Year Of The Vampire: Matt Reeves Invites Darkness Across The Threshold With Let Me In

(Welcome to Year of the Vampire, a series examining the greatest, strangest, and sometimes overlooked vampire movies of all time in honor of "Nosferatu," which turns 100 this year.)

"Let Me In" is a movie cut from the same cloth as David Fincher's "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," insofar as it's an American remake or re-adaptation of a Swedish novel that had already received a Swedish film adaptation just two years earlier. Like Fincher's film, "Let Me In" has some teeth to it. In this case, they're vampire fangs. However improbably, this superficial retread somehow manages to justify its existence as the tale of a lonely individual, preyed upon by others, who comes into their own as they forge a connection with someone in a snowy setting.

That first adaptation of John Ajvide Lindqvist's book, which bears the same title, "Let the Right One In," is a film that we've spotlighted twice in recent months: first, in our Daily Stream series, then again here in our Year of the Vampire series. What makes this version, "Let Me In," worth revisiting now is its timely link to several water cooler names and its thematic relevance to ongoing world events. It also just happens to be a good movie.

Released in 2010, "Let Me In" marks an early collaboration between director Matt Reeves and composer Michael Giacchino, the dynamic duo behind "The Batman," in theaters this week. The film's protagonist, Owen, is also played by a young Kodi Smit-McPhee, who is up for an Oscar this month for his work in Jane Campion's "The Power of the Dog." That movie takes its title from a line of scripture: "Deliver my soul from the sword; my darling from the power of the dog." In "Let Me In," Owen's barefoot darling is a vampire named Abby (Chloë Grace Moretz), who will deliver him from the power of school bullies against an Americanized backdrop of Reagan-era politics and religious othering.

What it brought to the genre

"Let Me In" brought a different kind of indie-sleeper romance to the vampire movie genre at a time when "The Twilight Saga" was midway through its run of blockbuster YA success. Reeves' film, by contrast, opened at #8 at the box office and barely recouped its $20 million budget, perhaps because it came so soon after "Let the Right One In" and because Hollywood was beginning to reach a saturation point in terms of the renewed vampire craze.

As a genre entry, "Let Me In" also remains noteworthy in that it helped bring Hammer Films back from the dead. Beginning in the mid-to-late 1950s, the Hammer Horror brand had become associated with sexy bloodsuckers through "Horror of Dracula" and its eight sequels (seven of which starred Christopher Lee) along with other titles like "The Vampire Lovers" (and the rest of the Karnstein Trilogy), which drew from the 1872 pre-"Dracula" lesbian vampire novella, "Carmilla," by Sheridan Le Fanu.

With such a rich tradition of vampire movies, it was only appropriate that Hammer should resurrect itself in true undead fashion with "Let Me In." The movie even opens with a Marvel-style Hammer logo, where old movie poster art flashes through the letters.

Giacchino's music leads the way as the film sets us down in Los Alamos, New Mexico, in 1983. It's a time when the Satanic panic is in full swing, as evidenced by the first line of police questioning. "Are you a Satanist?" a detective asks a disfigured hospital patient. "Are you involved in some kind of cult?"

At home, Owen's mother prays before eating, but she's a blur in the background or a head above frame. In "Let Me In," religiosity lurks on the perimeter as a way of reinforcing the film's themes. Giacchino's score adds a sweet texture, yet this is a movie about projecting evil onto others, while reckoning — or refusing to reckon — with it in ourselves.

"If America ever ceases to be good..."

In a conventional Hollywood script, outlined with a beat sheet, there would come a moment early on where there is a statement of theme for the movie. It's that moment in "Halloween," for example, where Laurie Strode's teacher is talking about fate's inevitability and Laurie looks outside to see the masked killer, Michael Myers, standing across the street.

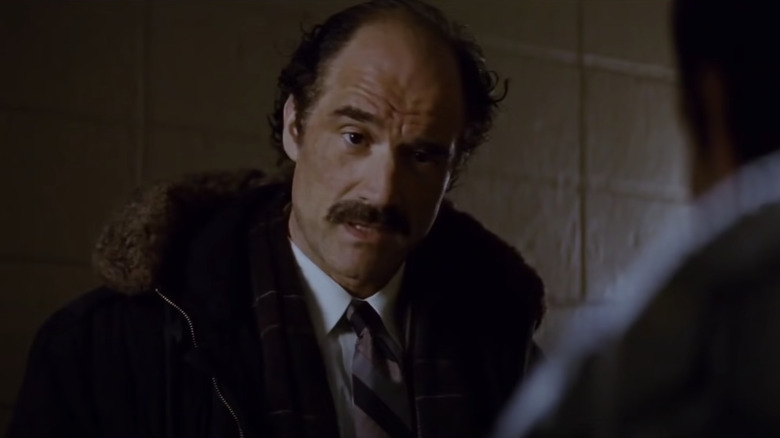

In "Let Me In," we get a beat like that around the 7-minute mark. It comes when the unnamed detective, credited as "The Policeman" (Elias Koteas), steps outside the hospital, where he sees the disfigured patient, a victim of self-inflicted acid burns, lying dead on the ground after falling from his window.

For about 45 seconds, the camera lingers in a stationary spot inside the hospital, looking through the glass door at The Policeman as President Ronald Reagan's "Evil Empire" speech plays on the television inside and a nurse's dark reflection eventually approaches. We're literally seeing through a glass, darkly, per the biblical phrase.

Reagan's speech, which has a theocratic ring to it, was given to the National Association of Evangelicals at the height of the Cold War. In it, Reagan sought to frame the conflict between the U.S. and Soviet Union as a spiritual battle between the forces of good and evil. The part that we hear in the movie is as follows:

"There is sin and evil in the world, and we're enjoined by scripture and the Lord Jesus to oppose it with all our might. Our nation, too, has a legacy of evil with which it must deal. The glory of this land has been its capacity for transcending the moral evils of our past. Alexis de Tocqueville put it eloquently after he had gone on a search for the secret of America's greatness and genius, and he said, 'Not until I went into the churches of America and heard her pulpits aflame with righteousness, did I understand the greatness and the genius of America.' America is good. And if America ever ceases to be good ..."

Reeves leaves that "if" hanging open-ended.

Russia's recent invasion of the Ukraine has once again made it the enemy in the news, but in "Let Me In," the director seems to be invoking the Cold War and the Satanic panic as a means of making a larger point about human nature.

Battle not ye with monsters

As humans, we look for scapegoats outside ourselves, monsters, Others, to whom we can assign blame. The great moral contradiction of the Satanic panic is that, while church members were focused on phantom cults conducting ritual abuse, the real epidemic of child abuse — warned about in a 1985 report by Father Thomas P. Doyle — was going on at the hands of trusted clergymen.

American heroes fought villains with foreign accents in action movies derivative of "Die Hard" (a Reagan-era film), while some of the country's own internal problems were left to fester for decades. At one point, "Let Me In" shows an actual dumpster fire, a visual manifestation of the phrase often used to describe the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Owen's mother insists that he's a "good boy," but after Abby goes feral and vampiric at the sight of his blood, he's left asking, "Do you think there's such a thing as evil? Can people be evil?"

The lead bully of "Let Me In," Kenny (played by "13 Reasons Why" star Dylan Minnette), does initially come across as evil in the way that he harasses Owen: giving him painful locker-room wedgies and lashing him across the face with a car antenna. Yet Owen himself has issues. His room is where "Taxi Driver" meets "Rear Window" in a creepy, pint-sized fashion. At school, he pledges allegiance to the flag, but at home, we see him in a mask like something out of a home invasion movie, menacing his own mirror with a kitchen knife, saying, "Hey, little girl. Are you a little girl? Huh? Are you scared?"

Then, he proceeds to spy on his neighbors with his telescope. "Little girl" is what Kenny calls Owen when he's bullying him. The implication is that Owen, while powerless to do so on his own, fantasizes about turning the tables on his attackers and perhaps even becoming a bully himself. It brings to mind that famous Nietzsche quote: "Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you."

Right after Abby agrees to go steady with him, Owen is empowered to stand up for himself on a school ice-skating trip. She has told him, "You have to hit back hard. Hit them harder than you dare, and then they'll stop." So that's what he does.

Gaze into the outer darkness

With a metal pole, Owen does a Peter-in-Gethsemane number on Kenny's ear. At the same time, the screams of other students ring out across the lake. They've found the frozen remains of the victim Abby drained in a horrific tunnel attack, while posing as a child in need of help. Her adult companion, Thomas (Richard Jenkins), tried to dispose of the man's body, but now it has reappeared, as if to give a glimpse of the future murders that Abby's new companion, Owen, will commit.

In the long run, Abby's advice to Owen only escalates the situation with Lenny. As it turns out, Lenny is also human: he gets bullied and called a little girl by his sadistic older brother, who comes back for revenge and tries to drown Owen. Abby is there to save him and kill all the bullies, and on the one hand, it's narratively satisfying to see them get their comeuppance. On the other hand, Abby follows the "Interview with the Vampire" playbook, whereby "evil is a point of view" and bloodsuckers are free to kill indiscriminately.

She's already slaughtered The Policeman, devoured one neighbor, and left another half-eaten and doomed to a fiery death by sunlight. We know that Owen will kill for her, maybe hanging people upside-down from a tree, like Thomas did, and draining their blood into jugs she can drink. He's come a long way from the petty crime of stealing money out of his mother's pocketbook, while being confronted with the sight of a Jesus portrait on her mirror. Owen has battled with monsters, and now he's ready to become one.

The year before "Let Me In," McPhee co-starred with Viggo Mortensen in "The Road," based on Cormac McCarthy's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. McCarthy also wrote a book called "Outer Dark," which, like "The Power of the Dog," took its title from scripture — a Gospel line describing the "outer darkness" as a place where "there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth."

In "Let Me In," the darkness, personified by Abby, is outside Owen, waiting to be let in. He embraces his dark side and receives a bloody vampire kiss from it, but it could someday leave him burned and unrecognizable like Thomas. It's a bittersweet ending to a movie that remains a worthy and meaningful addition to the vampire canon.