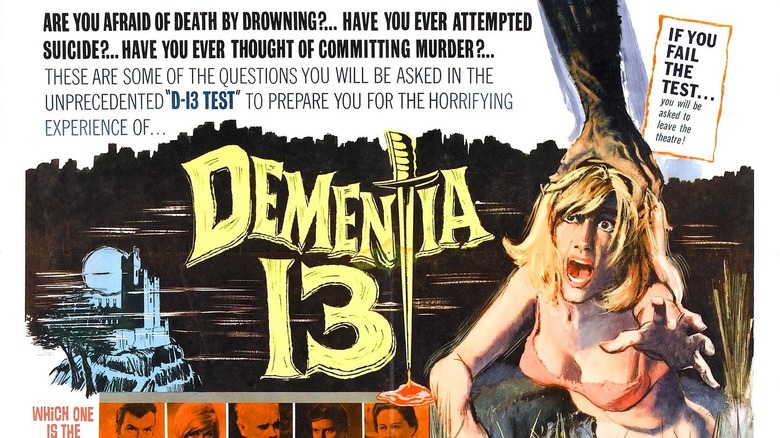

The Legendary Francis Ford Coppola Revisits Dementia 13, His Low-Budget Horror Debut [Interview]

Legendary filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola was around 21-years old when he made his feature directorial debut with "Dementia 13." And decades later, he has revisited the Roger Corman-produced film to release a remastered director's cut of his playfully dark horror movie. Upon initial release, scenes were added and cut not to the filmmaker's liking. Now, Coppola's original vision is both restored and enjoyable.

When the director started shooting his first feature film, he didn't have a script. He'd stay up all night, drinking coffee and typing out pages. He was barely beyond being theater student, one who had directed plays and a few short films at UCLA, but was still a decade away from making "The Godfather" and other '70s masterpieces. Today, he still doesn't know exactly where the story of "Dementia 13" came from. He just wanted to tell a mystery that "was a rip-off of a rip-off of a rip-off" for Corman.

Recently, "Call Me Francis" Ford Coppola talked to /Film about his days in Ireland making the film, and why he doesn't see himself as the master the world sees him as.

I don't feel like a master with cinema.

Hi Mr. Coppola. How are you?

Hello. Please call me Francis.

Francis, thank you so much for your time. Years ago, you said at Festival of Disruption, people use the word "master," but you always see yourself as a student. As a student, what have you been studying lately?

That's a big question. I mean, yes, it's true. It's basically with life, we're all students, because we're passing this way, this adventure once, and we're learning as we're going how to live it. But cinema, especially, cinema is only what, 120 years old, or maybe something like that, 180 years old. So, there was a recent tendency because of a play called Master Class about 30 years ago, which was really about Maria Callas, and everyone glommed onto that phrase, you'll do a masterclass.

I don't feel like a master with cinema. I think it's such an amazing form and something that one could be so enthusiastic about that I feel more like a student of cinema. I love to talk to young people about cinema, about art, about the great movies that have been made in the past, but I refuse to be labeled the master, because my conversations with young people are more like a student to student discussion. How old are you?

I'm 30.

In this conversation we're going to have, I'm going to learn as much from you as you're going to learn from me. I can consider it more a student to student conversation. And in terms of what I'm learning about now, I have a rule that every night when I go to bed, I try to be reading something. It could be a biography, it could be a great work of fiction, it could be anything, but I read myself to sleep. And I always like to think that I'm choosing a subject matter in what I'm reading that has nothing to do with whatever I'm working on so I get a break from it.

And when I go to bed, I've got this friend waiting, which is my book. And usually, it's not about anything that I'm worried about, or I'm working on, or I'm writing, but the irony is that anything I choose seems to be very pertaining to what I'm working on, which means that I must be searching subconsciously for ideas or nourishment when I'm working and I'll find it in anything. Right now, I'm reading a book that's, I read a lot of long, incredible works of fiction. I read all of Proust. I would say, it wasn't what I would like when I was your age. But in the last 10 years, I read myself asleep and I read all the five Proust novels. I've read all the longest works of fiction. And there's a Chinese novel called many titles, but it's comes from about, I would say 17th, 18th century in China, before the great decline of Chinese story.

It's called, The Dream of the Red Mansion, or, The Story of the Stone. It's got to be 2,000 pages long and I'm in about 35% of it. And I'm reading this book written by what is the main character in the story, who was a young kid, about 13, who lived in an incredible garden. Of course, his father was somehow associated with the Emperor. And in this garden of this book, he's surrounded by girls, all his cousins and sisters and the children of the concubines of his father. So this 14 year old boy, when it starts, is just doted upon by all these wonderful girls. And later in life, when he started to write the book, he said he wrote it because he had met these extraordinary girls who were so lovely and brilliant and their games during the day, was to write poetry together.

And somehow, I'm reading that now, and I'm finding it's changing my life. I'm sort of saying that makes sense to go around and make all these nice places in your garden, give them wonderful names like the Pavilion of Parting, or the Steps of Sincere Hello, or the Sanctuary of Ancient Friends. So I'm going around now and naming all of these places where I live and when people say goodbye, I say, "Come with me into the Pavilion of Parting and let's say goodbye there." So that's what I'm reading and how I'm learning from it.

I Was Just a Kid.

You weren't too far from my age during your Roger Corman days. Is that a time you look back on very fondly? Was it an exciting time?

Yeah. Well, to understand me as a 20 year old, first of all, I was really poor. I was the bad boy in the family, a bad boy not because I was bad behavior, but I wasn't so good in school. And, I had by comparison, a brilliant older brother who was also totally handsome and great in school and a leader, but he was very kind to me. So I was not really considered college material. And so when I did go to the UCLA film school, I lived on a dollar and a quarter a day. I remember very well. It was 25 cents for breakfast, 50 cents for lunch and 75 cents for dinner. And that's when I ate so many Kraft macaroni and cheese there, which cost 19 cents in those days, that I got.

So when I got a job with Roger Corman, literally, I waited by the phone hoping that I would... I had applied for it, hoping I'd get a return call, but knowing that I hadn't paid my phone bill and was going to get cut off any moment. So getting the job with Roger was a lifesaver. And of course, I learned I was able to learn so much because I gave it everything. I would stay up half through the night to do something that Roger had asked me to do and I would wash his car. I wanted that beginning one day [to lead to] my dream, which frankly, was that I might be able to be in the movie business, as an assistant director or something. I had directed plays, but I didn't know that I'd ever make that, because no film student ever had. Film students when they got degrees from UCLA or USC, inevitably went to work for the USIA or make films for the government.

But to break into that sanctuary of professional filmmakers, hadn't been done. So of course, that was my aspiration. I worked really hard at Roger's. I mean, I basically became his assistant and ultimately, then he did take me. He said to me, "Do you know anyone who knew how to be a sound man?" And I said, "I could do it." And I read the manual on how to make sound in those days for movies and Roger deemed to take me on a picture called, "The Young Racers," as the sound man and kind of an all purpose assistant, which was how I learned so much from Roger. Roger always made two movies when he went off for his company, which was AIP, [which] was not his company, [but] the one sponsoring him. Since they paid for all the setup, he'd then made a second film for himself, because it was very cheap. It was all, everything was there.

And so when he got called back to do a film called, "The Raven" with Boris Karloff and Peter Lorre, very funny movie, everyone working for him knew that there'd be another picture if someone could dream it up and get him to bless it. And so, I wrote a page that I showed Roger and ultimately, I won the sweepstakes and he said, "Okay, you can make that if you can make it for $20,000." And then, I would suggest going to Ireland to make it, because everyone speaks English. If you go to Yugoslavia, everyone speaks basically Russian for language, so go where, you know how to speak English, so go to Ireland." So basically, that was how I got this wonderful chance and how a poor theater student to make a first film, which he named it, "Dementia 13," because there had been a film called "Dementia" and he thought that if he named it "Dementia 13," every 13th day of every month, someone would maybe book the film.

Roger was very smart about those kinds of things, how to make money. So I went to Ireland, and I didn't even have a script. I had this one page. I had to write a script while I was shooting it. I was writing it during the night on mimeograph masters so that we could roll it off and give it to the cast. Of course, Ireland had the blessing of a lot of wonderful actors who have been associated with the Irish theater there, among which was Patrick Magee and Eithne Dunne and these Irish Abbey theater. The people in Ireland were incredibly welcoming and kind to me. I was just a kid. I was 20, 21 and they were, the Irish people were very poor in those days. They were very kind and very warm and wonderful people. I remember that.

I Better Hurry Up.

When you revisited the movie, how did you see yourself as a filmmaker at that time?

Well, all young filmmakers in those days were in awe of Orson Welles and "Citizen Kane." There was a trilogy of young filmmakers that we looked up to, Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, and John Frankenheimer. And each of them, those three, are still great when you think what they, for different reasons, what they accomplished. So with that inspiration, those photographers always had a certain juicy kind of photography with beautiful framing, shooting through things and depth of field, where with the compositions were very strong.

I am told that "Dementia 13" was one of the early films that Stephen King liked when he was young. Just a bit of, I don't know if it's true, but an incredible master like Stephen King and the fact that he might've been... "Dementia 13" was essentially really my first feature film that I had ever made and I was thrilled to have the opportunity to do it.

And there was an editor that Roger recommended to help me, who I would want to credit, Mort Tubor, and he really helped "Dementia." I learned a lot from how he dealt with the scenes that I shot. I think a lot of what's good about "Dementia 13" was the contribution of that editor. At any rate, film like life, you learn as you go along. As we go, we learn. And the trick of people who have the right attitude, is to realize that and to make use of what you learn and to rethink yourself and rethink your opinions and not be like, this is the way it is, or I'm going to make films this way.

And also, every one of us, me, you, everybody on earth, is a unique individual. So if you're going to make art, let it be personal. So there are things in "Dementia 13" that I was trying to copy, "Psycho," or some great filmmaker, Kubrick or Welles, but there are a few things that were uniquely me. And good or bad, one of my flaws I think is that I was a theater student in the fifties. So to me, the Gods of theater were three. It was Marlon Brando, Elia Kazan, and above all, Tennessee Williams. So I feel that my flaw, and what's even less than I wished it were, is some of the dialogue I was writing in imitation to Tennessee Williams. I don't know, Tennessee Williams was a poet, was a gifted writer for the ages and maybe I might eventually have some ability as a writer, which is what my fondest dream is, but it wouldn't be imitating Tennessee Williams.

Somehow I have to find what I can do. I can be inspired by Tennessee. I can even attempt to steal from Tennessee Williams, but it has to go through me and come out some way else. And I'm still struggling with that. I tend to think of myself as a good director who has a less good writer under contract that I always use, who is me, and I want to improve it. And writing is something you can improve if you write every day and you really are honest with yourself. Eventually, it's like poetry. Eventually, you find your voice, but my voice... Whereas, it will be inspired by greats like Tennessee Williams, and Thornton Wilder, even less great in my opinion, Eugene O'Neill, but it will be something that I evolve eventually. I better hurry up, because I'm 82 now and I'm still trying.

How'd you feel when "Dementia 13" was originally released?

I always, when you finish a movie, you know that it's going to come out and it's going to be judged by it's good or bad, and it's going to have to live with that judgment through its life. So the moment before a film is released, of course, you're getting all this advice from the people who have invested in it, or the people, and inevitably, the advice is too long, too much of this, or too much of that. So very often, later on you realize that it maybe wasn't too long, or maybe it was. I always discover later on that my earlier cuts were more right than wrong and what everyone was asking me to do was more wrong than right. And so that's why today I don't hesitate to change.

Like, the new version of "Cotton Club" called, "Cotton Club Encore," is much better than the "Cotton Club" and the new "Godfather III," which is called "Godfather Coda: the Death of Michael Corleone," is much better than it was. So I think also Dementia 13 in this version, which is a little different than what Roger put out, because he felt it should have more killings and felt it should be longer. I feel this version of "Dementia 13" is more worthy of being seen and has some good parts and some good moments that I would endorse and that I'm proud of.