Every Batman Movie And The Real-World Fears They Highlight

Every era in history sees people become preoccupied with specific societal concerns, and fictional characters — including Batman and his adversaries — are often created to address certain broader societal issues. If those characters endure through enough successive historic eras, their stories can serve as a Rosetta Stone of what our most prevalent real-world fears were through each of these moments in time.

Whatever the politics, bigotries, or neuroses of a given historic period, and however serious or lighthearted any film depicting the Dark Knight might be, the odds remain better than average that Batman's previously confident beliefs are being challenged by Catwoman's "subversive" worldviews, his criminal interrogation techniques are unlikely to satisfy the ACLU, and he's found himself stuck with a bomb that he's struggling to get rid of.

Here are the real-world fears that Batman has helped us face over the past several decades of live-action films (apologies, "Batman: Mask of the Phantasm").

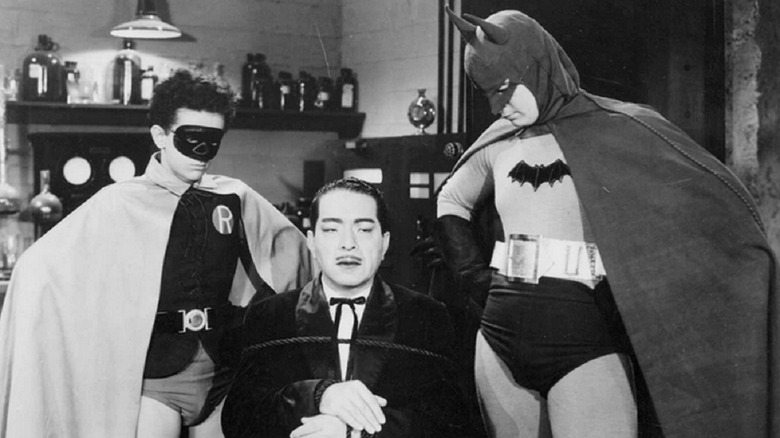

Batman (1943) & Batman and Robin (1949)

Few fans recall Batman's first big-screen appearance in Columbia Pictures' 15-chapter serial in 1943, which featured the first appearances of the Batcave and the trim, mustachioed version of Alfred, versus the portly buffoon who'd appeared in the comics.

In the "Batman" serial, both Batman and Robin are government agents who, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, become aware of a Japanese espionage and sabotage ring, led by Dr. Tito Daka, a prince in the same Imperial House of Japan as Hirohito and an agent of the Japanese government.

Daka has no direct antecedent in the comics, although "Detective Comics" did feature appearances by fellow "Yellow Peril" villains Fui Onyui from 1937-38, including the title's first-issue cover, and Fu Manchu from 1938-39. Daka is a mad scientist who recruits a fifth column of American businessmen, known as "The League of the New Order," reflecting World War II-era concerns over enemy collaborators. He also creates a mind-controlling "Electrical Brain," indicating America's emerging fears of its self-perceived scientific gap with Germany, Japan, and eventually Russia.

The first "Batman" serial proved commercially successful enough for Columbia to release the 15-chapter "Batman and Robin" in 1949, whose villain is able to remote-control cars during the post-WWII boom in automobile production. "Freeways" were introduced to our lexicon in 1930 by Edward Bassett, the pioneer of modern urban planning, and cars' growing prominence would cause President Eisenhower to sign the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 into law.

Batman: The Movie (1966)

The 1966-68 "Batman" TV series was already haunted by the rise of youth counterculture during the Vietnam War, with Gotham's cops cast as squares old enough to have served in WWII or the Korean War. Batman's colorfully costumed villains came across as Andy Warhol-esque pop artists, whose henchmen often resembled hippies, beatniks, mods, and go-go dancers.

But 1966's "Batman: The Movie" explicitly tackles the Cold War, with the Penguin's war-surplus submarine firing what Robin identifies as a Polaris missile, four years after the Cuban Missile Crisis. Catwoman both woos and breaks Bruce Wayne's heart by posing as a Soviet journalist.

Van Williams even voices an unseen, glory-hounding U.S. president, whose Texas accent recalls Lyndon B. Johnson. Between the Pentagon not seeing through the Penguin's alias of "P. En Guin" when he purchases a submarine, and the squabbling of the "United World Organization's" (United Nations) Security Council, it's the adult authority figures who come in for a drubbing in this film.

The movie ends with the dehydrated, intermingled dust of the Security Council members reconstituted and alive, but each speaking languages, and exhibiting national stereotypes, other than their own. Batman muses "this strange mixing of minds" might do more good than harm, before the final title card transitions from "The End" to "The Living End?"

With the Space Race escalating America's fears of being outpaced technologically, 1966 also saw the Batcave gain a nuclear reactor and "Batcomputer," as Batman's gadgetry expanded to include Shark Repellent Bat-Spray.

Batman (1989)

The 1966-68 "Batman" TV show made light of how Gotham was meant to be New York City, but director Tim Burton's first "Batman" film in 1989 cast an Ed Koch lookalike to play Gotham's Mayor Borg, a character who didn't exist in the comics. Koch was elected mayor of New York City in 1978, three years after President Ford's denial of a federal bailout to the nearly bankrupt NYC led to the New York Daily News' "Ford to City: Drop Dead" headline.

Perceptions of the city as a crime-ridden cesspool persisted through the end of Koch's tenure in 1989 when the murder rate did indeed reach a historical high. The first paragraph of Sam Hamm's script described Gotham "as if Hell erupted through the sidewalks and kept on growing," and its boogeymen were the stereotypes of New York City crime through the 1970s-80s.

Pinstriped mafiosos from the '70s "Godfather" films bossed around multiracial gangs from the '80s "Death Wish" films, as squalid muggers preyed upon clean-cut out-of-town tourists in the first few minutes of Burton's "Batman."

Jack Nicholson's Joker begins as a dapper, unbalanced gangster, but his high dive into industrial chemicals — during a decade where concerns with toxic waste gave us 1984's "The Toxic Avenger" and "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" — transforms him into a terrifyingly ingenious and remorseless "superpredator," to borrow the term criminologist and political scientist John J. DiIulio Jr. used for the since-discredited concept he foisted upon real-world law enforcement in the 1990s.

Batman Returns (1992)

Unsurprisingly, this sequel continues themes from Tim Burton's first "Batman" film, including its depiction of urban decay through Gotham City's gothic decrepitude, as early '90s pop culture made a show of atoning for the sins of the '80s.

Burton made a gag out of TV news anchors looking ragged because they were forced to abstain from Joker-poisoned cosmetics and hygiene products in 1989's "Batman." He expands this anti-consumerist messaging in 1992's "Batman Returns," as Selina Kyle makes her debut as Catwoman by destroying the well-stocked department store owned by her boss, Max Shreck.

Shreck attempted to murder Selina in his office, but what finally triggered her fury was hearing a voicemail ad for Shreck's "Gotham Lady Perfume" on her home phone immediately afterward. Shreck is practically the ultimate 1980s-90s movie villain, as a corporate raider, slumlord, polluter, and sexual predator, whose physical intimidation of Selina, while she's still his mousy secretary, plays like a precursor to the #MeToo movement.

As Selina gains ownership of herself, she pushes Bruce Wayne to evolve beyond his extended pre-adolescence — well after the phrase "Peter Pan Syndrome" entered popular parlance in 1983 — so when he searches for Selina at the end, it's as Bruce, not Batman.

The gulf between rich and poor is underscored by the deformed Penguin, walking proof of the sins of the privileged, growing inhumane after being abandoned by his wealthy parents. His plot to murder all of Gotham's firstborn sons plays into America's child abduction and endangerment panic from the 1970s-80s.

Batman Forever (1995) & Batman & Robin (1997)

Warner Bros. replaced Tim Burton with director Joel Schumacher after "Batman Returns" drew letters from angry parents that made McDonald's squeamish about its Happy Meal and collector's cup tie-ins to the film. But Schumacher faced his own backlash when the redesigned Batsuit in 1995's "Batman Forever" was compounded by the Dynamic Duo's butt-shots in 1997's "Batman & Robin."

"Batman & Robin" vigilantly avoided alluding to potentially divisive real-world problems, beyond reducing Poison Ivy to a strawman of cartoonishly extremist environmentalism, who seeks to wreak "Gaia's Vengeance" upon humanity. (Poison Ivy and Batgirl's depictions were already slightly gynophobic.)

By contrast, the origins of "Batman Forever" as a self-consciously consumer-friendly product ironically made its messaging even more anti-consumerist than Burton's "Batman" films. The Riddler invents "The Box," which broadcasts 3D TV images directly into viewers' brains, but also siphons off their brainwaves to be absorbed by the villain.

When "The Box" becomes ubiquitous in Gotham's households, one newsreader reports: "Critics have claimed 'The Box' turns Gothamites into zombies, but Edward Nygma just shrugs: 'That's what they said when TV was invented.'"

Both the Riddler and Two-Face take seriously the showmanship of their roles, with Two-Face donning a circus ringmaster's outfit to conduct the attempted bombing that orphans Robin, which inspires Edward Nygma to brainstorm a succession of costumed aliases that culminates with "The Riddler." The Riddler speaks the mass-media patois of game shows and spectator sports, and critiques Two-Face on the audience engagement of his presentation.

Batman Begins (2005)

Just as Tim Burton's "Batman" was born in the long shadows of New York City's 1970s-80s crime wave, so are each of the three films in director Christopher Nolan's "The Dark Knight Trilogy" reacting to different aspects of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks' aftermath.

The mobsters and crooked cops of 1989's "Batman" are still present at the outset of 2005's "Batman Begins," but traditional organized crime, as represented by boss Carmine Falcone, is soon supplanted by the ideologically driven terrorism of Dr. Jonathan Crane as the Scarecrow. The villain weaponizes a combination of hazardous chemical agents and unsecured urban infrastructure against the city's civilian population.

The post-9/11 metaphors become more explicit with Ra's al Ghul, leader of the League of Shadows. The film's co-writer, David S. Goyer, told Creative Screenwriting magazine, "We modeled him after Osama bin Laden," making his League of Shadows a less Middle Eastern al-Qaeda.

Irish actor Liam Neeson was cast to play Ra's al Ghul's French alias, Henri Ducard, who recruits Bruce into the League in Bhutan. In spite of this mix of European and Asian influences, the character retained his Arabic name from the comics, which translates to "Head of the Demon."

And just as post-9/11 conspiracy theories afford comfort by connecting the dots of a chaotic reality, Nolan cast the League as a singular culprit behind multiple historical upheavals: from the fall of Rome to the Black Plague's spread and even to the endemic crime of Gotham that killed Bruce Wayne's parents.

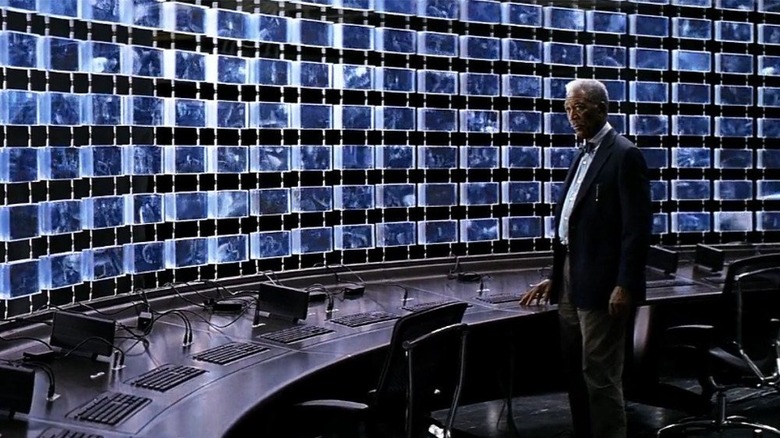

The Dark Knight (2008)

When the Joker (recast here as a domestic terrorist) steals from Gotham's gangs, the city's Italian, Black, and Chechen mob bosses agree to allow their Hong Kong accountant to hide their remaining funds, beyond the reach of both the Joker and Batman. Batman responds with "escalation" — ignoring international extradition laws to kidnap the accountant — which returning storyteller David S. Goyer deemed the sequel's biggest theme.

Bruce escalates further by tasking Wayne Enterprises CEO Lucius Fox with utilizing a mass surveillance system, using Gotham citizens' own mobile phone technology to spy on them; many pundits saw it as Christopher Nolan's commentary on President George W. Bush's approach to the "War on Terror."

In The Wall Street Journal, Andrew Klavan supported what he perceived as the film's endorsement of Batman's (and Bush's) extreme measures, arguing they have "to push the boundaries of civil rights to deal with an emergency, certain (they) will re-establish those boundaries when the emergency is past."

Cosmo Landesman's contrasting review for The Sunday Times condemned the film for "champion(ing) the anti-war coalition's claim that, in having a war on terror, you create the conditions for more terror." President Obama even used the film to justify America's fight against the Islamic State, which he likened to the Joker because both have "the capacity to set the whole region on fire."

Fans theorized the Joker, who repeatedly offers differing origin stories for his scars, was a war-wounded veteran with PTSD, which Patton Oswalt promoted and expanded upon.

The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

Bane was born in prison in the comics, and his takeover of Gotham City checks off a list of conservative fears about a domestic terrorist and/or foreign national takeover of America, as he isolates law enforcement without aid, blows up the city's professional sports stadium, separates Gotham from the rest of the United States, executes the head of its elected government, discredits one of its most respected authority figures, and releases its prisoners into the public after crashing the city's stock exchange.

Bane then institutes martial law — enforced by an armed neutron bomb, to hold the populace hostage — and a kangaroo court so his fellow terrorist, the Scarecrow, can pass judgment over the former elites of what remains of society. The Wall Street Journal and Entertainment Weekly spotted signs of a possible "Occupy Gotham" movement in the film's trailer, in which Selina Kyle remonstrated with Bruce Wayne for "liv(ing) so large, and leav(ing) so little for the rest of us."

Salon's progressive David Sirota characterized the full, completed film as a "backlash" to the "Occupy Wall Street zeitgeist," while conservative comics writer Chuck Dixon, who co-created Bane, described him as "far more akin to an Occupy Wall Street type if you're looking to cast him politically."

However, Christopher Nolan denied intending any anti-Occupy or other political commentary in his "Batman" films. David S. Goyer chalked up any similarities to Occupy to a lucky coincidence, after rumors of filming in Zuccotti Park, during the movement's protests, failed to transpire.

Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016)

Director Zack Snyder and returning co-screenwriter David S. Goyer revisited their climactic Superman versus Zod fight in Metropolis from 2013's "Man of Steel" by providing a ground-level perspective on that unnatural disaster in 2016's "Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice."

John Beifuss' review for The Commercial Appeal describes how Bruce Wayne "witnesses the collapse of one of his corporate skyscrapers, Wayne Tower, in a special effect of pancaking architecture and blossoming ash clearly designed to suggest the fall of a Twin Tower."

As a U.S. Senate subcommittee calls on Superman to account for such collateral damage, protestors outside the Capitol brandish picket signs reading: "Tell Us The Truth About Aliens," "Superman = Illegal Alien," "This Is Our World, Not Yours," "Aliens Doom Nations," "Earth Belongs To Humans," and "God Hates Aliens."

As such, Kaleem Aftab wrote for Vice that not only was "Batman v Superman" intended to critique "the popular reaction to 9/11," but Superman's cross-cultural experiences in that film were comparable to Aftab's own as a Muslim in America. Aftab credited "Dawn of Justice" with delivering "a condemnation of what America is becoming, a place where immigrants, especially those unfairly tainted because of the mass destruction caused by a few, are no longer part of a viable American dream."

Just as the battle of Metropolis made Bruce Wayne see Superman as an existential threat to humanity, Batman's brutal treatment of criminals inspires Clark Kent to expose him through The Daily Planet.

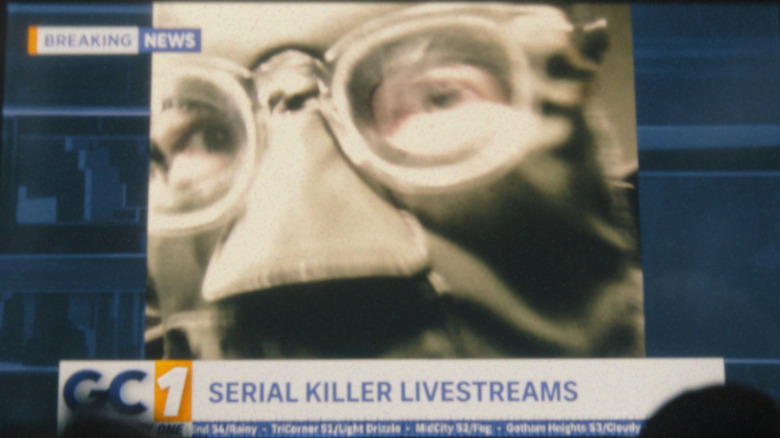

The Batman (2022)

Writer-director Matt Reeves' "The Batman" parades familiar fears from previous "Batman" films, but with updates. The mobsters and crooked cops of 1989's "Batman," 2005's "Batman Begins," and 2008's "The Dark Knight" are showcased yet again, for example, but are joined by corrupt city officials, ranging from the mayor to the district attorney.

In terms of revealing the darker truths behind the facades of historic civic heroes, 2008's "The Dark Knight" and 2012's "The Dark Knight Rises" featured the coverup and exposure of Harvey Dent's sins as Two-Face. The 2022 film saw Bruce confronted with the secrets kept by the Wayne and Arkham families, including the true nature of his father's connection to mob boss Carmine Falcone.

Furthermore, the Scarecrow exploited the infrastructure of Gotham's water supply for terrorist purposes in "Batman Begins," but the Riddler's bombing of Gotham's seawall in "The Batman" opened the city to flooding, long after climate change had been proven to help accelerate rising sea levels. Reeves also micro-engineers class conflicts by establishing Batman, Catwoman, and the Riddler are all orphans, but each turned out differently partly due to their respective economic backgrounds.

While other Batman villains have been recast as terrorists or serial killers, Reeves' Riddler is explicitly both. The character was inspired by the costume, insignia, and ciphers of the Zodiac Killer of 1968-69, while his crowdsourced crimes recall the conspiracy cult of QAnon.

"The Batman" even calls out its hero for inspiring more extreme acts of "vengeance" than his own, as he realizes he needs to offer hope as well by the end of his journey in the movie.