Seven Samurai Ending Explained: From Japanese History To The Gig Economy

Akira Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai" invented a premise, and in so doing, invented a genre. From "Seven Samurai," you can trace a direct line to "The Magnificent Seven," John Sturges' 1960 remake set in the Old West. From there, you can connect the dots with samurai films remade as Spaghetti Westerns in Italy. But really, all "man on a mission" stories are children of "Seven Samurai," and the expanded action climax of Kurosawa's 207-minute film would come to inform the way modern audiences think about onscreen action. As such, "Seven Samurai" remains one of the most influential films of all time.

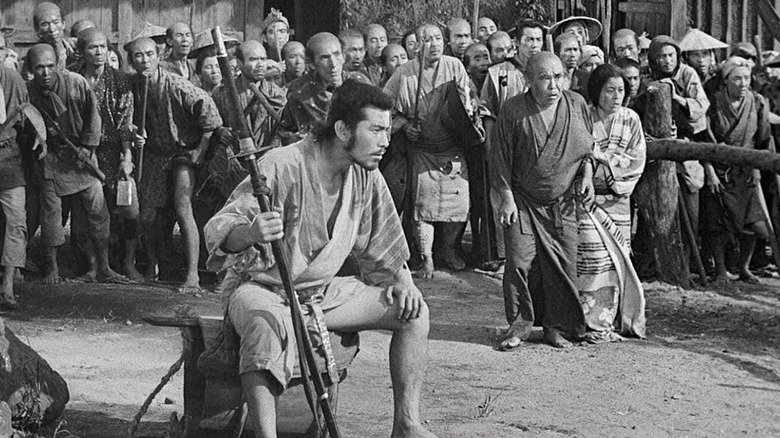

The premise seems rudimentary now: A remote, impoverished village is beset by bandits, and cannot survive another attack. Before the bandits are set to return on one of their annual raids, the villagers gather what meager payment they can offer — essentially just room and board — and go to a nearby city to hire an army of freelance samurai to protect them. The villagers, however, cannot afford the more popular samurai, and end up with a motley gang of seven men that includes Kurosawa regulars Takashi Shimura, Daisuke Kato, and Toshiro Mifune, all of whom decide to protect the village for their own reasons. If that story seems familiar, it's because "Seven Samurai" has been used as a template for everything from animated films ("A Bug's Life") to low-budget sci-fi ("Battle Beyond the Stars") and "Star Trek" spoofs ("Galaxy Quest").

Indeed, the concept behind "Seven Samurai" is so strong, you might assume it was based on ancient history or a Japanese folk tale. It was, in fact, Kurosawa's invention, as well as that of the film's two other screenwriters, frequent Kurosawa collaborators Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. The original idea was "Six Samurai," but the screenwriters felt that the idea of six straight-laced samurai wasn't terribly interesting. So they added a "wild card" character in the form of Kikuchiyo (Mifune), who was encouraged to improvise a lot of his material as a counter to the mannered steadfastness of his six colleagues.

The elevator pitch

The plot itself is straightforward: The villagers offer the samurai a handful of rice a day and a bed to sleep in as payment. The seven samurai agree. They have a little trouble interacting with the villagers, but spend the bulk of the film shoring up the village's defenses and training the villagers what to expect when bandits come calling. There's a terrific series of action sequences, and, by the end, the samurai will be successful ... but not without casualties. This is an elevator pitch par excellence.

Indeed, the story is so clear and efficient, the ending of "Seven Samurai" doesn't warrant too much of an explanation. Even if some of the smaller nuances of the plot are lost to a flagging attention span (although how one could not be riveted during "Seven Samurai" is beyond me), the sight of several burial mounds give a visual cap to the epic viewers have just witnessed.

The central mystery of "Seven Samurai" is instead why the septet would agree to such a difficult, long-lasting, and potentially fatal task as defending this small village. The villagers themselves make little argument as to why they should be helped; indeed, they rarely emerge as individuals, often moving in a mass and speaking together in the same note. Poverty has destroyed their individuality. So the samurai are not doing anyone a personal favor.

As it turns out, the reason the samurai agree to help reflects some of the deeper aspects of Japanese culture.

Historical realism

In his book "To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema," film writer Noel Burch offers his sociological perspective on Japanese culture to "explain" some of the underlying themes in "Seven Samurai" to an American audience. Although the characters are fictional, they tap into a cultural sense of social obligation. As in most cultures, the seven samurai have a powerful need to fulfill a sense of purpose, and their devotion to protecting the village speaks to a larger cultural contract. The samurai have to do the best they can, because that is their role. Even the villagers — and, by extension, the bandits — have their roles to fill, and will play them as best they can.

Samurai emerged in 12th century Japan, where they served as specialized military protectors of the royal courts. Samurai were regularly employed by the Japanese aristocracy until their abolition in 1876. There is no simple way to sum up centuries of samurai history, as over the centuries, they served many functions: They have been a warrior class, a freelance military, courtiers, and professional entrepreneurs.

"Seven Samurai" takes place in 1587, known as the Sengoku period, which was a time of great expansion of the samurai class. Thanks to improvements in weapons and armoring technology, more people had access to the equipment needed to become a samurai. And so many people, regardless of class, could break into the trade. (Kikuchiyo is a prime example of this: There's some ambivalence when we first meet him that he may just be someone with a lance and some armor who has never actually worked as a samurai before.) But this also meant that samurai were victims of the gig economy, often falling into destitution unless they could find a job. Being a samurai was considered prestigious, but there wasn't always enough work to go around.

The difference between samurai and bandits

Kurosawa was a big admirer of filmmaker Kenji Mizoguchi, whose period films were noted for their historical accuracy. And for his first samurai film, Kurosawa sought to outdo Mizoguchi by using only period-accurate materials to make clothes and props.

He also set his film in the late 16th century for a reason: Since samurai culture was relatively splintered, and requirements were looser than they had been before, the setting allowed modern audiences to draw a parallel between the samurai and the bandits. Both the samurai and the bandits are as destitute as the villagers, and these groups are fighting over a modest patch of land and the food it might produce. The difference is that the samurai are moral characters who understand the profound humanity of defending another human being, while the bandits only care about self-gratification and destruction.

As such, "Seven Samurai" is a morality play. During times of destitution, we all have the potential to be a bandit, and the potential to be a samurai. There is no divine right that entitles us to aristocracy, nor is there any situation so awful that we must become a bandit. "Seven Samurai" is about how the correct thing to do can be an easy choice, even if it requires hard work and sacrifice.

Kurosawa was a deeply humanist director, and his films tend to center on the moral choices that make us human. His films tell corking stories that feature amazing action and filmmaking, but it's the eternal battle between hope and despair that drives his filmography forward. And that's the real takeaway from "Seven Samurai" — the fact that people did the right thing.