sexual violence and abuse uses to worm their way into the victim's life, be it through coercion, drugging, dependency, or simply utilizing the natural clout and charisma they have acquired to generate trust. This cycle of manipulation is often used in relation to vulnerable minors, but it can apply to adults as well, and in the context of "The Hunger" it is used on both.

Many film scholars discuss the inherent sexuality of vampirism (forms of seduction, penetrating the neck, the sapping of fluids, etc.) as if it were subtext, but that is all text. The true subtext of vampires is that love and sex are the tools they use to get what they really want: food. Vampires are inherently parasites feeding off the living, and in some cases transforming their victims into vampires themselves much the same way the abused often become abusers. The character of Miriam Blaylock (Catherine Deneuve) is no different, and something of a subversion on Tony Scott's part, in that the French actress had already become iconic as a seductress in Luis Buñuel's 1967 prostitution pic "Belle de Jour." The female vampire who uses lesbianism to lure victims who she really only sees as supper was also done to great effect previously in 1970's "The Vampire Lovers."

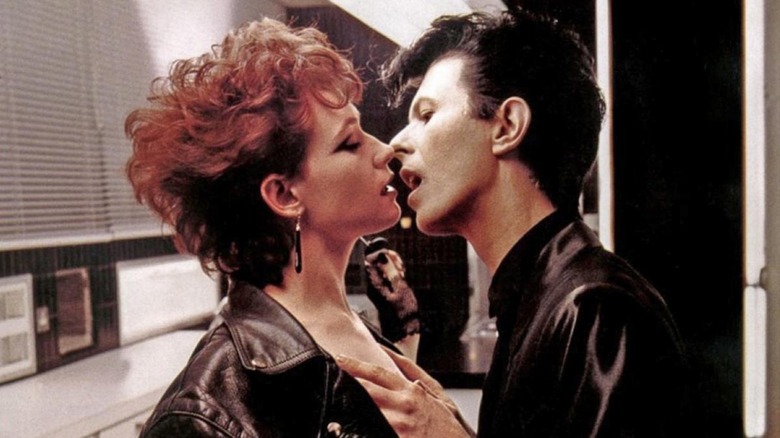

Seduction isn't really the aim of Miriam, as is made clear right from the beginning when she and her partner-in-blood-drinking John Blaylock (David Bowie) pick up a sexy couple (John Stephen Hill and Ann Magnuson) from a nightclub, primed to swing. After a very brief overture of foreplay at their castle-like abode, both Miriam and John slice their respective new partners open with identical Egyptian ankh necklaces to get at that fresh, warm red stuff inside them. Even behind the sunglasses they both wear you can sense their dead eyes as they go through the motions of "seduction," which for them is a mere form of hunting. Right from the get-go "The Hunger" makes it plain as day that these characters are predators of no redeeming value, and then goes on to elaborate on how they came to be who they are through the human character of Sarah Roberts (Susan Sarandon).

Ugly on the inside

Susan Sarandon's Dr. Sarah Roberts is a gerontologist studying the process of aging with the aim of trying to reverse it. She becomes a subject of interest for both Miriam and John, albeit for different purposes. When John suddenly realizes the eternal life granted to him by Miriam when he first became her companion (in 18th century France!) does not also extend to eternal youth, he tries to consult Sarah to stop his rapid aging. At first, he is rebuffed by her, but she soon realizes he's not a loon when John ages decades in a matter of hours. Lured into the Blaylock's world, Sarah soon encounters Miriam, who uses her charm to quickly seduce her and — in the process — infect the human woman's blood with her own, thus beginning the vampiric transformation process.

The urgency of making Sarah her companion is twofold: John has become an ancient husk of his former self, who must suffer eternally in a coffin along with all of Miriam's other former companions; also, before he completely decayed, John murdered Alice (Beth Ehlers), the teenage girl whom Miriam was already grooming to be her next partner ... once she came of age. The Blaylocks drew Alice in with the seemingly innocuous pull of playing classical music together. Like many victims of abuse, Alice is targeted/susceptible due to the neglect of her parents (her father travels to Hong Kong, her mother stays at home popping pills all day). Her relationship with the two vampires is clearly one of mutual admiration, with Alice smitten by the two's sophistication and role as surrogate parents, while Miriam appreciated the girl's youth and vitality.

John's abrupt murder of Alice was partly to see if drinking her blood could slow down his aging, but his other aim is one of mercy, i.e. to stop Miriam from putting the poor girl through the centuries of torture he will experience as an undying corpse. This is where the surface beauty of "The Hunger" gets turned on its head: Tony Scott shoots everything like a perfume commercial, with his leads all stunning physical specimens draped in couture fashion and caked in the ruby-est lipstick, but then allows legendary make-up man Dick Smith ("The Exorcist") to show how truly ugly they are on the inside, "Portrait of Dorian Gray"-style. One can't help but think of Michael Jackson, both a victim and later alleged perpetrator of abuse, whose physical appearance famously deteriorated to the point that in 2004 comedian Dave Chappelle referred to him as a "ghoulish-like creature."

A cycle perpetuated

The grooming of Alice is cut short by John, so Miriam has to race to indoctrinate Sarah, forcing the woman to kill her own jealous boyfriend Tom (Cliff De Young) with the promise that Sarah will soon forget who she was before she became a vampire. Miriam's haste shows what a truly insecure individual she is, even after existing as a vampire since the days of ancient Egypt. Her behavior is pathological: She literally cannot live one day without a companion to consume other humans alongside her in order to survive. As they say, misery loves company. At the finale of "The Hunger" Miriam's centuries of victimizing others finally come back to haunt her, with all of her mummified former companions rising out of their coffins, their arms outstretched to engulf her. It is a finale more than a little reminiscent of the infamous hallway scene in (convicted rapist) Roman Polanski's "Repulsion," which also starred Deneuve. In the end, Miriam maddeningly rots in a coffin while Sarah survives, seen in London with two young companions, a man and a woman. The cycle of grooming will indeed continue.

Audiences witnessing the permanence of what Miriam does to her companions runs counter to what many victims were taught just prior to the time the movie was made (before the anti-rape movements of the '70s), namely that it was better to cover up traumatic events like assault or abuse, to suppress it and move on with your life. Pedophilia in and of itself did not become a serious public concern until the 1980s. Nowadays the narrative has changed (albeit incrementally), and society is finally beginning to acknowledge the long-term post-traumatic harm of surviving abuse, including delayed recall. Showing Sarah on the balcony of her London flat at the end of the film (set to Franz Schubert's somber "Piano Trio in E-Flat," used previously in "Barry Lyndon") allows us to see a wistfulness, even an emptiness in her gaze. One might infer that the course of her life has been inexorably altered. Where once she was a prominent medical professional and successful writer, now she is — like Miriam — using music (a piano and cello are shown), fashion, and her feminine wiles to lure in her next attractive victims.

The profundity of this ending is somewhat tarnished by the fact that the character of Sarah was originally intended to kill herself, refusing her own transformation. This was changed last-minute to leave the door open for potential sequels, denying Sarah a level of agency. Susan Sarandon discussed this in the film's DVD commentary:

"The thing that made the film interesting to me was this question of, 'Would you want to live forever if you were an addict?' But as the film progressed, the powers that be rewrote the ending and decided that I wouldn't die, so what was the point? All the rules that we'd spent the entire film delineating, that Miriam lived forever and was indestructible, and all the people that she transformed died, and that I killed myself rather than be an addict. Suddenly I was kind of living, she was kind of half dying ... Nobody knew what was going on, and I thought that was a shame."

While the original intent may have been one thing, the resulting ending isn't a happy one, but rather an ironic one less about addiction and more of violence begetting further violence. One of the primary purposes of the horror genre as a whole is to allow people to process fear and trauma in a safe way, and Tony Scott's "The Hunger" helps us reckon with an insidious aspect of human behavior that tragically many have to carry with them eternally.