David Fincher Didn't Want Edward Norton To Let People In On Fight Club's Joke

Satire is one of the hardest forms of comedy to do, let alone do it well. If done too subtly, it can come off as thinly-veiled sincerity, with the label of "satire" becoming a bit of a smokescreen. If done too broadly, it can either miss its target entirely or rob its critical observations of their power.

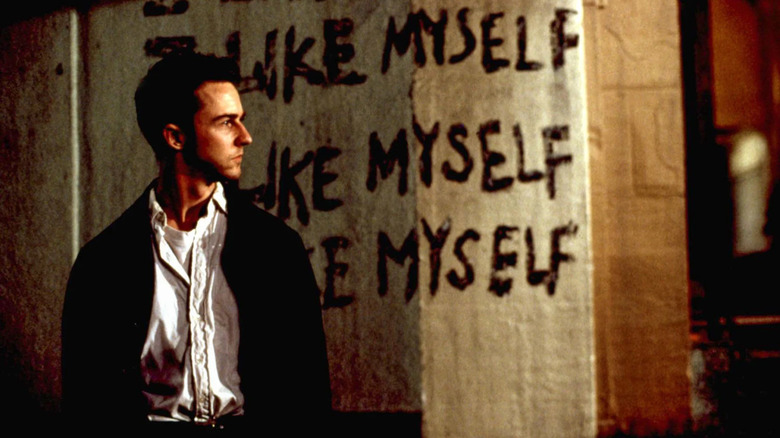

Threading the needle between mockery and sincerity is so key to making an effective and powerful satire, and that's something director David Fincher is well aware of. Since the beginning of his filmmaking career, Fincher has proven time and again to be one of the master satirists of cinema, his movies saturated with bitter, cynical irony, their moments of high drama and despair tweaked just slightly askew by the director. It's this Fincheresque tone he sought to capture in his 1999 masterwork "Fight Club," a movie so reprehensible on the surface that star Edward Norton's natural instincts were to underline the critical and comedic commentary underneath, something Fincher refused to let happen.

'We are the middle children of history'

As Fincher recalled to Brian Raftery at The Ringer (via Indiewire), he came across Chuck Palahniuk's novel "Fight Club" at just the right time in his life: "I was in my late thirties, and I saw that book as a rallying cry," he explained, finding that Palahniuk's book "was talking about a very specific kind of anger." Producer Céan Chaffin observed Fincher's reaction to the book firsthand: "I remember him reading it in galley form and laughing the whole time."

Fincher brought his most subversive instincts to bear on the material right from the pitch meeting, going to studio 20th Century Fox and presenting them with the choice to either "do the $3 million version of this movie and make it on videotape," or commit a real "act of sedition" and "put movie stars in it and get people to go and talk about the anti-consumerist rantings of a schizophrenic madman." Fincher was given the go-ahead to develop a script, eventually ending up working with Jim Uhls, who wrote the script that Fox greenlit. The director made his intended tone explicit up front, explaining how "we were making a satire. We were saying 'This is as serious about blowing up buildings as 'The Graduate' is about f—ing your mom's friend.'"

Ironically, before the script ended up with Uhls, the book was sent to "The Graduate" screenwriter Buck Henry, in the spirit of Fincher's satirical model for his approach. According to the director, Henry declined by simply saying "I don't think there's anything funny about it."

Fincher's special brand of humor

Initially, Fincher and Norton were on the same page when it came to adapting "Fight Club" to the screen. After reading the book and finding it "sardonic and hilarious," Norton asked Fincher "you're going to do this as a comedy, right?," to which he says the director replied "'oh, yeah — that's the whole point.'"

Yet, as shooting on the film began, the director and star's opinions on just what kind of a comedy "Fight Club" was began to clash. As Fincher recalled, "Edward had this idea of, 'Let's just make sure people realize that this is a comedy,'" and the two debated the film's tone "ad nauseum." On Fincher's part, he wanted to draw the line between approaches, explaining how "there's humor that's obsequious, that's saying, 'Wink-wink, don't worry, it's all in good fun.' And my whole thing was to not wink." Fincher's aggressive, gadfly-like ethos was to take the movie and have people confused whether the filmmakers were on the level or not.

Although that intentional confusion over the film's tone led to long debates on set and numerous takes to be filmed, Fincher and Norton eventually found an equilibrium. As Norton recalled, "I was doing something in one of those office [scenes], and I looked at Fincher, like, 'Is this what you're thinking?' And he goes, 'A little less Jerry, a little more Dean.' And I knew exactly what he meant." Thanks to the director and star finally seeing eye-to-eye, "Fight Club's" special blend of satire was achieved.

'Let's evolve, let the chips fall where they may': Fight Club's reception

One of the many virtues of Fincher as a filmmaker is the trust he puts in his audiences. As editor Jim Haygood observed while editing "Fight Club," "David's thing is 'You've got to assume that people are smart — you want them in on it.'" Thanks to this ethos, "Fight Club" is not a movie that panders to the viewer, with both its twisty narrative and subtextual satire dropped into the laps of the audience as opposed to being spoon-fed to them.

That approach became dangerous to the film in a number of ways. As producer Bill Mechanic said upon viewing the finished movie, "anything that makes you this uneasy is great," but selling it was going to be "a knockdown battle." In a year that included the likes of the Columbine mass shooting and the rioting at Woodstock '99, "Fight Club" didn't just seem distasteful, but borderline irresponsible when taken at face value.

"Fight Club's" reception ever since its release in October of 1999 has been decidedly mixed. Not just in terms of raves or pans, either — the phenomenon of men idolizing Tyler Durden and other such characters is a media literacy issue that persists to this day. Norton believes that most of "Fight Club's" critics "missed the satirical edge of it ... with 'Fight Club,' you have to feel threatened by what it's saying to think it's an authentically nihilistic movie. And if you relate to what it's saying, you think it's a comedy." While the movie's virtues and sins are still being debated, in a world where corporate brands tweet like they're people and toxic masculinity continues to run rampant, it's safe to say we're all a little bit more in on the film's joke.