Why Biopics Are Bad For Acting

From the moment it was first revealed that Nicole Kidman would be playing the iconic comedic figure Lucille Ball in an upcoming biopic, people had strong emotions on the subject. Aaron Sorkin's "Being the Ricardos" stars Kidman and Javier Bardem as Ball and husband Desi Arnaz, the faces of the iconic series "I Love Lucy," as they navigate their personal and professional lives. Kidman was all wrong for Lucy, so it was said: she doesn't have the comedic timing of Ball or her famously elastic face; she can't do the voice; Kidman's not the right age, and so on. The biggest criticism to emerge was that Kidman just doesn't look like Ball. How can she play someone so familiar to millions of people when we can't see her as anyone but Nicole Kidman?

This kind of reasoning is common when it comes to the much-discussed topic of biopics. The genre is a crucial backbone of Hollywood, a comfortably middlebrow cycle of tropes that appeals to wide audiences and has a delightful habit of attracting a lot of Oscar buzz. It's beyond a cliché at this point: if you want to win awards, you have to do a biopic. The numbers speak for themselves on this front. Since 2000, of the 105 men nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor, 45 were nominated for playing real-life people. For Best Actresses, it's 33, which includes Kidman herself, who famously won for playing Virginia Woolf in "The Hours." The Oscar buzz for "Being the Ricardos" emerged long before the cast was even announced because of course there had to be some sort of awards-adjacent anticipation for a biopic. Other factors barely seemed to matter. This cycle is simply so predictable, so thoroughly embedded in the culture of modern film that we don't really consider its impact. We don't seem to notice that biopics, and our stilted demands and expectations for them, have made acting a lot worse over the past few decades.

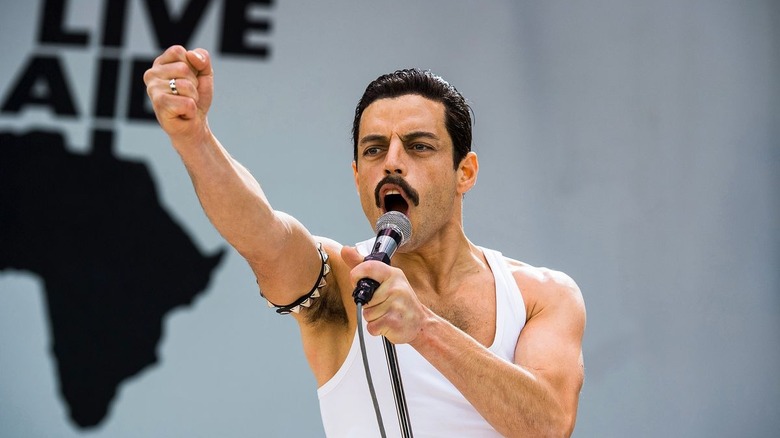

Acting is an incredibly difficult skill to quantify. Even for us critics, it's tough to explain exactly what makes a performance so brilliant and how another one that is so wildly different in style and tone can also be excellent. For many general viewers, the more subtle qualities of the craft aren't necessarily appreciated. You see this a lot when famously nuanced and subtle actors like Kristen Stewart are unfairly slammed as being "bland" or "not doing anything." Biopics, however, offer an easily digestible measuring stick for acting success. We have footage of the likes of Winston Churchill, Freddy Mercury, and Margaret Thatcher, so when we watch "Darkest Hour" or "Bohemian Rhapsody" or "The Iron Lady," we can compare and contrast. Did they perfectly replicate that ubiquitous and over-viewed speech or performance? Then that's a "good job," just give them the Oscar now. I'm not so sure it is good, though.

Acting Through Silicon

The biopic is an inherently limiting mold for telling a story. All genres come with their own tropes and boundaries and even the most well-worn cliches can be spun into something unique. With biopics, however, such things are seldom encouraged, both by the format and the surrounding demands of the industry that creates them. The biopic in its most known form is the epitome of middlebrow — undemanding and uninterested in pushing creative boundaries — yet it's never scorned in the way that, say, speculative fiction is. You know exactly what you're going to get when you see a modern biopic and that's sort of the problem.

We all know what to expect with a biopic: lots of flashbacks to a troubled youth, an inevitable descent into addiction that features a scene with furniture being smashed up, hackneyed reductions of the artistic process into narratively convenient flashes of inspiration, a worried spouse who exists only to stand by the hero (they're almost always a woman), and a triumphant climax followed by a coda of what happened next. It's so predictable that there are multiple hilarious parodies of the formula, most notably "Walk Hard." This narrative exists for a reason. It's easy to follow, it provides plenty of dramatic beats, and follows the traditional Hollywood pattern for a good couple hours of entertainment.

Because the expectations of the biopic are so narrow and heavily commodified, the actors involved don't really get a chance to be actors. They have to be impersonators, the big-budget equivalent of a Vegas drag show or a TikTok deepfake. To stray away from the agonizingly specific tics of their subject is to "do a bad job." The actor has to look exactly like the real-life person or they will face cries that they're not playing them properly. What that typically leads to is a hell of a lot of prosthetics. The obsession over aesthetic overwhelms the basic tenets of creating a lived-in character. Even some of our best actors have struggled with this. Gary Oldman may have won Best Actor for playing Winston Churchill in "Darkest Hour" but the heavy prosthetics that seemed to smother his face restricted the intensity and wit that makes him such a compelling onscreen presence. The result was a performance that was showy but not as layered or perceptive as his previous work in films like "Bram Stoker's Dracula" or "Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy." At what point does acting stop mattering when the focus is so heavily on silicon?

Pandering to Nostalgia

Most of this isn't really the actor's fault. You can only work with what you've been given, and the lion's share of these modern biopics are stifled by corporate interests. Biopics of major musicians are especially guilty of this. In order to attain the highly profitable and audience-demanded rights to those songs, the studios must adhere to the demands of the musicians' estates. If they don't want their subject to be shown in a salacious light or in a manner that could jeopardize their public image, then they won't sign off on things, regardless of matters such as historical accuracy.

"Bohemian Rhapsody" may be the most egregious example of this. That trainwreck of a film was so micromanaged by Brian May and Roger Taylor, the heads of the Queen estate and producers of the film, that it ended up rewriting Freddie Mercury's AIDS diagnosis to be a motivational twist for the Live Aid concert. The reality of Mercury's sexuality and personal life was softened into a PG-13-friendly cycle of judgment and implicit homophobia. Rami Malek may have won an Oscar for his portrayal of Mercury, but you can see how these expectations and limitations hindered his work: the over-sized dentures that often muffled his pronunciations; the inability to fully explore Mercury's wild past and sexuality; the terrible sound mix that left him out of sync with the music he was supposed to be singing. All of these roadblocks are rooted in those biopic issues, in that need to comply with industry and money-making demands. This was the movie the Queen estate dictated to the studio, and they got it.

One name that came up frequently as a "better" choice to play Lucille Ball over Nicole Kidman was Debra Messing, the "Will and Grace" star who has cited Ball as a personal inspiration. She even paid homage to Ball in an "I Love Lucy"-themed episode of "Will and Grace," which saw her recreate the chocolate factory scene from the show. The logic was that Messing in costume as Lucy Ricardo simply looked more like Ball than Kidman and that she had already proven her stuff. She could do a beat-for-beat copy of her gags so, surely, she could play her? There's something so disheartening about this mindset, the insistence that our understanding of the past should be frozen in time and wholly unchallenged. It's nostalgia calcified, a cycle of waxwork displays that do nothing but pander to our own rose-tinted view of the things we like. It's only a matter of time before one of these biopics just cuts out the middleman and uses a deepfake of the original star. That seems to be what a hell of a lot of people want.

Can Biopics Deviate From Hollywood Demands?

There are, obviously, exceptions to the rule of biopics but the best examples only tend to happen when the narratives deviate from those rigid demands. Marielle Heller's excellent "Can You Ever Forgive Me?" eschews a life-to-death story in favor of focusing on how writer and forger Lee Israel's crimes reflected the growing obsession with literary celebrity. That movie also benefitted from centering on a figure who was mostly unknown to the general public, allowing Melissa McCarthy to fully inhabit a real woman without having to worry that audiences would nitpick every choice she made. Bob Fosse's relentlessly bleak "Star 80," which tells the story of Playboy model Dorothy Stratten, dissected the cruelty of fame and its misogynistic roots, but was otherwise unconcerned with rehashing its subject's life. The magnum opus of biopics remains Paul Schrader's masterpiece "Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters," a blend of historical drama and literary adaptation that examines the life and politics of Japanese writer Yukio Mishima through his novels. All of these films feature incredible performances that prize emotion and authenticity over copycat routines and nostalgia-pandering.

Genres are supposed to be guidelines of sorts, creative frameworks for artists to build upon and expand. The biopic is what others make of it but, more than any other major genre in modern cinema, it is confined to blandness and risk-free scope for the sake of commercial success. How can you hope to make a great film when your only aim is to create a mimeograph of the past with all of the interesting details erased away? How can actors be expected to do their best job when it's more beneficial for them not to?

Alas, this rigid framework isn't in danger of disappearing any time soon. As far as Hollywood is concerned, it's working exactly as planned. "Bohemian Rhapsody" made close to a billion dollars worldwide and won four Oscars, including one for its leading man. It remains to be seen if this trend will continue with this season's awards run, or how "Being the Ricardos" will adhere to or subvert the formula. Why shake things up when the Oscars seem guaranteed?