Why Robin Williams Was Furious At Disney After The Release Of Aladdin

Roger Ebert once described voice acting as what fading celebrities did instead of dinner theater. At one time, voice acting was relegated to only career voice performers, or, perhaps slumming live-action stars looking for an extra paycheck. This was long before the days of "Shrek," which smeared its celebrity voice talent all over its marketing, and the current era of animated features cramming as many well-known live-action actors as they can, advertising their presence with the enthusiasm of a sugared-up six-year-old touting the virtues of consuming a gallon of Coke after eating a vat of cake frosting. But this wasn't always the case. Back in the days of "The Jungle Book," it was considered something of a goof to hear Louis Prima singing, or George Sanders playing a seductive tiger; their names were most certainly not on the poster. The idea of selling an animated feature on its voice talent was considered backward.

There were recognizable names from time to time — "The Rescuers" starred Eva Gabor and Bob Newhart, comedians best known for TV. "Robin Hood" (1973) boasted Terry-Thomas and Peter Ustinov. — but while they were respected character actors, they were not marquee stars and they were not openly credited as they would be in a live-action feature.

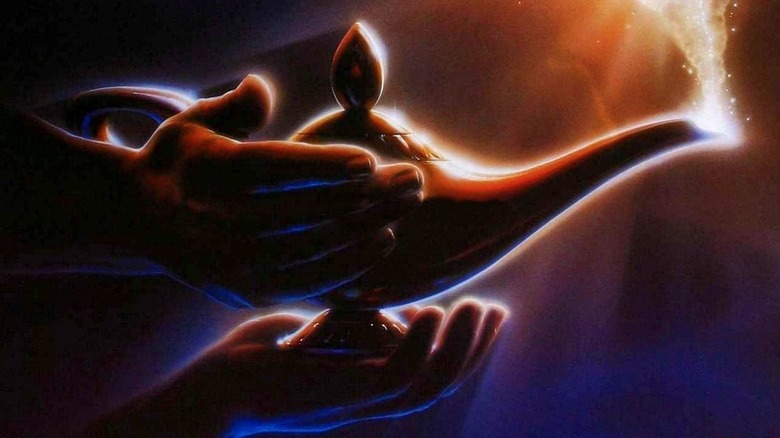

How did we get from exclusive voice actors and slumming talent to the inglorious commercial tallow wads like, say, "Peter Rabbit 2?" The flashpoint was "Aladdin" in 1992, starring Robin Williams, a highly advertised star who did not want to be advertised.

A Brief History of Disney Almost Failing

While "The Little Mermaid," released in the United States in November of 1989, is often credited as being the film that kicked the door open, ushering in an era of what it now called the Disney Renaissance, it was the modest success of 1988's "Oliver & Company" that showed the company giving its first true attempt to bank on voice actors that would be recognized by adult audiences. "Oliver & Company" starred Billy Joel (!), Cheech Marin, Bette Midler, and Dom DeLuise. Incidentally, Oliver was played by future teen heartthrob Joey Lawrence. It was about this time that Michael Eisner, then head of Disney, was making earnest attempts to turn the company around during a severe slump in the 1980s, and oversaw the production of "The Little Mermaid" and "Beauty and the Beast." The 1980s, recall, were a bad time for Disney in general, having put out a long series of flops amid rumors that their animation department may shutter entirely. "The Little Mermaid" saved Disney animation.

Also experiencing a slump in the 1980s — at least as far as movies go — was Robin Williams. As a standup comedian and sitcom star (does anyone under 40 remember the 1978 sitcom "Mork & Mindy?") Williams was an exploding star, packing theaters and headlining the Comic Relief charity tours. As a film star, though, Williams was still shaking off the stigma associated with his debut starring role in 1980's "Popeye," a truly bizarre flop from usually-reliable master Robert Altman. The '80s saw Williams starring in little-discussed films like "Moscow on the Hudson," "The Survivors," and "Club Paradise." It wasn't until films like "The Dead Poets Society," "Awakenings," and "The Fisher King" that Williams was able to prove himself as an actor. Disney also oversaw a Williams project around that time that lifted up his film career: Barry Levinson's "Good Morning, Vietnam," wherein Williams played real-life wartime DJ Adrien Cronaur. And let us not forget the significance of Steven Spielberg's "Hook" in 1991, wherein he played an adult Peter Pan.

But key to getting Williams involved in Disney's upcoming "Aladdin" film was a 20th Century Fox animated feature called "FernGully: The Last Rainforest."

FernGully: The Last Rainforest

"FernGully: The Last Rainforest" was released the same year as "Aladdin," but was in production long before. The film is about a human being who gets magically shrunk down to the size of a fairy and who meets a race of fairies that lives in a rainforest that is currently in the midst of being deforested. The human protagonist learns the error of his polluting, deforesting ways, and joins the fairies in revolt. Yes, critics noticed the similarities between this film and "Avatar." Heavily featured in "FernGully" was a rapping bat named Batty played by Robin Williams. The film's screenwriter wrote the role of Batty with Williams serving as inspiration and when the film's staff approached Williams to star, he — to their surprise and delight — agreed, citing the film's messages.

Put a bookmark on "FernGully." We'll come back to it.

At the same time, animators at Disney were also being inspired by Williams' standup persona, and were fashioning the Genie in their "Aladdin" film after him. Indeed, co-director Ron Musker began selling "Aladdin" to Disney's higher-ups as a Robin Williams vehicle before they even asked Williams to take part. Disney ended up luring Williams to play the Genie by creating some animations set to his old standup routines (animations you can see on the "Aladdin" Blu-ray special features). Williams reportedly loved the animations and agreed to play the Genie, and for scale ... but with one major stipulation: His name and his character could only be used in a maximum of 25% of the advertising materials.

Williams, it seems, didn't want to become a mascot or a figurehead, and wanted his performance to be part of a larger animated tradition. This is a romantic way of saying that Williams didn't want his name and character being used to push merch. "Don't use my voice to sell merchandise," he directly said. What's more, Williams was working with director Barry Levinson on a strange and ambitious antiwar film called "Toys" which was set to be released after "Aladdin," and he didn't want to oversaturate himself in film advertising. Disney agreed.

Then the horror began.

It's Barbaric, But Hey, It's Home

Disney was, of course, pleased that they landed a star as big as Robin Williams. But there was still the issue of "FernGully," which was still in production while Disney was working on Aladdin. One can only speculate as to the assumptions being made, but it seems Disney — specifically Jeffrey Katzenberg — might have been expecting Williams to drop out of "FernGully" when production on "Aladdin" began, likely so Disney would be the only ones with the actor in their corner.

As reported in Vanity Fair, Katzenberg reportedly found the animation studio where "FernGully" was being made and simply bought them. When "FernGully" moved to a new animation studio, Katzenberg bought that too, and would made regular "tours" to make sure that only Disney products were being made there. Yes, Disney tried to sabotage the production of a rival product. This has been par for the course for Disney for a long time, In 1997, they re-released "The Little Mermaid" on the same day as 20th Century Fox's "Anastasia." And who could forget their recent buying spree of LucasFilm and 20th Century Fox, putting all competition under their own umbrella. Now Disney owns both "FernGully" and "Anastasia." Williams, seeing that Katzenberg was trying to sabotage the film he was working on because he believed in it, was only further entrenched, refusing to leave the project.

It may have been this heat between Williams and Katzenberg that inspired Disney's "clever" workaround (read: deliberate violation, but still technically legal) of Williams' stipulation that his character only be used in 25% of advertising: Disney designed ads that wherein the Genie only took 25% of the frame. While not necessarily actionable, it was definitely a violation of the spirit of what Williams wanted. Disney also made God-knows how many toys of, and t-shirts with, the Genie. How this was meant to fit into the 25% clause, only the most skilled lawyers only speculate.

Umbrage!

In an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1993, Williams laid out how violated he felt, and how grossed out he was by Disney's use of his character as Burger King toys. They re-purposed his vocals for advertising purposes — exactly what Williams didn't want. One may say Williams was being naïve in asking the octopoid advertising kraken that is Disney to hold off on any kind of marketing, but Disney was very clearly violating Williams' trust regardless. A spokesperson for Disney, in that same Time article, pointed out that all ads were given to Williams for approval, and that he was just bitter for taking a low payday after "Aladdin" became an enormous hit.

Katzenberg reportedly tried to make good with Williams by gifting him a Picasso painting. Nothing doing. Williams was not having it.

The success of featuring Williams in "Aladdin" was seen immediately. The films made after "Aladdin" at Disney studios all featured a focussed supporting "wise-cracking" character played by a well-known comedy star: Jason Alexander in "The Hunchback of Notre Dame," Eddie Murphy in "Mulan," Danny DeVito in "Hercules," Rosie O'Donnell in "Tarzan." When Jeffrey Katzenberg went on to found DreamWorks in the mid-1990s, he brought a similar "big star" approach to that studio's animated output: Look at the all-star casts of "Antz" or "Prince of Egypt" or "The Road to El Dorado."

By the time "Shrek" hit, the coffin was pretty much nailed shut on Williams. The exact opposite of what he wanted to happen, happened.

And Apologies Were Issued

In 1994, after Jeffrey Katzenberg was fired from Disney, Joe Roth, his successor, apologized in the Los Angeles Times. Williams was placated enough by this to return to play the Genie in a straight-to-video sequel to "Aladdin" called "Aladdin and the King of Thieves." He reportedly got paid a million dollars for that one. Williams also go to play the Genie in a series of PSAs for Disney called "Great Minds Think 4 Themselves." This sort of film was much more in-keeping with Williams' desires. He also went on to work of Disney in other high-profile projects ("Jack," and "Bicentennial Man") and won an Oscar for his role in "Good Will Hunting," released by Disney subsidiary Miramax.

Williams, like the Genie, was let loose of his commercial servitude.

These days, however, we still have to gaze animated features in the eye and face down the tidal wave of cynicism of bankable on-screen actors being sold to an adult audience. Katzebberg started that. Williams tried to stop him. But the dam burst years ago.