The Classic Anime That Inspired The Matrix

It's hardly a secret that 1999's sci fi martial arts blockbuster masterpiece "The Matrix” was inspired by 1995's generation-defining cyberpunk film "Ghost in the Shell." "The Matrix" is packed with references to its predecessor: head jacks in the back of the neck, exploding watermelons, a woman in tight clothing falling from a great height through the city. Even the green color grading in "The Matrix" looks to be influenced by "Ghost in the Shell."

Yet anybody who's seen both movies can tell you the experience of watching one is nothing like the other. "The Matrix" affects a layer of cool, but at its heart it is a deeply sincere action movie about a young person overcoming self-doubt to challenge a cruel and unyielding system. By contrast, "Ghost in the Shell" is a meditative tone piece disguised as a cop thriller. Comparing the two is akin to saying "Mad Max: Fury Road" is an equivalent experience to "Stalker." That doesn't mean that "The Matrix" is better or worse than "Ghost in the Shell," but despite their similarities, they are distinctly different movies. But that leaves open the question: what is "Ghost in the Shell," really?

A dim image in the mirror

"Ghost in the Shell" is a movie about a woman named Motoko Kusanagi who works for a counterterrorism outfit called Section 9. Motoko is a cyborg, a powerful robot shell housing a human brain. Over the course of the film she and her coworkers come into contact with the Puppet Master, an infamous hacker who may be more than they appear to be. Yet the plot's twists and turns serve more as punctuation than as the heart and soul of the film. Its "ghost" (as Motoko would put it) lies somewhere else.

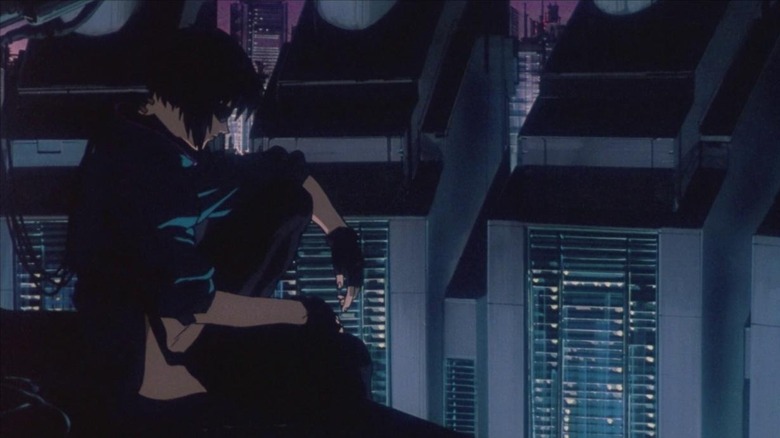

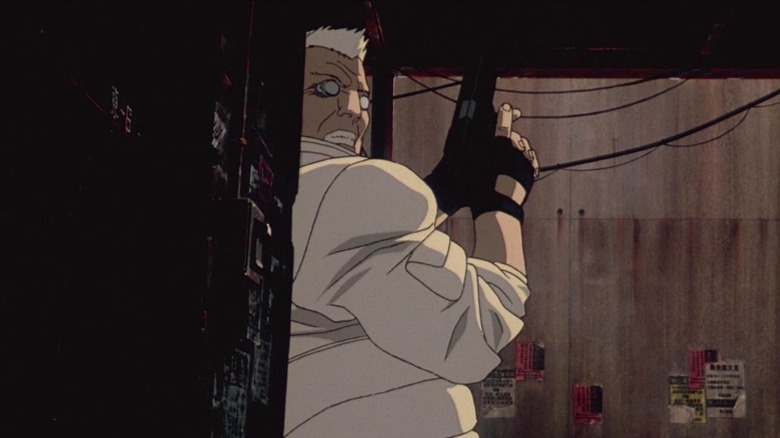

An early scene follows Section 9 as they pursue a criminal through the city streets. The sequence is framed from the perspective of the criminal; in a crumbling alleyway, he takes a moment to breathe and restock. Motoko does not have to breathe, because she is a machine. She falls from the sky, invisible, and effortlessly beats the criminal to a pulp. It's an exciting sequence, but also an uncomfortable one. Motoko is a tool, an agent of the state. She does her job thoroughly but dispassionately. What does it mean to be Motoko Kusanagi, whose body was bought in exchange for power? Motoko grapples with these feelings throughout the film, but where those feelings emanate from is itself a mystery. Her heart is constructed, her consciousness nothing but a spirit. That is "Ghost in the Shell."

It's just a drop in the bucket

"Ghost in the Shell" is a film about atmosphere (or as zoomers might say, "vibes".) Of course the big action beats are famous. But the sequence where Motoko dives deep into the ocean to better understand her connection to her body and consciousness is just as important. Throughout the film, the plot is repeatedly put on hold as the animated "camera" navigates streets of crumbling architecture without a single word of dialogue. The viewer is impressed with a sense of overpowering loneliness. If "The Matrix" is a film about revolutionizing society and the self, "Ghost in the Shell" is all about that creeping feeling of disassociation. It's about a world where corporations have won, governments dictate world affairs via covert ops squads, and the power of technology and the internet restricts us rather than empowers us.

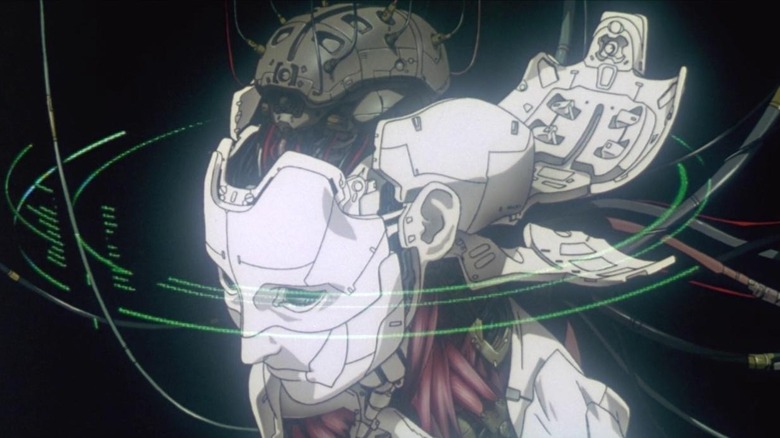

The tone of "Ghost in the Shell" is very different from its source material, despite sharing characters and certain plot beats. The film's director, Mamoru Oshii, is likely the one responsible. He made his name adapting the romantic comedy comic "Urusei Yatsura" into a hugely successful anime, but in the process, took such great liberties with the source material that fans sent him razor blades in the mail. Of course, Oshii was just the head of a convergence of Japanese anime talent. Future Oshii collaborator Kazunori Ito wrote the scripts, master animator Hiroyuki Okiura designed the characters, and Kenji Kawai composed a score nearly as influential as Shoji Yamashiro's for "Akira." Animator Mitsuo Iso, whose scenes in 1997's "End of Evangelion" would make him a legend, infamously prepared for the famous "spider tank" sequence in "Ghost in the Shell" by trapping a spider in a jar to better understand its reactions. Each of these figures was either an icon in the Japanese anime film industry, or was on their way to becoming one. "Ghost in the Shell" put them all under one roof.

Overspecialize and you breed in weakness

Of course, "The Matrix" is a historic production in its own right. The comics artist Geof Darrow ("Hard Boiled,") Chinese martial arts choreographer Yuen Woo-ping and the diligence of actors like Keanu Reeves and Carrie-Anne Moss were all essential in making the film what it was. If the film is more overtly populist than "Ghost in the Shell," with its rousing tale of a chosen one overthrowing a machine empire, that hardly means it is "dumbed down." The Wachowskis have simply always had different priorities as artists than Oshii. Laurence Fishburne's character in "The Matrix" takes great pleasure in explaining Baudrillard to mass audiences. By comparison, characters in "Ghost in the Shell" quote liberally from the Bible but never explain themselves. One film brilliantly condenses politics and philosophy into something anyone can understand, while the other is content to leave audiences grasping for meaning – because that uncertainty itself is the point.

For me, the closest ties between "The Matrix" and "Ghost in the Shell" have less to do with scene-by-scene references and more to do with ground-up creative decisions. In the "Animatrix" featurette "Scrolls to Screen," anime producer Hiroaki Takeuchi says of the Wachowskis:

"They took angles that we used quite a bit in Japanese manga, the direction of Japanese animation, Hong Kong wire action, and successfully combined them into a cohesive whole."

Similarly, Yoshiaki Kawajiri (director of "Ninja Scroll," another touchstone leading the way to "The Matrix") noticed the way the Wachowkis "edited their scenes was very similar to the way I edit my scenes. But," he says, "when you do it in live action it has a totally different feel."

In conceptualizing "The Matrix," the Wachowskis did something very impressive: rather than simply copying the art they respected, they internalized the lessons and built something inspired by that earlier material but not devoted to it. Both Takeuchi and Kawajiri clearly recognized how thoroughly the Wachowskis had digested the pacing and structure of manga and anime and came to respect them as artists in turn.

Puppet without a ghost

Furthermore, one of the defining aspects of the cyberpunk genre is cross-cultural exchange. Classics like the novel "Neuromancer" and the film "Blade Runner" were inevitably brought to Japan, leading to writers, animators and directors producing their own material, which in turn further inspired artists abroad. At its worst, this process leads to racist and thoughtless art that blindly copies the aesthetics of cyberpunk without considering its structure or themes. At its best, artists produce work like "Ghost in the Shell," which (just like "The Matrix") are in dialogue with their inspirations rather than subsumed by them. That isn't to say that films like "Ghost in the Shell" were made for global consumption, in the same way that some anime today are produced. Oshii continues to insist (in Brian Ruh's book "Stray Dog of Anime") that he has "never directed any of my animations thinking about how they might be made in the West." His films since "Ghost in the Shell" reflect that strong-willed artistic sensibility. Yet "Ghost in the Shell" was an international co-production with Manga Entertainment. It wears its global influences on its sleeve as proudly as "The Matrix" does.

Beyond visual homage, the greatest similarity between "Ghost in the Shell" and "The Matrix" may be that wire connecting the cyberpunk of the United States with the genre's evolution in Japan: the link between humans and machines. At first, "Ghost in the Shell" appears to be the exact opposite of "The Matrix" in being staged from the perspective of the Agents rather than a human resistance force. But "Ghost in the Shell" plays a trick on the audience. While Motoko is initially presented as the hero and the Puppet Master as the villain, it eventually becomes clear that the powers that be are threatened by both. The very existence of a machine with its own agency, a body that works against its owner, is threatening. In the same way that Neo's rebirth at the end of "The Matrix" marks a definite shift in the status quo of that world, Motoko's rebirth at the end of "Ghost in the Shell" represents the beginning of something new: a way of being that is complemented by technology, rather than restricted by it.

The net is vast and infinite

In today's era of anime supersaturation, "Ghost in the Shell" is no longer an exception. Today's teenagers flock to spectacles like "Demon Slayer: Mugen Train" and "Jujutsu Kaisen 0," adapted straight from the pages of Shounen Jump. Hardcore fans of Oshii advocate for "Patlabor 2: The Movie" and "Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer" as works that deserve greater attention from folks abroad. Oshii himself re-entered the fray last year with his first romantic comedy in ages, the bizarre and confrontational "Vlad Love." Any anime fan with an internet connection and a guide might have their fill of brilliant animated films without ever needing to touch "Ghost in the Shell."

Even so, "Ghost in the Shell" remains close to the hearts of those who remember it. A friend of mine, whose life was changed when he discovered the comic as a sixth grader, remembers shelling out $35 in the 90s for a VHS copy. Big shot Hollywood directors like James Cameron have insisted on its greatness. Speaking personally, the first time I saw the film, I found it to be an alienating experience. I preferred the likes of "Stand Alone Complex," the 2000s TV adaptation that incorporated more of the comic's humor and character. But in rewatching the film for this piece, there was something I couldn't place. Perhaps you could call it a haunting. More than camouflaged gear or spider tanks, there's a willingness to linger, to disquiet the audience. It's a quality that can be found throughout anime of the 90s and 2000s, including TV work like "Serial Experiments Lain" and "Texhnolyze." Perhaps that's the "ghost" the Wachowskis saw all those years ago.