The Daily Stream: The Tragedy Of Macbeth Renews Shakespeare As An A24 Horror Film By Joel Coen

(Welcome to The Daily Stream, an ongoing series in which the /Film team shares what they've been watching, why it's worth checking out, and where you can stream it.)

The Movie: "The Tragedy of Macbeth"

Where You Can Stream It: Apple TV+

The Pitch: An esteemed thane and his wife commit regicide in a bid for Scotland's throne and soon enter a downward spiral of further murder and madness.

In "The Tragedy of Macbeth," writer-director Joel Coen goes solo without losing a step. "The Ballad of Buster Scruggs," Coen's last film with his brother and career-long collaborator, Ethan Coen, had a limited theatrical engagement before it became a Netflix exclusive. With "The Tragedy of Macbeth" — which hit Apple TV+ on Friday — he's hopped to a different streaming service with a movie that seems like a shoo-in for multiple Oscar nominations when those are announced in early February.

"Macbeth," sometimes referred to as "The Scottish Play" because of a backstage superstition about uttering its cursed title aloud, has been performed on stage for hundreds of years. Some movie adaptations of Shakespeare's plays struggle to rise above their theater roots, but with "The Tragedy of Macbeth," Coen has crafted a proper film that marries the tell-me sensibility of the source material with the innate show-me sensibility of true cinema.

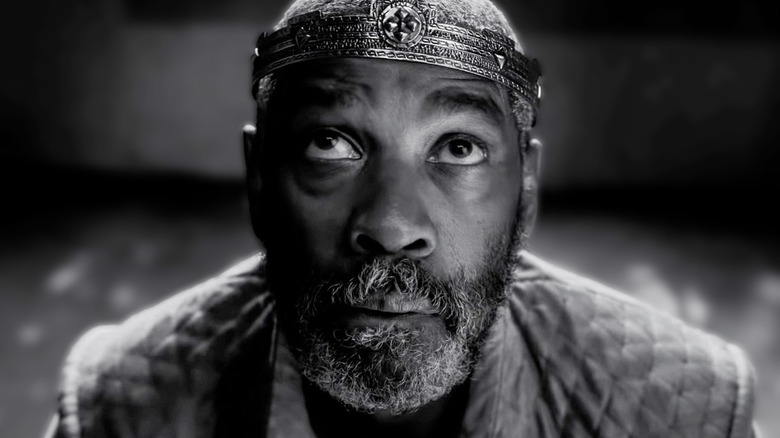

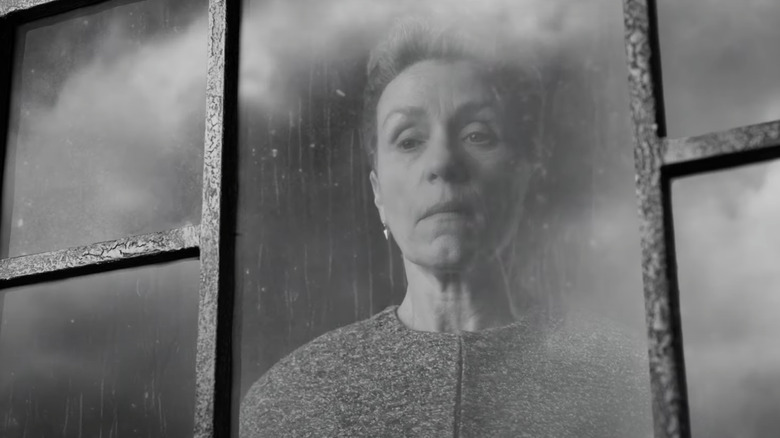

This movie is exquisitely framed, filled with arresting black-and-white visuals that will burn themselves into your brain and have you picturing them in your mind's-eye long after the credits have rolled. Bruno Delbonnel's cinematography has helped "The Tragedy of Macbeth" draw comparisons to German Expressionism and the work of Fritz Lang. It puts the faces of Denzel Washington, Francis McDormand, and other actors in close-up and often has them looking into the camera as they spout famous lines from the play.

Why It's Essential Viewing

"The Tragedy of Macbeth" is a striking evocation of Shakespeare as horror, one that is revelatory in how it forges a new appreciation for the power of the Bard's words. An atmosphere of foreboding pervades the film right from its opening seconds, where Kathyrn Hunter toggles between different vocal registers over a black screen, first whispering, then going guttural in a manner redolent of Mercedes McCambridge's demon-voice in "The Exorcist."

From there, Coen reels us into a mist-shrouded dreamscape, where crows circle overhead and A24 regular Ralph Ineson trudges across the sand. Hunter's three-in-one witch contorts her body in unnatural ways, more Gollum or Gerasene than woman, with her other identities — the two additional "weird sisters" — appearing only as silhouettes and reflections in the water.

Alex Hassell elevates the character of Ross to a more prominent, Littlefinger-esque manipulator. The interplay between light and shadow heightens the mood, as does Carter Burwell's score, a portentous mix of violins and bells, each knell of which summons us to hell, to paraphrase the protagonist.

Other parts of the musical and aural texture can only be described via impressions: footsteps, foghorn drones, faucet-like drips, and thunderous knocks. Burwell has scored many of the Coen Brothers' films, but in "No Country for Old Men," they chose to elide music, so his contribution was limited mostly to ambient sounds and "Blood Trails," the track that played over the closing credits. Here, he's in thriller mode.

"The Tragedy of Macbeth" was shot on soundstages like a highbrow answer to the pulp of "Sin City." Burwell described the film's look to IndieWire as more of a "psychological reality" than one with any precedent in locational reality. Production designer Stefan Dechant fills that world with geometric spaces. Focusing on the actor's faces against an economy of chiaroscuro backgrounds brings out the emotion of certain lines in an intimate, conversational way, in contrast to what you might see or hear in a stage performance where the thespians were playing to the back of the house.

Something Wicked This Way Comes

I read "Macbeth" in college and I've seen other adaptations of it over the years, including the Michael Fassbender version and Akira Kurosawa's "Throne of Blood." However, I never felt the full force of this play the way I did with "Hamlet," not until drinking in the vivid imagery of Coen's adaptation.

As a viewer, my pet peeve of late is the moment in movies and especially television shows, with their padded long-form narratives, when it breaks away from the rest of the ensemble for a scene with two mix-and-match characters having a heart-to-heart. We've seen moments like that proliferate all the more in the age of Peak TV, just as we've seen plenty of stories centered on antiheroes or outright villains, who inhabit a realm where "Fair is foul and foul is fair," much like Macbeth.

In the hands of the wrong screenwriter, the kind of scene I'm talking about often turns into a stagey, melodramatic monologue where it's just one character speaking and emoting while the other one plays the passive listener. "The Tragedy of Macbeth" is a reminder that such attempts at pathos stem from an older tradition of chamber-room dramas, laced with court intrigue.

Macbeth and Lady Macbeth conspire in the shadows and their stolen asides lead to the killing of a king. We're not just eavesdropping on therapy sessions where "the milk of human kindness" flows between scene partners. The stakes are life or death and the protagonist is someone whose mind is "full of scorpions" and whose "vaulting ambition" starts to unravel him almost immediately.

"To win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths." If it seems like I'm being liberal about quoting "The Tragedy of Macbeth," it just goes to show how this stripped-down reenactment, told in almost half the play's typical runtime, uncovers the raw potency of Shakespeare's soliloquies and dialogue. They're the source of all those quotes and phrases that you've probably absorbed like, "Something wicked this way comes," and, "Sound and fury, signifying nothing." Hearing some of them in their original context in "The Tragedy of Macbeth" is enough to send a viewer down a big Bard rabbit hole — starting with a same-day rewatch of this movie.