Disney's The Little Mermaid Made Some Drastic Changes To The Dark Fairytale

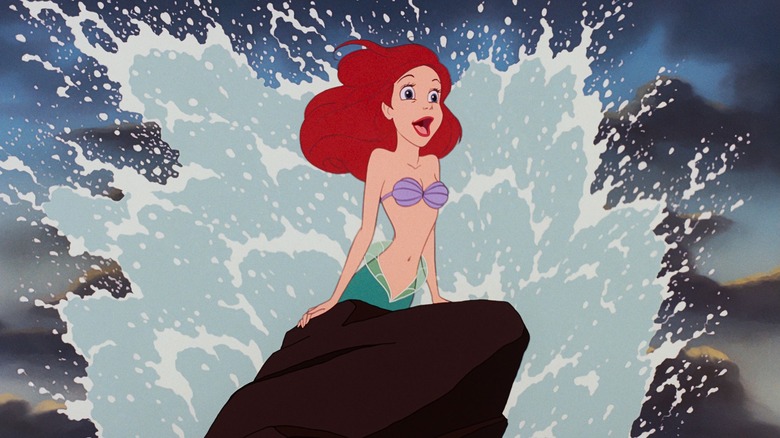

Released in 1989, "The Little Mermaid" kicked off the Disney Renaissance and is still considered by many to be one of the Mouse House's finest achievements. It may be a Disney classic, but it's not exactly a faithful retelling of Danish author Hans Christian Andersen's famous 1837 story. I loved Andersen's often tragic brand of fairytales as a child, and "The Little Mermaid" was a favorite. Aside from that, I used to watch the 1975 anime version on TV, which hews much closer to the source material. I still remember feeling deeply confused as a kid when I watched Disney's adaptation for the first time.

I might not be the biggest fan of musical theater, but there are some iconic Disney songs that you simply can't mess with. From "When You Wish Upon a Star" to "Once Upon a Dream" to "He's a Tramp" to "Cruella De Vil," the Mouse House excels in this area and always has. "The Little Mermaid" is no exception. With compositions written by Alan Menken and lyrics by the late Howard Ashman, the movie includes unforgettable songs like "Part of Your World," "Under the Sea," and "Poor Unfortunate Souls."

While Andersen's original tale was obviously not a musical, music still played a role in the story. Though the mermaid had an incredible singing voice, the prince was never able to hear it, since the sea witch took it from her. While that is similar to what happens in the Disney movie, much of the story is different. With a live-action adaptation headed to theaters in 2023, let's discuss what major changes Disney made to Andersen's "The Little Mermaid."

Being human is painful

While much of the beginning of Disney's "The Little Mermaid" unfolds similarly to Andersen's tale, there are some notable differences even before the drastically-altered ending. The mermaid does indeed trade her voice for legs in order to spend time with the prince she rescued — though the sea witch cuts out her tongue to do it. However, the mermaid's time as a human is excruciatingly painful. Every single step she takes feels "as if treading upon the points of needles or sharp knives." Despite this, the mermaid bears the pain willingly because she loves the prince so much. Sadly, he treats her more as a pet than a princess, even having her sleep at his door on a velvet cushion.

The bargain that the mermaid forges with the witch is different as well. She must make the prince not only fall in love with her, but marry her so that she may gain an immortal soul — something mermaids do not possess. Because of this, when mermaids die, they transform into sea foam, though they typically live for hundreds of years before that happens. If she fails in her mission, this end would befall the mermaid far sooner. Another interesting tidbit from Andersen's story: "Mermaids have no tears, and therefore they suffer more." Even more heartbreaking: the prince loves the girl he thinks is responsible for saving him and of course, the mermaid has no way to explain that it was actually her.

Happily ever after?

Unlike Disney's story, which ends with a signature Mouse House "happily ever after," the mermaid of Andersen's tale does not succeed and the prince marries another. Ever a class act, he says to the mermaid, "You will rejoice at my happiness; for your devotion to me is great and sincere." Her devotion to him was great indeed, as her sisters traded their hair to the sea witch in exchange for a way to get the mermaid out of her bargain, yet she could not do what was required. The mermaid would have to kill the prince, stabbing him in the heart with the knife she was given, so that the blood would fall on her feet, making them grow into a tail once more.

Rather than kill the prince, the mermaid threw herself into the sea and waited for her body to transform into foam. Though she did become one with the ocean, her fate was not as simple as becoming the foam cresting the waves. Her unwillingness to kill the prince to end her own suffering led to her acceptance by the daughters of the air, who basically earn their immortal souls by doing good deeds for mankind for 300 years. The news causes the mermaid to cry for the first time in her life. So, the story pretty much ends with her in purgatory, but with the hope of redemption. Like some of Andersen's other famous tales, this could be classified as something of a "happily ever after," though it's a far cry from Disney's happy ending to "The Little Mermaid."

The evolution of fairytales

Even as someone who grew up loving the animated features of the Mouse House, it's easy to admit that Disney sanitizes these stories. You could argue that in their purest forms, fairytales aren't meant to be consumed by children. Consider early versions of "Little Red Riding Hood," in which she unwittingly cannibalizes her grandmother before climbing into bed naked next to the Big Bad Wolf. This is just one example, but there is plenty of nightmare fuel to be found in the earlier iterations of these tales.

While some of the fairytales we still read today can be traced back thousands of years, so many of these stories were originally intended for adults. A lot of these folktales began as a fun way for women to pass the time while pushing back on a society that relegated them to side characters in their own real-life stories. However, over time, these tales instead became a way men could teach lessons to children, often young girls. The phrase "fairytale" was actually coined by French writer Madame d'Aulnoy in the 17th century. Although her stories aren't what you'd consider kid-friendly, she's one of the most important figures of the genre.

Much of what we know of modern fairytales as children's literature began with French author Charles Perrault in the late 1600s. In fact, making these stories suitable for children is hardly a practice that began with the Mouse House, but probably most famously with German folklorists, the Brothers Grimm. Jacob and Wilhelm's versions may be chockfull of sex and violence by today's standards, but compared to earlier iterations of the stories, they were downright tame. Even still, kids today would likely be horrified to see Cinderella's stepsisters cut off bits of their feet to fit into the gold slipper or Snow White's wicked queen forced to dance in red-hot iron shoes until she dies.

Perhaps every generation is more careful with their kids than the one before. I know children growing up now aren't generally watching animated movies as harrowing as those I watched in my youth, like "Watership Down" or "The Last Unicorn" — not that either of those were originally intended for kids either. "The Little Mermaid" was indeed written for children, but the guy who penned "The Red Shoes" and my other childhood favorite, "The Little Match Girl," had quite different ideas on storytelling from Disney.