The 15 Best Kung Fu Movies Ranked

Let's start by defining terms: "The Karate Kid" is not quite a kung fu movie. "Bloodsport" is closer, but as great as Jean-Claude Van Damme was in his oiled-up wheel-kicking prime he doesn't really know kung fu. Specifically, the kung fu genre is all about elaborate and blindingly fast fight choreography that derives from Chinese "Wuxia" films. This art form began in the 1920s on mainland China, though the oldest extant films like "Story of Huang Feihong" date to the 1940s. The genre combines the vivid theatricality of Chinese opera with the folk adventures of Wuxia novels, often set in sweeping feudal lands where a lone sword-wielding protagonist embarks on a grand heroic adventure.

Wuxia was banned in mainland China for decades for promoting "superstition and unscientific thinking," according to "Chinese Martial Arts Cinema." Production was moved to Hong Kong, where the genre thrived in the 1960s and '70s inside the Shaw Brothers studios, producing seminal works like "The Five Deadly Venoms" and "The 36th Chamber of Shaolin," both in 1978. These colorful epic fighting dramas are full of goofy gags, silly wigs, and crucially, intricate combat choreography that sprawls all over the elaborate sets. Wuxia has evolved over the years to include modern crime plots, but what must remain is the balletic battles that lean on centuries of theatrical Chinese martial arts traditions. Here are the 15 best kung fu movies, ranked

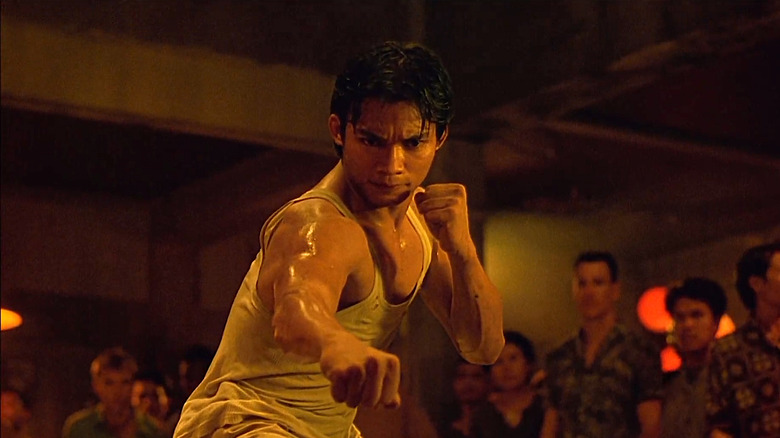

15. Ong-Bak (2003)

"Ong-Bak: Muay Thai Warrior" (2003) is modern low-budget filmmaking at its grainy best. Art can really thrive when the artist is forced to compromise, and with a paltry $1.1 million budget "Ong-Bak" delivers kung fu nirvana. That cash also goes a lot farther in director Prachya Pinkaew's native Thailand, but it still demanded a stripped-down approach. Tony Jaa plays said warrior, and his athletic ability is the special effect that allows this movie to diverge from the wire-fu, bullet-time operatics that eventually became an eye-roll four years after "The Matrix."

"Ong-Bak" is really a throwback to early 90's martial arts melodramas. When a small village's sacred "Ong-Bak" statue is stolen, the farmers send their prodigal Thai-fighting son to recover it. A trek to the big city and an underground fight tournament ensues. "Ong-bak" borrows a lot from "Kickboxer," as well as another underrated Jean Claude Van-Damme classic "Lionheart." Tony Jaa's kung fu is also more akin to Van-Damme's high-kicking balletics than the grounded bullishness of real-world Muay Thai. Jaa long studied his nation's native discipline but adopts Thai-style knee-strikes, aggression, and cage-craft (cutting off an opponent's movements) into an elevated action-movie form that spawned two prequels in this rib-shattering throwback franchise. Unlike the inherently cinematic Wing Chun of Donnie Yen or Jet Li — which has little relation to real combat — Tony Jaa's Muay Thai is UFC-proven, and that brutal realism sets this B-movie gem apart from the pack.

14. The Raid: Redemption (2011)

"The Raid: Redemption" is the only Indonesian entry here and made a big splash for its unflinching action in 2011. It's got all the shaky-cam cinematographic flair of an episode of "CSI," but the simple filmmaking is a nice counter to the extravagance of near-contemporary modern martial arts films which (like 2013's "The Grandmaster") can veer into stylish self-satire.

"The Raid" has no such pretenses. The cinematography has the same depth of field as the straight-forward plot. It follows a SWAT team who breaches a gang lord's apartment building compound. When it turns out this villain's tenants are all machete-wielding assassins, the well-armored hunters quickly become the hunted. Like in "John Wick," the heavy weaponry threatens to steal the show but things really get good when the ammo runs low and the close-quarters kung fu kicks in. You'd hate to be a stunt man working with SWAT team leader and star Iko Uwais. This man pulls no punches in this film's inventively graphic and convincing hand-to-hand fights scenes.

13. Fearless (2006)

In the early 2000s, China was pushing to have "Wushu" (which translates to "martial arts") added to the Olympics. The 19th-century kung fu story of "Fearless" opens with a vignette of a modern Chinese official (Michele Yeoh) passionately advocating for this position, and this fighting story starring Jet Li is the pitch. Unlike some of the troubling aspects of Li's propagandistic film "Hero," the Chinese perspective in "Fearless" is in the competitive spirit of nationalistic sports rivalries.

Li plays Huo Yuanjia, a real Chinese martial arts hero who defeated foreign fighters in highly publicized bouts. Early in the film Li's haughty warrior Huo takes a sip of what looks like tea and grimaces. "This tastes horrible! What's is it?" His companion answers, "It's coffee. It's a western thing," and goes on to lament, "these are troubling times. The west is dominating us." Li's Huo is a high-handed, violent drunk and must rediscover humility through tragedy before he can fight honorably for national pride. As usual, Ronny Yu's film is beautifully shot and Li's fight scenes are impeccable.

12. Come Drink With Me (1966)

"Come Drink With Me" from 1966 holds up much better than the cartoonish kung fu movies coming out of Hong Kong in the 1970s that made the genre a global phenomenon. This taut 90-minute martial arts treat is bloodier, more bathed in moody shadows, and more full of convincing swordplay than later candy-colored Shaw Studios confections like "The Five Deadly Venoms." The plot is mercifully simple: When the son of a governor is abducted by a murderous gang of bandits, a legendary swordswoman named Golden Swallow decides to rescue him. Along the way, she meets a local drunk who turns out to be a martial arts master too, and Kung fu fisticuffs ensue. Swallow was played by gifted and poised 19-year-old Cheng Pei-pei, who would be the model of all later deadly and graceful female kung fu stars.

The fight scene setups in "Come Drink With Me" owe more to swaggering American westerns than the feudal-inspired melodramas that followed. The film shows signs of its age for sure, as numerous key close-ups are just plain out of focus. Chinese filmmakers were still figuring out those tricky anamorphic lenses in 1966, but it's otherwise more recognizably cinematic than the flat, Brady Bunch-level cinematography of Shaw Studios films in the decade that followed. The most important aspect is that Pei-pei can seriously crack, and her first major work is immensely compelling all these decades later.

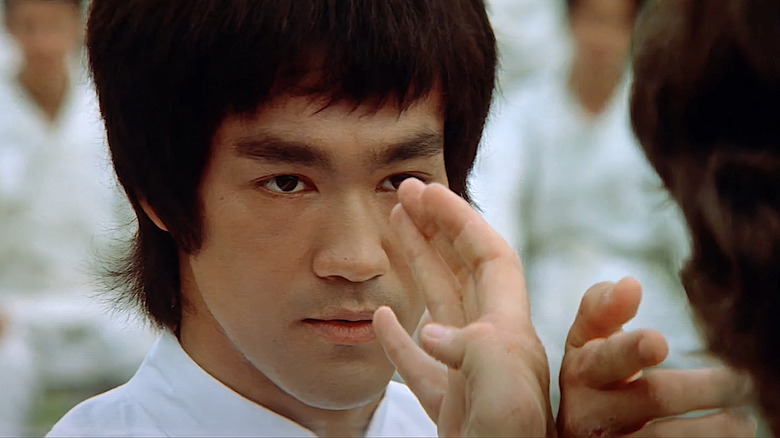

11. Enter The Dragon (1973)

"Enter the Dragon" is sort of obligatory on lists like these and can reasonably be dinged for its slipshod craft and mediocre fight choreography. However, there's still no martial artist who oozed more intensity than Bruce Lee at the height of his powers, though he would die suddenly just before the film's release from an allergic reaction to medication. The suspicious-sounding tragedy has certainly added to the film's enduring power.

"Enter The Dragon" still works in part because of its simplicity, with no CG bullet-time cliches that age like cheese, yet this kung fu classic should be understood for what it was: The first joint production between Hong Kong and U.S. studios, and a naked attempt to horn in on the martial arts market. The plot is ridiculous, and the action (aside from that excellent mirror scene) is not as inventive as many Wuxia pictures that preceded it. "Enter The Dragon" endures simply because of the presence and legend of Lee.

10. Supercop (1992)

Kung fu movie fanatic Quentin Tarantino believes Jackie Chan's "Police Story 3" (better known in the US as "Supercop") contains, "probably the greatest stunts ever filmed in any movie ever." As usual, Chan paid the price when the action star was hit with a fast-moving helicopter in the film's dramatic train-top finale, leaving him dangling from a pole with his shoulder muscles torn. The accident can be seen in the usual end-credits montage of mishaps, which are generally the best and most endearing part of Chan's impressive films.

"Supercop" is both an ironic and literal title in this capper to Chan's "Police Story" trilogy. When he's hired for a deadly undercover mission and billed to his new superiors as a "supercop," he raises his eyebrows in comic dismay: "Supercops in Hong Kong are cheap and plentiful," he says with a nervous smile. This isn't false modesty. His characters are lovably mortal, even if Chan himself seems to have nine lives. The 1995 flick "Rumble in the Bronx" could easily take this spot too, expanding on the comedic style of Chan-fu. Chan's great innovation was to make it clear his characters value their lives, want to avoid violence, and definitely experience pain during fights. It seems like a no-brainer change to the kung fu canon, but all great ideas seem obvious in retrospect.

9. John Wick, Chapters 1-3 (2014-2019)

There's no real consensus on the best "John Wick" installment. The original is a modern action classic, and the initial sequel has the highest aggregate critic's and audience score (if you put stock into such things), but "John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum" is the best pure kung fu movie of the bunch. The franchise is best seen as a contiguous work.

Halle Berry shows up as a fellow assassin, and despite only training six months, proves a capable foil. Director Chad Stahelski deserves praise for not resting on his laurels in this third film that ups the stakes and tops the previous fight scenes in both style and inventiveness. The gruesome action is buoyed with black humor in a franchise that never takes itself too seriously. So many modern kung fu movies use long lenses and quick editing to hide weak choreography, but Stahelski consistently pulls back to wide angles and lets the slightly rickety Reeves (at age 55) do the heavy lifting in extended fight sequences that conceal absolutely nothing.

8. Ip Man (2008)

"Ip Man" is like the Mr. Miyagi prequel we should've gotten decades ago, but didn't. It's one of the better kung fu elevator pitches ever: What if the story was about the master instead of his annoying apprentice? "Ip Man" is tenuously based on Bruce Lee's real mentor, a Wing Chun practitioner from Foshan, China, but that's where the true story ends. In the movie, the Japanese invade Foshan in the early stages of World War 2, and Ip must defend his community from a villainous foreign general who wants his kung fu secrets. Lead Donne Yen wanted the secrets too, eventually studying Wing Chun with Ip Man's actual kids. He's also an accomplished and surprisingly ripped martial artist in his own right, which is why his battles with various Japanese baddies and local toughs are the best-choreographed fights in the kung fu canon.

"Ip Man" is one big excuse for fistfights and is far less romantic than classic Wuxi pictures (Ip's wife is left mostly unattended, and though she briefly objects, quickly gets over it.) As a hero, he's a combination of Jesus, Buddha, and a young Clint Eastwood: self-sacrificial, wise, unflappable, and utterly unbeatable in a showdown. His near god-like prowess should ruin the tension, but this isn't an underdog story. "Ip Man" is the ultimate martial arts alpha fantasy and Yen's "northern style" reigns entertainingly supreme.

7. Hero (2002)

"Hero" has some of the best kung fu action ever committed to celluloid. It's also a totalitarian propaganda film dressed in spiritual garb and fancy photography. It expertly cribs the romantic beauty of "Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon" as it makes a straight-faced case for a historical tyrant pursuing bloody wars of aggression. Jet Li plays "Nameless," a swordsman orphaned by King Qin's murderous ambitions. He plots his revenge, but in the end it's he and his fellow working warriors who fall on their swords as Qin goes on to glory and central dominion over China.

"Hero" is a fascinating time-capsule of the moment China began making spectacular-looking commercial films asserting an inverted version of American cinema, where rugged individuals usually overcome the system. Conversely, "Hero" is all about tragic sacrifice for oppressive collectivism as Qin's vast Greek chorus of identical armed guards demand greater acts of despotism. The human toll here is painted as both poetic and glorious. Is Li's Nameless a stand-in for Taiwan? Uyghur Muslims? Tibet? "Hero" is an important and compelling film precisely because it is so troubling. Not since Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will" has such expert filmmaking been used to glamorize unchecked tyranny. As China ascends to being a global superpower, "Hero" might be the best-made, most unsettling, most consequential kung fu film ever made.

6. House of Flying Daggers (2004)

The dead giveaway you're watching a low-budget movie is the whole thing takes place in the woods. "House of Flying Daggers" uses this money-saving technique so much that the film's titular warriors definitely don't even have a house (more like a modest shack in the background), and yet the film is stunning. It makes the most of its modest $12 million financing by shooting in a gorgeous Chinese national park as leaves turn to spectacular colors in autumn. The rest of the budget is definitely invested in CG flying daggers that probably don't look as cool as they did in 2004, but still work in the suspended-belief context of Wuxia filmmaking.

"House of Flying Daggers" is "Romeo & Juliet" if the Capulets and Montagues were dagger-wielding kung fu clans. Zhang Ziyi plays a wayward member of said dagger house, and Takeshi Kaneshiro plays a handsome government cad leading her through the forest to discover the location of her rebel tribe. They're both running a con in this operatic melodrama, but as their romance blooms, it's clear that larger forces (and their own priors) will endeavor to keep them apart. It's all very beautiful, action-packed, and almost totally without the thematic depth of a film like "Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon." This is a tremendous popcorn movie worth watching for the famous bamboo-forest fight scene alone, but the story keeps you hooked until the film's snow-coved finale fails to cool the hot-blooded passions of these star-crossed lovers.

5. Rush Hour 1 & 2 (1998-2001)

"'Rush Hour' isn't a kung fu movie!" shrieks the straw man purist I'm inventing for this article, but this person totally exits. Look at almost any listicle of the best kung fu movies and note that Jackie Chan's indisputable 1998 pop-masterpiece (and excellent 2001 sequel) are conspicuously absent. That's a serious shame. If "Rush Hour" isn't a kung fu movie then the iPhone isn't a phone just because it's awesome in other ways too. Chris Tucker's street-wise Los Angeles cop James Carter certainly understands he's in a kung fu movie. He takes every opportunity to mock the eastern flair of Jackie Chan's Lee, a Chinese cop who has come to L.A. to help investigate the abduction of a diplomat.

Chan's subtle upstaging of Tucker's brash American is one of the best kung fu crossovers of all time. The graceful way Lee gets into Carter's ostentatious convertible alone is his elegantly dignified comeback despite this buddy-cop duo's language barrier. Chan helped with the choreography of key fights scenes and (as always) put his body on the line, suffering a leg injury in the sequel as he tried to scramble up some wet bamboo. Chan's freak athleticism and bravery are summed up in the testimony of a stuntman who got pulled under a moving boat during "Rush Hour 2" and nearly drowned. "I feel like a god grabbed me and pulled me out of the water," the grateful performer told Reuters (via ABC News).

4. Shadow (2018)

"Shadow" is like "300" meets "Old Boy" meets "Hamlet." It replaces the cartoonish colors of 1970s Wuxia classics with an austere grey palette that verges on black and white. Saturation is saved for skin tones, and the great pools of blood unleashed in this stylish feudal fantasy from the master of modern Wuxia filmmaking, Zhang Yimou. "Shadow" mostly takes place in the royal court of a youthful but decadent king. His top general is the eponymous "shadow," a gifted body double for a dying man long hiding at court and plotting to take power for himself. This shadow is a mere commoner caught up in kingly power games and must play all sides to survive as he falls for the wife of his scheming master.

Zhang's film may lack saturation, but it's a study in contrasts and duality: masculine and feminine; the good king and the bad king; the scheming general and his shadow. Images of the yin and yang are constantly evoked. It's all interesting stuff if you can get through a slightly ponderous first act full of palace intrigue to the final showdown fought with razor-sharp umbrellas. "Shadow" has the best set design of any Wuxia film, but strangely hides much of it for the last act of this ultra-violent film. In the end, Zhang's most artful effort really repays your attentiveness with a heaping pound of flesh.

3. The Matrix (1999)

"The Matrix" is one of those films that is so copied and parodied it's all but impossible to look at it with fresh eyes and realize what a revolution it was in 1999. Will Smith's hilarious summary of why he turned down the lead as Neo sums it up. Basically, he thought The Wachowski's pitch was insane because it relied on them inventing a bunch of as yet non-existing technology to create kung fu action the world had never seen.

It's not like Keanu Reeves doesn't get enough good press, but neither he nor Laurence Fishburne was a serious martial artists before the film. Reeves said he trained four months leading up to the shoot and neither man's performance lacks for anything. All that slow-motion bullet-time stuff is so ubiquitous it's become a cringy cliche. This film completely changed the audience's expectations for kung fu movies, as evidenced by films like "Hero" chock-full of that super slow-mo aesthetic. We're all still waiting for the next film that revolutionizes the genre and has everyone scrambling to imitate.

2. Kill Bill Vol. 1& 2 (2003-2004)

Quentin Tarantino's "Kill Bill" duology is arguably the best kung fu film ever made, but not exactly because it's the peak of martial arts ... though the dedicated cast trained eight hours a day for months. "I thought I was in the damn Olympics or something," Vivica A. Fox recalled. Endless credit also goes to swordfight choreographer Tetsuro Shimaguchi, but really Uma Thurman and company didn't become Michelle Yeoh in a single training camp, and it doesn't matter one bit. The power of Tarantino-fu flows from the director's mastery of mood and pacing. He crafts every scene by building anticipation and then delivering a payoff. The sword battle between Thurman's Bride and Lucy Liu's O-ren Ishii is the most sublime fight because Tarantino brings the same attention to the rhythms of a battle as he does to a conversation about cheeseburgers in Paris in "Pulp Fiction."

So many modern directors lean on multi-cam shooting. They may carefully block out a scene, but then throw up tons of "coverage" and end up making their movie in post anyway. Tarantino-favorite Tony Scott used this style. Plenty of good directors can make it work, but the best filmmakers know exactly what they want, and that only takes one camera and one master's stroke. "Kill Bill" is the fetishistic auteur's most faithful recreation of a vintage genre and one that both honors, even enriches the kung fu and samurai films that inspired it.

1. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)

The title of "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" is a metaphor for the feelings this story's powerful Wuxua warriors keep bottled. Ang Lee's 2000 masterpiece is exactly the kind of restrained, elegant foreign film Academy members like, and it picked up four Oscars among a slew of well-deserved nods in 2001. It's the culmination of generations of filmmaking about sword-wielding heroes with supernatural martial arts prowess on romantic adventures in feudal China.

When hero swordsman Li Mu Bai (Chow Yun-fat) finds his teacher is murdered by rogue assassin Jade Fox (Cheng Pei-pei), he has a spiritual awakening. He rejects a Wuxia revenge plot and instead pledges his love to a fellow warrior, but when he gives his legendary Green Destiny sword to a local magistrate, this official's young daughter Jen Yu (Zhang Ziyi) steals it. She's a dutiful aristocrat by day but a haughty and conceded kung fu savant under the tutelage of Fox by night. Jen wants freedom from the burdens of her place but soon finds the romantic warrior life is not exactly the liberation of her fantasies. She must face Bai, Fox, and the shattering consequences of her own arrogance. "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon" is about the tension between duty and desire in the honor society of 17th century China, but it's also a somber tragedy with a beautifully ambiguous finale that denies us simple answers. Just like in the ecstatic ballet of this film's stunning swordplay, there is only choice and deadly consequence.