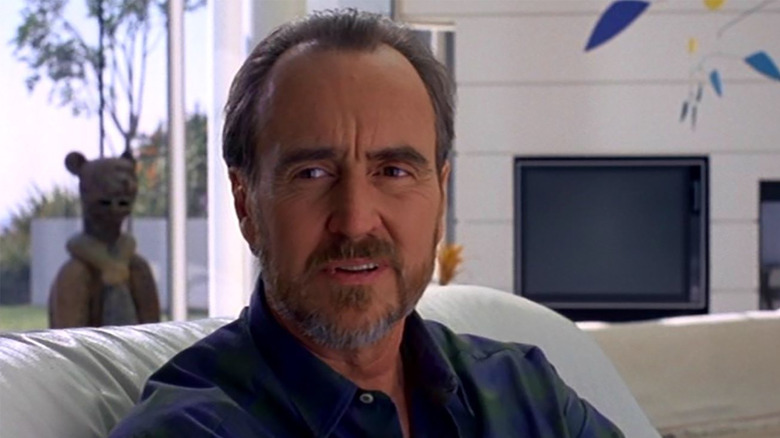

These Are Wes Craven's Favorite Horror Movies Of All Time

Wes Craven is the man behind some of the greatest and scariest horror movies ever made, so any film that could scare him must be pretty terrifying stuff. He was a bit of a soft touch for movies in general, however, having been denied the pleasure of moviegoing as a child due to an overly strict religious family. Craven's family "didn't think movies were a good thing—they thought they were the work of the devil," and as such Craven's cinematic education didn't begin until he had graduated college. Thanks to having access to "an art house in the town way upstate in New York" where he worked as a teacher, Craven got a crash course in the horror genre, becoming exposed to films that had a particular focus on the more thoughtful and thematic aspects of horror. It was these movies that influenced him the most, having an effect on both his work in the genre and his nightmares, which Craven often claimed fueled his movies. So let's dig into Wes Craven's favorite horror movies of all time!

Don't Look Now (1973)

"Don't Look Now" is not the first (or last) horror movie about the ravages of grief, but it is easily one of the most hauntingly powerful. The film follows John Baxter (Donald Sutherland) and his wife Laura (Julie Christie) as they travel to Venice, Italy some time after their daughter has tragically drowned. While there, the Baxters encounter a series of characters who claim to be able to contact the couple's daughter in the beyond, and soon enough John begins seeing glimpses of a girl who seems to resemble her. The nightmarish dream logic of the film appealed to Craven, who remarked that director Nicolas Roeg's style demonstrated "a wonderful example... of being able to scare without showing blood." While Craven admittedly didn't quite follow that example, his mastery of the surreal was undoubtedly influenced by Roeg's film.

Blow-Up (1966)

The first of a couple films on Craven's list that aren't necessarily considered horror, Michelangelo Antonioni's "Blow-Up" is a paranoia thriller saturated in the mod culture of '60s London. In it, the swinging fashion photographer Thomas (David Hemmings) gallivants around sleeping with various women and getting his kicks in other ways, such as surreptitiously taking photos of a couple in the park. Thomas develops the film of those pictures, revealing that a third person was near the couple in the park with a gun. Thomas becomes obsessed with revealing the truth behind that encounter, putting himself in danger as a result.

Craven found the film "masterfully constructed," with Antonioni providing a sense of "impending threat and doom" that was "almost surreal," a quality that Craven felt allowed him to explore "macabre visions" in 1984's "A Nightmare on Elm Street." In addition to that landmark work, Craven also used some of "Blow-Up" in 1988's "The Serpent and the Rainbow," telling a story about a man trapped in increasingly surreal and menacing events as he investigates a mystery.

Psycho (1960)

Craven was not immune to the charms of Alfred Hitchcock's "Psycho," one of the most influential horror films ever made. A watershed movie that led to the establishment of the slasher subgenre, "Psycho" follows — at first — secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), who steals thousands from her boss and blows town, stopping at an eerie roadside motel run by Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins). After Marion goes missing, a detective (Martin Balsam) investigates the motel, running into the murderous "Mrs. Bates."

Craven found this scene the one that scared him the most, impressed at how "Hitchcock did a very surreal thing" in filming the detective's death with a stunt he'd used at least once before. Finding the sequence "dreamlike," Craven not only took inspiration from Hitchcock for the exploits of Freddy Krueger, but for the Ghostface(s) of the "Scream" series.

The Virgin Spring (1960)

Ingmar Bergman isn't generally thought of as a horror filmmaker, but he wasn't afraid to dive into the darker side of human nature, and "The Virgin Spring" does just that. Adapted from a 13th-century Swedish tale, the film concerns a man (Max von Sydow) who asks his daughter (Birgitta Pettersson) to bring candles to a nearby church. Along the way, the daughter and her servant encounter some men who make unwelcome sexual advances toward them, with the daughter ending up raped and murdered. The father then unknowingly takes in his daughter's murderers when they seek shelter, and upon learning of their deed decides to take justice into his own hands.

Craven effectively remade the film into his debut feature, 1972's "The Last House on the Left," which sets the tale in modern day and is much more explicit than Bergman's movie. He was especially disturbed by "The Virgin Spring" in its depiction of the father deciding to kill his daughter's assailants, the resulting murders being "the most terrifying because his revenge was done so graphically." Craven became fascinated by the notion that "revenge can itself be a murder of the innocence of the victims, how they can transcend from being normal people to being victims to being murderers themselves," a theme that appeared in his films throughout his entire career, up to and including his final movie, "Scream 4."

Repulsion (1965)

A few years before he made a splash in America with "Rosemary's Baby," director Roman Polanski made this similarly eerie and paranoid thriller about a young woman (Catherine Deneuve) who loses her grip on reality as her own sexual neuroses (coupled with constant advances from the men in her life) cause her to react violently. Making the movie from the woman's perspective gives Polanski license to use a lot of surreal, dreamlike imagery, resulting in scenes that influenced Craven so heavily they cropped up in his work on an unconscious level.

In "Wes Craven's New Nightmare," the director's 1994 return to the Freddy Krueger mythos, Craven stages a scene where an earthquake causes a giant crack to appear in the home of Heather Langenkamp, indicating Freddy's emergence into the real world. The scene references a similar moment in "Repulsion," but Craven didn't realize it until he introduced a screening of Polanski's film years later. It's fitting that a film employing strong subconscious imagery would become an unconscious image itself for a director continually obsessed with the dream world.

Beauty and the Beast (1946)

Jean Cocteau's adaptation of the classic Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont fairy tale tells essentially the same story as the numerous other versions of "Beauty and the Beast" made over the decades. A young maiden named Belle (Josette Day) is imprisoned and then enraptured by the Beast (Jean Marais), a victim of a magical curse. The lasting power of Cocteau's film lies in its hauntingly surreal imagery, presenting the Beast's castle as a place of ominous magic.

Once again, Craven was taken with the film's surrealism, seeing the technique as "a sort of outlaw form of looking at the world as semi-mad." The image that troubled him the most is of the castle's hallway lights having hands for sconces, hands that would occasionally reach out at people as they walked by. Craven sought to recreate that image in several of his films, with moments from "The People Under the Stairs" and "The Serpent and the Rainbow" recalling "Beauty and the Beast's" reaching hallway hands (an image that also, perhaps not coincidentally, was used in Polanski's "Repulsion").

War of the Worlds (1953)

Byron Haskin's film version of the classic H.G. Wells sci-fi novel, in which martians attack the Earth, is a sterling example of 1950s alien invasion horror with the terror stemming from the eerie unknowable threat of the invading forces. One of the few movies Wes Craven was able to see as a kid, the future horror director was "totally terrified" by art director Albert Nozaki's designs for the Martian war machines, which Craven described as having "goose-neck lamp material" that are "very serpentine with a kind of snakelike head" as they hunt for their human prey. Craven wasn't the only filmmaker haunted by the menace of these saucers — Steven Spielberg made sure to include an updated version in his 2005 remake.

Frankenstein (1931)

James Whale's film version of Mary Shelley's immortal tale was primarily based on a stage play adaptation by Peggy Webling and John L. Balderston, one which revamped the man-made Monster (Boris Karloff) into a mute creature seeking acceptance from the humans surrounding him, especially his creator, Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive). Whale's film became a foundational part of Universal Studios' horror cycle, causing a sensation in part because of how transgressive it was. Craven certainly thought so, shocked especially by the scene where the Monster attempts to befriend a little girl (Marilyn Harris) before accidentally killing her.

Craven was moved by "that sense that a movie can show you something you just don't think a movie is going to show you," and while only a couple of his films put little children in danger, the bulk of his work involves young people in peril or worse, the director making a similar transgression to Whale's.

Nosferatu (1922)

F.W. Murnau's unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker's "Dracula" created one of the most iconic and indelible horror images: the hairless, toothy, rat-like visage of the vampire Count Orlok (Max Schreck). The film is built around that masterstroke of character design, with Murnau milking Orlok's every possible angle, including and especially his silhouette. Craven so loved the design for its uncanny qualities, looking to him "like it couldn't actually be a human actor in there." His love of that look of Orlok influenced his casting of actor Michael Berryman as the cannibal Pluto in 1977's "The Hills Have Eyes," the performer's numerous birth defects lending him "an extraordinary look."

The Bad Seed (1956)

Mervyn LeRoy's adaptation of Maxwell Anderson's play centers on the precocious eight-year-old Rhoda (Patty McCormack) who begins to exhibit signs of sociopathy, eventually surreptitiously murdering a series of victims to her parents' horror. Coming into a cinematic landscape where child characters were generally seen as sacrosanct in addition to automatically innocent, Craven was delighted by the character, believing her to be "so revolutionary and so anti-American, where the nice little girl could never be bad."

Despite being taken with the film, Craven never made a movie that directly homaged or remade it, but themes of hereditary sociopathy are all over his work, from "Shocker" to "My Soul to Take." There are also murderous female characters throughout his films, starting in "The Last House on the Left" and continuing through "Deadly Friend" and several "Scream" installments.