The Visitor Review: The Musical Adaptation Is White Centricity Set To Average Music

In Tom McCarthy's 2007 film "The Visitor," released six years after September 11, 2001, a wall painting of the Twin Towers haunts the ICE detention center. Its presence denotes the racist and Islamophobic inhumanities that were exacerbated when the Bush administration waged the War on Terror in response to the 9/11 attacks. A critically regarded Sundance-selected drama, "The Visitor" has been noted by critics as one of the few humanizing portraits of undocumented people of color, though through a white male lens starring a white professor.

The recent musical adaptation playing at the Manhattan-based Newman Theater at the Public Theater does not specify its time period, although explicit mentions and visual reminders of 9/11 and the Twin Towers are omitted. In the movie, introspection about the 9/11 aftermath come in the form of "That's where the Twin Towers were" as a causal quote, the aforementioned painting of the Twin Towers on the ICE visitation center, and an ICE prisoner crying that he is not a "terrorist," which is a word scrubbed from the updated musical's book by Brian Yorkey and Kwame Kwei-Armah. The musical, intended to premiere in 2020 before the COVID-19 pandemic and released this October, is nearer to current events, closer to the memory of the Trump administration and an unrelenting Biden administration set to carry on the "Remain in Mexico" policy.

With passable music and lyrics by Tom Kitt and Yorkey (the duo best known for the Pulitzer Prize-winning "Next to Normal"), "The Visitor" finds trouble elevating a story that shows its age. The production has slick overall direction by Daniel Sullivan with the moody, but never imposing, lighting design by Japhy Weideman and blameless choreography by Lorin Latarro that avoids overwrought spectacle. But where Sullivan's direction falters is directing the intimacy that barely do justice for its core Arab American characters, especially with the material of the book.

Aging Badly

A widowed economics professor Walter (David Hyde Pierce, more of a fine actor than singer) is sleepwalking through his life. "Wake Up" is his first slouchy number about his dissatisfaction over his career and lack of human connection to the world. When he returns to his long-abandoned apartment in New York, he's confused to find an undocumented couple, Syrian-born drummer Tarek (Ahmad Maksoud) and Senegalese-born jewelry-maker Zainab (Alysha Deslorieux), residing there. Realizing they rented Walter's place from a scammer, they pack up. Clocking in their situation, the professor lets them stay at his place.

Walter forges a bond with Tarek and the latter educates him in finding the beat of the djembe drum, which becomes Walter's balm for his mid-life crisis. On a New York outing together, the NYPD falsely arrest Tarek for fare-jumping and eventually transport him to an ICE facility. Walter tries to alleviate the situation by hiring them a lawyer and eventually housing Tarek's visiting undocumented mother, Mouna (Jacqueline Antaramian, a somber and warm presence). Walter becomes their bridge of communication since Tarek's family could be compromised if they visit the ICE facility.

The production itself comes with a publicized production issues. The premiere was delayed to address concerns of Arab American representation by Tarek's original portrayer, Ari'el Stachel (famous for his Tony-winning role in "The Band's Visit" musical adaptation). Then the production was met with Stachel's eventual departure with stand-in Maksoud assuming Stachel's role.

White Centrism

The problems are endemic to the source material, even when it endeavors in expansive opportunities to give lyrics to its undocumented. But whenever Deslorieux and Maksoud are directed to share the stage and make eye contact with Pierce, they don't have a grip on their story. Pierce's character often stands like a sponge absorbing their words. He listens as Zainab (Deslorieux does an excellent job playing cautious skeptic) divulges a harrowing tale that includes separation and sexual abuse in "Zainab's Song (Bound for America)," a song intended to expand her character but the staging subjects her to a white guy's gaze.

"The Visitor" is most genuine whenever Pierce is absent on stage. Whenever Deslorieux and Maksoud face the audience without Pierce onstage, they fleetingly gain grip on their lives. In a major example, the strongest number "Lady Liberty," a sad duet expressing Lady Liberty's contradictions, occurs when Zainab talks with her mother-in-law for the first time and extinguish the tension between them (in this version, Mouna wanted her son to marry another person for a green card). Their conversational intimacy is staged over rails representing the ferry rails and low-lit blue to resemble sea waves. It was a wise decision to omit Walter, who was present in this scene from the movie.

Who Owns the Immigration Story?

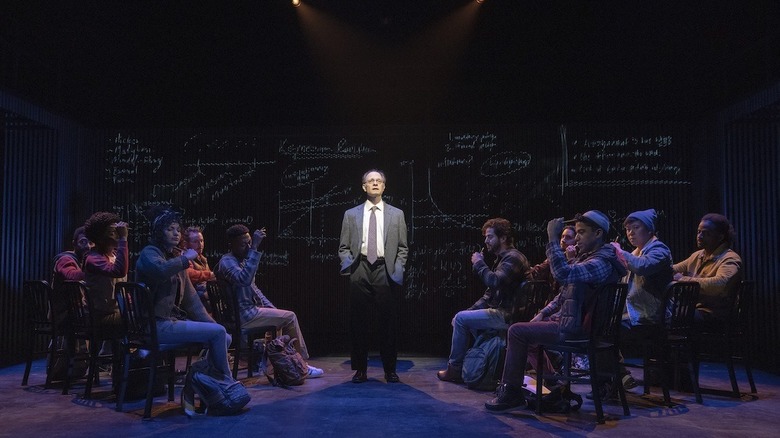

The final image (lifted from the movie's dated ending) tells you the arc of the stage musical: a white man in the spotlight playing an African drum, gifted by a man of color who was robbed of his musical life by a ruthless immigration system. Good thing an old white guy has found his rhythm to overcome a mid-life crisis, right? As staged, his three new friends stand in the background and fade, like receding phantoms in his headspace, with the professor loudly beating the drum.

If you're around in the Big Apple to visit the Public Theater, you'll find more of a pivotal experience with a production playing adjacent to "The Visitor" in the same Public Theater building: "Cullud Wattah," playing until December 12, a play spotlighting a Black family against the Flint Water Crisis and their intergenerational spirituality and resilience. Or regarding the topic of undocumented immigration, there's a profound experience found in the New York Theater Workshop 2021 production of "Sanctuary City" which follows two undocumented teens in the early post-9/11 era navigating the labyrinth of the oppressive immigration system entangled in their friendship and family issues. ("Sanctuary City" recently ended its streaming run and it is unknown as of now when it could resurface.)

"Sanctuary City" embodies one vital aspect of the undocumented immigrant storytelling: The story subjects most affected by the white supremacist immigration system have ownership, over their coping mechanisms, over their sorrow and anger, over telling their own story, over asserting their existence, interiority, and interests. Ownership is shakier for Tarek and Zainab in "The Visitor." Even when the couple briefly hold the spotlight and stage to themselves, the staging of the ending shrinks them into subplots in a white man's headspace. Their harrowing stories, though sincerely told, seem to exist for a white man to hear.

What is Being the 'Better Angel' About?

I have a distinct memory in the same Newman Theater two years ago, seated for "Soft Power," a reverse "King and I" musical by playwright David Henry Hwang. I happened to be sitting next to a white professor, the scholar who coined the "Soft Power" term that named Hwang's musical. He assumed I was Chinese, then guessed I was Taiwanese. I replied, I'm not Chinese and not quite something you should assume of any Asian stranger (my tone conversationally cheerful). He spoke to me about his adopted Chinese grandchild. He was an otherwise pleasant guy in person, though I wish that a better conversational scenario occurred.

"The Visitor" book updates its movie-adapted script to indicate that its economics professor isn't so pristine, and racial preconceptions exist along with his best intentions of allyship. The professor is introduced making a micro-aggression to a struggling student, and an internal monologue lyric later signifies he fears his new apartment companions may steal from him. However, the enduring focus on Walter's nice deeds pose him as a white savior figure and there's little allotted time for the audience to contemplate his faults.

And when "The Visitor" decides to get loud about its message that Americans should do some soul-searching and be the better angel, through the mouthpiece of Pierce's angry "Better Angels" number, it is too eager to give its leading man a halo. (The movie arguably reprimands Walter's naiveté in this scene when Mouna, played by Hiam Abbass in the film, stares at him in a stern close-up to extinguish his outburst at ICE agents.) This scene highlights best that "The Visitor" is about a white man's secondhand suffering when the story is about the firsthand sufferers.

It's easy to see how "The Visitor" may charm less critical theatergoers. In its dramatic non-musical parts, the direction not unlike the original movie steers the story in a tantalizing low-key direction where not much is spoken aloud. Walking out of the theater, I suspect old white theatergoers would see themselves in Walter, the "better angel."

Walking out of "The Visitor" left a rather eh impression for me and a hope that its otherwise moving leads and ensemble will find better theatre material unsaddled by problematics. Then the more I sat on it, the more frustrated I was that "Better Angels" could only muster the "good, deserving American immigrant" as its prime argument for the humanity of the undocumented. It is a message relatively unevolved from the movie's commentary, as if the musical can't unlatch an immigrant's humanity from American status, the narrow metric of "who deserves to stay, and who doesn't." Walter's outburst of a lyric, meant to be absorbed at face value, "This man is an American, in all that matters most" comes from someone who means well but is short of imagination.

"The Visitor" is playing at The Public Theater in NYC until December 5, 2021.