The 30 Best Heist Movies Of All Time

Heist movies transcend genre. You can have frivolous, fun heist movies like "The Italian Job," or heartfelt, straight-faced ones like "Point Break." The heist itself can be meticulously planned and meditative, like the one in "Inside Man," or it can fall apart before it even begins, as in "Good Time." Either way, there's little in cinema more satisfying than watching a complex robbery come together — or seeing it crumble into pieces.

To be clear, this is a list of heist films, not movies about con artists. "The Sting," "The Brothers Bloom," and "Gambit" are all brilliant, but they don't contain the standard tropes — planning the mission, gathering a team of colorful experts, and so on. As a result, their big crimes feel more like magic tricks than actual heists. Further, for our purposes, the heist — or heists, if there's more than one — needs to be the focus. "The Usual Suspects" is an excellent movie, but the crimes in it are almost incidental; it's more about the characters and the twisty plot than the jobs themselves.

In the following movies, the plots revolve around robberies, which the films either build to, or which serve as major turning points in the stories. In either case, these are our picks for the greatest heist films of all time, ranked from worst to best.

30. Dead Presidents

The Hughes brothers' second film instantly throws you in the deep end, showing us a group of thieves preparing to rob an armored truck, before flashing back to the events that led protagonist Anthony (Larenz Tate) down this path. "Dead Presidents" often feels like it's veering off into a very different direction, as Anthony falls in love and joins the army just as the Vietnam War breaks out. This could have made the heist seem like something of an afterthought, but instead it informs the characters, explaining their later actions without the need for a massive exposition dump.

Tapping into the poor treatment returning veterans faced after Vietnam and the difficulties they had rejoining society, the directors take their time establishing an assortment of colorful characters. Despite standouts like Keith David's one-legged bookkeeper and Freddie Rodriguez's pyromaniac, the most moving performance comes from, of all people, Chris Tucker, who plays an easygoing friend of Anthony's who turns to heroin after his wartime experience. "Dead Presidents" is just as angry and vital today as it was upon release; it doesn't make excuses for the protagonists, but Tate's final outburst still resonates as a powerful indictment of how society treats veterans.

29. Inside Man

On the surface "Inside Man" might look like a simple picture-for-hire for director Spike Lee, but it turns out to be a slick combination of "Heat" and "Ocean's Eleven." What sets it apart from other heist films is how the details of the robbery remain a mystery. Employing a playfully non-linear timeline, Lee jumps between the heist itself and its aftermath, showing both how the enigmatic mastermind Dalton (Clive Owen) and his gang hold up the bank, as well as detectives Frazier (Denzel Washington) and Mitchell's (Chiwetel Ejiofor) attempts to piece together the details after the fact.

The structure immediately grabs your attention, and with the hostages and robbers all dressed in the same outfit (painting overalls, masks, and goggles), the gang members' identities are a mystery to both us and the cops. As we see cops interrogate each of the hostages, it quickly becomes apparent that the police are trying to work out who is a criminal and who was a bystander. Similarly, the thieves' motivations are left intentionally obscure, as is the shady personal history of the bank's president (Christopher Plummer) and his professional fixer (Jodie Foster), making life even harder for the detectives.

While the robbery itself is played straight, "Inside Man" is surprisingly light-hearted, and a much wittier film than it needed to be. It's best enjoyed as a kind of puzzle, with misdirects and red herrings relentlessly thrown up on screen, keeping both us and Washington off the scent until the multiple reveals.

28. The Taking of Pelham One Two Three

In this tough as nails 1974 thriller, Walter Matthau stars as a doggedly determined detective who negotiates with four gunmen who hijack a subway train (passengers and all) and demand one million dollars from the city for its release. Robert Shaw delivers a coldly clinical performance as an enigmatic, ruthless mastermind, while his gang (Martin Balsam, Hector Elizondo, and Earl Hindman) each make their characters distinct. Elizondo's psychotic loose cannon is especially memorable.

With the use of color-coded aliases, (Mr. Green, Mr. Brown, etc.) this is a definite precursor to "Reservoir Dogs," and Matthau's performance is a perfect blend of the tough guy persona that he perfected in films like "Charley Varrick" and the comedic roles he took later in life. Here, he plays Lieutenant Zack Garber with a heavy dose of irony as he negotiates with Shaw's implacable thief, and while "The Taking Of Pelham One Two Three" sometimes veers into comedy (especially Jerry Stiller's detective, as well as the final punchline) this only serves to make the sudden bursts of violence all the more shocking.

27. The League of Gentlemen

This old-fashioned British heist film is different from the film noirs of the same era in that it spends the majority of its runtime delving into the characters' backstories and their preparations for the heist. The robbery's mastermind, Hyde (Jack Hawkins), debuts emerging from a sewer in a pristine dinner suit, a visual that playfully and concisely sums up the film's central focus on class and respectability.

Hyde recruits a variety of fellow veterans-turned-petty-criminals (including three played by Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, and Nigel Patrick) to execute a robbery that's been planned with military precision. Each member of the gang has their own special set of skills that they use during the heist, and the climax is thrillingly action-packed. The gang is clad in trench coats and gas masks, brandishing machine guns and chucking smoke bombs, while Hawkins deploys his baritone voice to threaten the bank tellers.

Rather than featuring a daring escape or having each character brought down by their fatal flaws, the end of "The League of Gentlemen" is rather muted, but on a rewatch that becomes part of the fun. As in the best film noirs and many of the best heist films, the criminals are not foiled by the police or their own mistakes, but instead random chance — in this case, nothing more than a little boy and his innocent hobby.

"The League Of Gentlemen" is a witty, charming film that never feels twee or mannered, chiefly thanks to the grounded performances of its ensemble cast. Hawkins in particular stands out, imbuing his character with just the right balance of dry humor and gravitas.

26. Widows

Steve McQueen's one attempt at a pure genre piece so far, this remake of the Lynda LaPlante series from the '80s is one of his most satisfying (and rewatchable) films. It is a timely and relevant slice of feminist cinema that doesn't rely on condescending "girl power" ("Ocean's Eight" this is not).

Viola Davis, Elizabeth Debicki, and Michelle Rodriguez play women who come together after their husbands are killed in a heist gone wrong. Completely out of their depth, they nevertheless resolve to carry out a robbery in order to repay the man their husbands stole from. Davis utterly owns the film as the de facto leader, while Cynthia Erivo proved she was one to watch as the babysitter-slash-driver.

The beauty of "Widows" lies in the meticulous way the women prepare for the robbery, casing the target's house and practicing with different weights of money. It's an excellent depiction of non-criminal characters planning a heist, and whether they're acquiring guns, buying a getaway vehicle, or doing some amateur sleuthing, the makeshift way each of the gang gets ready feels incredibly plausible. What goes unsaid is how the women are completely discounted as being a threat due to the simple fact of their gender (their one male ally is taken out of the picture very early on) and how they use this to their advantage, even pretending to be men during the actual heist.

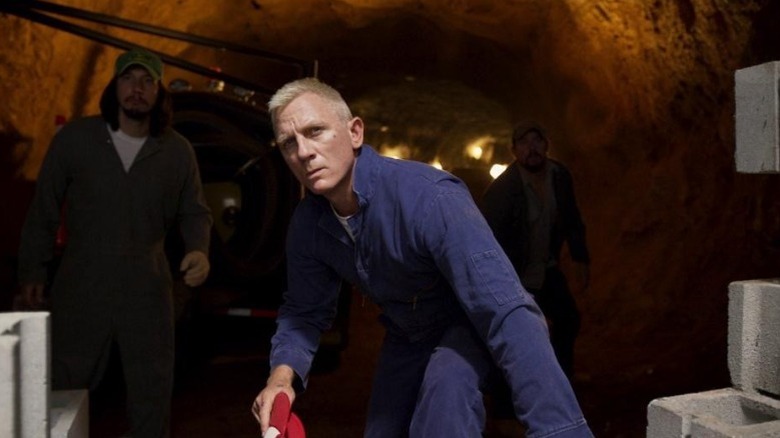

25. Logan Lucky

Soderbergh's rough and ready heist film (referred to as "Ocean's 7-11" in the film, making for a nice self-referential moment) is a lot of fun, serving as a neat subversion of the tropes Soderbergh used in his earlier movies. Channing Tatum and Adam Driver play an unlikely pair of brothers who plan to rob a NASCAR racetrack, while Daniel Craig is a revelation as a flamboyant explosives expert — a role that almost certainly played a part in him getting cast in "Knives Out".

Soderbergh could so easily have turned "Logan Lucky" into a sneering parody of its southern characters, but instead plays things perfectly. All of the elements of small town life that lead everyone to underestimate Tatum and his gang help the plan rather than hinder it. The lack of cell phones, the corrupt prison system, and Tatum's simple nature mean that the FBI are unable to pin down the specifics of the burglary. "Logan Lucky" is a fun and surprisingly touching film — even Seth McFarlane's irritating British accent can't ruin it.

24. Bellman and True

An unheralded gem of British cinema, "Bellman and True" is a low-budget heist film from George Harrison's Handmade Films. Unassuming, alcoholic Hiller (Bernard Hill) is a computer programmer who is abducted along with his stepson (Kieran O Brien) by a gang of bank robbers who need his expertise to deactivate the alarms.

It's a stripped-back, very British (the gang drinks tea with toast after the robbery) crime thriller but with none of the macho posturing you get from Guy Ritchie or Matthew Vaughn. Aside from the main characters, the gang's members aren't even given names. Instead, they are just referred to by their roles during the robbery: the Guv'nor, the Bellman, the Wheelman, etc. The heist is an incredibly tense sequence that sears itself into your memory thanks to the grisly fate of one unfortunate member of the gang who gets stuck in the elevator shaft. Their frantic escape climaxes with the getaway driver trying to force his car through a tiny gap.

Few heist films delve into the amount of preparation that goes into the planning of the robbery quite as meticulously as "Bellman and True." Director Richard Loncraine shows the financing side and the details of the plan in painstaking detail. The idea for the robbery is ingenious: The gang deliberately sets the alarm off repeatedly and convinces the authorities that the alarm is faulty while they break into the vault. It's mundane and hardly as glamorous as the "Ocean's" films, but it has a bleak, fatalistic charm all of its own. Hiller's relationship with his son is quietly touching.

23. The Lavender Hill Mob

Our first entry from Ealing Studios, "The Lavender Hill Mob" is a light comedy with an ingenious premise and a charming central performance from Alec Guinness. Here, Guinness plays the unassuming bank official Henry Holland, who concocts a fool-proof plan to steal the gold bullion he has doggedly protected for his entire career. When he meets souvenir manufacturer Albert Pendlebury (Stanley Holloway), Holland hatches a scheme to ship the gold out of the country by melting it down in Pendlebury's foundry and turning it into paperweights of the Eiffel Tower. With a pair of professional thieves (Sid James and Alfie Bass) as accomplices, Holland and Pendlebury execute the perfect robbery; however, as in many heist films, the aftermath proves problematic.

Full of the dry British humor that was Ealing Studios' mainstay, Charles Crichton's film almost serves as a curative to the blacker-than-black comedy of "The Ladykillers." In the film's stand-out scene, Holland and Pendlebury frantically pursue a group of schoolgirls down the steps of the Eiffel Tower, running round and round the staircase until they're giggling hysterically like a pair of children. That's the tone of the entire film: chaotic, childish, and innocent mania that belies a genuine sense of urgency and suspense.

A huge influence on "The Italian Job," "Hot Fuzz," and practically every other British crime comedy that followed, "The Lavender Hill Mob" is one of the most feel-good heist films of all time. It's a lightweight movie, but you'll still find yourself hoping that Pendlebury and Holland will get away with it every time you watch.

22. Charley Varrick

A Don Siegel film with more than a hint of Elmore Leonard about it, "Charley Varrick" follows a resourceful bank robber/crop dusting pilot who finds himself out of his depth after his latest heist when he discovers that he has inadvertently stolen from the Mob, who send a sadistic hitman (Joe Don Baker) to retrieve the loot.

Walter Matthau couldn't be further from his comic roles in "The Odd Couple" or "The Fortune Cookie" in a return to the dramatic roles he played early in his career. As the eponymous Varrick, he gives a dour, world-weary performance, underplaying his character while still keeping his sense of irony and conveying an awful lot with little more than a baleful glance.

Unlike most heist films, "Charley Varrick" isn't that concerned with the pivotal robbery itself, which is slick but chaotic with a high body count (This is a Don Siegel film after all). The majority of the film follows Varrick as he puts his escape plan into action while outwitting the Mob. Siegel only ever shows us glimpses of Varrick's plan, so when all the pieces fall into place in the final scene, it's immensely satisfying.

21. The Town

Ben Affleck's sophomore directorial effort is one of his very best films, albeit a much simpler one than his debut feature, "Gone Baby Gone." Affleck plays Doug, the leader of a professional gang of thieves that operates out of Charlestown. Clinical and efficient, the crooks' well-oiled machine hits a snag when Affleck falls for the cashier at their latest target (Rebecca Hall).

There are similarities between "The Town" and "Thief," but the former doesn't have the stoicism or the cynical edge of Mann's film. What it does have is a great sense of urgency and a palpable feeling of desperation and claustrophobia. Caan's safecracker was an outsider, while Doug is thoroughly embedded in the local criminal culture. However much he might want to leave this life behind, he has roots in Boston; there's even an FBI agent (Jon Hamm) intent on putting him behind bars.

Like the heists themselves, "The Town" unfolds with an impressive, brutal efficiency, sketching out character backstories quickly and concisely. Jeremy Renner gives a career-best performance as Doug's volatile second-in-command. He's quick-tempered and a little unhinged, but Renner brings a warmth and pathos to the character. The scenes of the gang undertaking their heists with surgical precision are thrilling, and the editing is frenetic but clean; you never lose track of what's going on, even when all chaos breaks loose. There's a muscular dynamism to these set pieces, with each robbery getting a distinct look thanks to the creative disguises the gang wears. It all builds to a nail-biting finale and the group's most ambitious score yet: robbing Fenway Park, "the cathedral of Boston."

20. Ocean's Eleven

Too often dismissed as lightweight and therefore somehow not worthwhile, Steven Soderbergh's slick heist film heavily influenced the way that heist films are edited and shot. If there hadn't been an "Ocean's Eleven," there wouldn't be a "Now You See Me" or any of the other pretenders. One of Soderbergh's major talents has always been his fluid use of editing, and here his cuts make what could be a convoluted plot seem light, breezy, and incredibly cool.

There's a misconception that because a film is fun and mainstream, it shouldn't be taken seriously, but "Ocean's Eleven" succeeds precisely because of Soderbergh's precision behind the camera. It takes a lot of effort to make something seem so effortless. While its sequels would prove increasingly self indulgent and contrived, "Ocean's Eleven" manages to juggle its cast expertly, giving each of them their moment to shine — no mean feat when you've got a cast of 11! Just as slick today as it was in 2000, "Ocean's Eleven" still stands up as one of the all-time coolest heist films.

19. Thief

In Michael Mann's masterpiece "Heat," Neil McAuley (Robert DeNiro) says, "Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner." Mann's debut film, "Thief," might not be as wholly satisfying as his later feature, but it's a much more potent exponent of this ethos, and all the more poignant for it. It's also Mann's purest heist film, as slick, efficient, and economical as its protagonist.

James Caan plays Frank, a newly released safecracker who dreams of an idyllic life, a fantasy that he must discard once his enemies try to use it as leverage. A spiritual successor to the mythic heroes of Jean Pierre Melville's existential crime films, Frank is a stoic, consummate professional, as evidenced in the sequences showing him at work. Frank's methodical approach to his job impresses a local mob boss (Robert Prosky, equal parts amiable and terrifying), who makes him an offer that's too good to be true and too enticing to refuse.

A lean, pared back thriller, "Thief" might be the most authentic heist film on this list. The robberies are treated as another mundane part of Frank's life, and Caan's unshowy, quiet proficiency when it comes to cracking safes is uncannily realistic.

18. Inception

If it wasn't for the head-scratching science fiction elements, Christopher Nolan's enigmatic film would be a fairly standard heist movie. With them, it becomes one of the most enduring heist films of all time. All the tropes are here — the genius mastermind, the recruiting of the crew, the meticulous planning — but instead of stealing something, the gang are planting a thought in the dreams of a businessman played by Cillian Murphy.

Leonardo DiCaprio plays Cobb, the leader who designs dreams and acts as the guide to this convoluted premise; unlike some of his later films, Nolan lays out the rules of this world clearly and comprehensively, so that the audience is never lost. In fact, the only real complication is Marion Cotillard as Cobb's dead wife, who turns up as his subconscious throughout, throwing a spanner in the works. Each member of the crew is brilliantly sketched out, from Joseph Gordon Levitt's matter-of-fact fixer to Tom Hardy as the flamboyant forger. "Inception" is still Nolan's most purely entertaining film, with constantly changing scenery and plot twists that keep the audience guessing right up until the final, famously ambiguous shot.

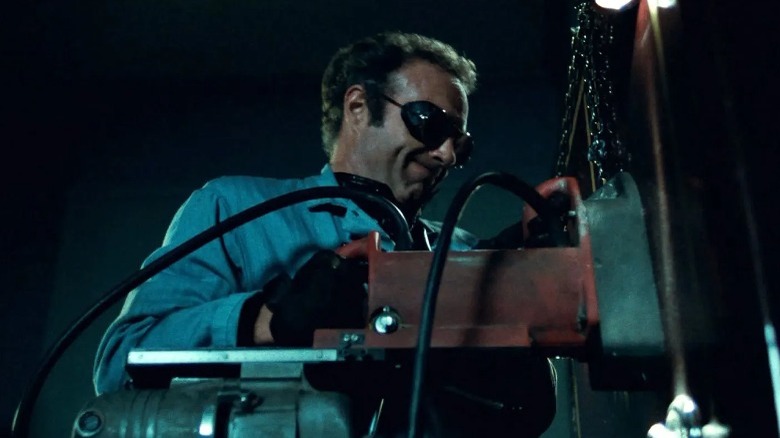

17. The Killing

One of Kubrick's first films, "The Killing" is one of the formative heist films, laying the foundations for pretty much the whole genre. Sterling Hayden's smooth Johnny Clay recruits a desperate group of first-time criminals to assist in his plan to steal two million dollars from a racetrack. The beauty of this film lies in the way Kubrick parses out details of the heist bit by bit, along with the non-linear structure which shows different elements of the heist unravelling simultaneously while a droll narrator lays out the timing of the heist itself.

Of the unlikely group of robbers, the uniquely odd Timothy Carey comes close to stealing the show as the rat-faced sharpshooter, but the always great Elisha Cook Jr., who plays a henpecked cashier who constantly has to placate his calculating wife (Marie Windsor), ends up being the standout. Cook gets the most pathetically triumphant moment of the film, while Windsor is just about the most venal, avaricious character in a movie full of them. Kubrick's stylish cinematography and sense of irony make "The Killing" eminently watchable, and the final scene is one of the most unbearably tense in his filmography, as Clay's plan comes crashing down because of one tiny oversight.

16. Thunderbolt and Lightfoot

A poignant blend of road movie, buddy movie, and heist movie, Michael Cimino's debut follows Clint Eastwood as the legendary Thunderbolt, a bank robber who got put away for an infamous bank robbery and is now on the run from his former accomplices, the brutal Red (George Kennedy) and the dopey Goody (Geoffrey Lewis). He eventually runs into a drifter named Lightfoot (an impossibly young Jeff Bridges), and after the four reconcile, they plan on completing the heist they didn't finish years earlier.

What sets "Thunderbolt and Lightfoot" apart from other heist films is the combination of broad comedy and melancholy that infuses the film. The scenes showing the gang raising funds for the heist are genuinely funny (especially Goody getting a job as an ice cream man) but the ending is one of the saddest of the era. The whole gang is perfectly cast — Eastwood is more human and natural than he'd ever been up to this point, Kennedy is unpredictable as the savagely violent antagonist, Lewis is incredibly sweet, and Bridges manages to make his cocky upstart genuinely endearing. Some of the dialogue is creaky and there's a very '70s misogynistic streak running through the movie, but the bond that forms between the two leads is genuinely touching.

15. Hell or High Water

In a genre that largely deals in black and white, it's refreshing to come across a film in which all of the main characters are likeable and feel like real people. This modern day western adds an interesting little crinkle into the premise — rather than one big robbery, brothers Toby and Tanner (Chris Pine and Ben Foster) commit a series of bank heists on the road, targeting the bank chain that harassed their mother and put her in an early grave. Pursued by an irascible sheriff played by Jeff Bridges and his Mexican partner (Jay Birmingham), the brothers move quickly from bank to bank, burying their getaway cars after each robbery, and laundering the money in Las Vegas to avoid detection.

Pine is almost unrecognizable, giving an understated, measured performance as the brains behind the operation that's very different from his usual cocky on-screen persona, but it's Foster who steals the film as his utterly fearless older brother. A lesser film might have made Tanner unhinged or psychotic, but "Hell or High Water" takes pains to show you how much the brothers care for one another. Despite Tanner's obvious issues, he has a heart and looks out for his younger brother. Often feeling like a heist film directed by the Coen brothers — in the best way possible — "Hell or High Water" is a meditative, wry take with a sting in its tail.

14. Gonin

Another heist movie with a heavy dose of social commentary, "Gonin" (or "The Five") is an old-fashioned story of a mismatched group of misfits coming together to rip off the yakuza. Bandai (Koichi Sato) is a struggling disco owner and heavily in debt. When he encounters several other undesirables in similarly dire straits, he comes up with a plan to rob the gangsters and pay them back with their own loot. Unfortunately, the group he recruits are among the most erratic bunch of amateur thieves in Japan, and the robbery goes off the rails almost immediately.

As they are hunted down by two gay hitmen (one of whom is played by the legendary Takeshi Kitano), the secret lives of the gang are revealed, including one particularly disturbing revelation — they are then picked off one by one until the survivors take the fight back to the yakuza. Stylish, brutal, and completely unforgiving, director Takashi Ishii paints a singularly fatalistic portrait of Japanese society, pulling the rug out from under his audience on numerous occasions. The gang themselves serve as a kind of microcosm of the cracks that were appearing in Japanese society in the '90s, consisting of a pimp, a corrupt cop, a desperate salaryman, and a gigolo. Even the hitmen are outcasts, looked down on by their bosses. "Gonin" is an original and vital piece of modern Japanese cinema, and criminally overlooked in the west.

13. The Silent Partner

A Canadian thriller with a neat premise, "The Silent Partner" follows Miles Cullen (Elliott Gould) an unassuming bank teller who learns that his bank is going to be robbed when he notices a threatening message written on a payslip while he's cleaning up the work floor. The next day, rather than putting his transactions into his till, he deposits the money into a lunchbox under his workstation, so when the bank robber turns up, he only gets a fraction of the money while Gould quietly leaves with the lion's share.

Once the robber (Christopher Plummer) learns he has been cheated, he tracks down Cullen and threatens to kill him unless he gives the money back. So begins a desperate game of cat and mouse as Cullen tries to stay ahead of the thief and the law while the robber is determined to get his money at any cost.

A clever, witty screenplay from Curtis Hanson (the writer-director of "LA Confidential") demonstrates all the different variables and elements that can go wrong in planning a heist. Both characters have their agendas, and neither is depicted as an idiot. They each get the better of the other at various points in the film.

Plummer is wonderfully unhinged as the intense psychopathic bank robber who employs a variety of disguises throughout the film, from Father Christmas to dressing in drag. The film makes great use of his striking blue eyes and makes you wish he'd played a villain more often.

"The Silent Partner" is a brilliant, underseen heist film with an elegant plot, some genuinely unpleasant moments, and a great, satisfying payoff.

12. Killing Them Softly

The first of two heist films on this list based on a book by George V. Higgins, "Killing Them Softly" is a criminally underrated gangster movie with some unhinged performances and a memorably unconventional robbery at its center. The bulk of the film concerns hitman Jackie Cogan (Brad Pitt) as he dispassionately tracks down and eliminates anyone connected to a robbery. The fateful heist itself is the film's launching point, and is beautifully set up and executed. It's based on an inspired premise, too: Years earlier, Markie Trattman (Ray Liotta) ripped off his own poker game, inadvertently making him the perfect patsy when three unlikely robbers plan an almost identical crime.

The prep for the robbery feels incredibly authentic. The two thieves, Frankie (Scoot McNairy) and Russell (Ben Mendelsohn) are in utter shambles. Tasked with providing weapons, gloves, and masks, Russell turns up with stockings, washing gloves, and a shotgun that's so sawed-off that cartridges poke out of the end. They're hardly the smoothest of operators, hysterically bickering like children in the car as they hype themselves up. Still, they prove to be effective criminals, walking out with all the money.

In many ways "Killing Them Softly" feels like a heist film from the classic film noir era, as the thieves get away with the initial crime, but are brought down by their own hubris. In this case, though, it's one character's outright stupidity that serves as their undoing.

11. The Hot Rock

A lesser known entry, "The Hot Rock" is one of screenwriter William Goldman's wittiest and most playful screenplays, and one of the most outright funny heist movies of all time. Based on the Donald E. Westlake story, but much more lighthearted in tone than it's source material, "The Hot Rock" technically consists of four heists — its hapless band of criminals attempts to steal the same diamond from a museum, a prison, a police station, and, finally, a bank. As their patron (Moses Gunn) says, "I've heard of the habitual criminal, but I never thought I'd be involved in the habitual crime."

Robert Redford, George Segal, Ron Liebman, and Paul Sand make a brilliantly funny team, constantly bickering and irritating each other. Segal is at his neurotic best as the lock picker, go-between, and grifter (the moment when he freaks out while picking a museum lock is hysterical). Liebman is a blast as the single-minded getaway driver, and Sand's ineffectual explosives expert is so well observed that it's a wonder that he didn't go on to greater things. Redford is the glue that holds the whole film together, though, largely playing it straight but allowing himself a moment of levity in the film's final moments, which is one of the most well-earned feel-good endings to a heist film ever. Shamefully underseen, "The Hot Rock" deserves way more exposure.

10. Odds Against Tomorrow

While "Touch Of Evil" is often held up as the final flourish of the classic film noir era, "Odds Against Tomorrow," released a year later, is noir through and through — and an excellent heist movie to boot. Like "Dead Presidents" it spends the majority of its runtime familiarizing the audience with the main players: the smooth but struggling jazz musician Harry Belafonte, hugely in debt to a local gangster, and the bitter racist Robert Ryan, emasculated by his wife and desperately trying to regain some form of independence. They loathe each other on sight, and Ed Begley's genial ringleader has his hands full trying to keep them from killing each other before the robbery even begins.

The plan itself is beautifully simple but ultimately undone by dumb luck. It's almost over before it even begins, with the hostilities between Belafonte and Ryan boiling over right from the start. Everyone is firing on all cylinders here, giving muscular, raw performances, but Ryan in particular is just incredible, managing to elicit pity, if not outright sympathy. As loathsome as he gets, you get the impression that he hates himself even more than everyone else does. The ending rivals "White Heat" in its incendiary nature, ensuring the film noir age went out with a bang. That final line is a heck of a punchline, too.

9. The Friends of Eddie Coyle

"The Friends Of Eddie Coyle" is our second Peter Yates film in a row, but tonally it's completely different from "The Hot Rock." While "The Hot Rock" is a fun, laidback romp, "The Friends Of Eddie Coyle" is one of the most pessimistic, bleak crime stories ever committed to film — even the title is ironic.

An adaptation of a George V. Higgins novel, "The Friends of Eddie Coyle" follows the titular protagonist (Robert Mitchum) as he struggles to get out of jail by snitching on his fellow thieves after a series of bank robberies. Yates goes to great lengths to show how the grift never ends on either side of the law; we see informants and cops lie and cheat just as much as the thieves. "The Friends of Eddie Coyle" is memorable for the innovative, albeit ruthless, methods employed by the bank robbers — rather than using any high tech gadgets or heavy duty firearms, they simply hold the bank manager's family hostage.

"The Friends of Eddie Coyle" cast a huge shadow over the crime cinema to come, especially modern classics like "The Town" and "Killing Them Softly," which lift plot elements from this movie wholesale. Yates might not be the most celebrated film director, but his two entries on this list demonstrate his versatility. This is his crowning achievement: an unapologetically downbeat, gritty neo-noir that gave Mitchum his last truly iconic role, and that features excellent supporting turns from Richard Jordan and Peter Boyle.

8. Heat

Michael Mann's seminal film is one of the most influential crime thrillers ever made, and its fingerprints evident on films as varied as "The Dark Knight" and "Infernal Affairs." Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, in their first appearance on screen together (if we ignore "The Godfather Part Two," in which they never shared the screen), give electric performances as the consummate professional thief and the formidable detective on his tail.

It's a simple story told on an epic scale, and Mann withholds judgment on his characters, letting the audience decide who to empathize with. Pacino's workaholic detective is on the right side of the law but ignores his wife, while De Niro's callous thief begins a sweet relationship with the girl he meets in a coffee shop. Pacino and De Niro play a game of cat and mouse that lasts the whole film, culminating in the central heist scene and subsequent shoot-out. The thieves (De Niro, Val Kilmer, and Tom Sizemore) move like a military unit, hotly pursued by Pacino and his team.

Mann used the actual gunshots recorded on set rather than sound effects to create more immersive scenes, and it works — the showdown in the middle of the city is one of the most kinetic, exhilarating shootouts in film history. An elegiac, impossibly cool film, "Heat" has had an immeasurable impact on modern cinema.

7. Reservoir Dogs

Despite having a reputation as one of the most iconic heist movies of all time, Quentin Tarantino's debut film doesn't even show you the heist itself, instead focusing on the gang's preparations and the chaotic aftermath. Whether he acknowledges it or not, Tarantino borrowed much of the story from Ringo Lam's "City On Fire," but there's little doubt that this is a superior film — the dialogue crackles right from the pre-titles scene, and Tarantino conveys the chaos of the bank robbery without ever showing the characters stepping into the bank.

As with the best heist films, the cracks start to show after the robbery itself, and while the dialogue, pop culture references, and infamous torture scene are rightly celebrated, what often goes unmentioned is Tarantino's incredibly mature storytelling ability — the non-linear narrative structure and his smart use of flashbacks reveal each of the robbers background, and informs their characters in the present without requiring too much exposition. Hugely influential, "Reservoir Dogs" is still Tarantino's leanest, most muscular film.

6. Le Cercle Rouge

Jean Pierre Melville's slick style was uniquely suited for a heist film. He previously made "Bob Le Flambeur," another classic, but "Le Cercle Rouge" is more satisfying on every level. Melville missed out on his chance to direct the ultimate heist film when he was turned down for "Rififi", but got his second chance with this effortlessly cool and very French movie.

"Le Cercle Rouge" features the always fantastic Alain Delon as a newly released felon who immediately begins planning a jewel robbery, recruiting fugitive Gian Maria Volonte and alcoholic ex-cop Yves Montand to assist him, all the while being pursued by dogged detective Andre Bourvil. The 20-minute heist sequence is almost as great as that in "Rififi," again conducted in complete silence, and with Melville's typical flourish. And, as ever, while the heist itself goes down without a hitch, it's the pre-existing grudges that prove to be the gang's undoing. Honor among thieves and loyalty are big themes, but any preconceptions audiences might have about the mythic romantic criminal are thoroughly washed away after the abrupt and incredibly fatalistic ending.

5. The Ladykillers

The interesting thing about heist movies is that the heist itself can just as easily serve as a catalyst for comedy. "The Ladykillers" is a perfect example. Alec Guinness' comically sinister professor plans a bank robbery in the house of the elderly Mrs. Wilberforce (Katie Johnson), and uses her as an unwitting courier for the money. The robbery goes off without a hitch, but when she discovers what's up, the gang has to get rid of her.

This premise could easily be a lot darker, but in the hands of Alexander Mackendrick it becomes a morbidly funny comic masterpiece, as the gang decide that it's infinitely preferable to bump each other off than to murder an elderly woman. The whole gang is brilliantly cast (Peter Sellers and Herbert Lom being the standouts), with each of their personality flaws evident from very early on. Lom's humorless gangster in particular harkens back to classic Hollywood heist films, as the professional hood "can't stand" little old ladies.

In fact, a huge amount of the film's success comes from characters playing it straight amidst the increasingly absurd situation they find themselves in. This applies to the central heist as well. "The Ladykillers" proves that you can build a great comedy around a well-planned heist — the robbery itself is genuinely compelling and only falls apart because of the human element, just as in the films from the classic Hollywood era.

4. Dog Day Afternoon

In contrast to the slick, masterfully-planned heists you usually see in the movies, "Dog Day Afternoon" reminds us that bank robberies are usually a terrible idea.

The masterstroke of Sidney Lumet's seminal film is how finely the director balances comedy and tragedy. Lumet really makes us feel for bank robbers Sonny (Al Pacino) and Sal (John Cazale, in his finest film role), but with one accomplice pulling out immediately and the cops getting wind of the robbery before they can enjoy the fruits of their labor, their woefully under-prepared heist is doomed before it can even begin.

Sonny and Sal's inexperience makes them both humane and volatile. Sonny isn't your standard bank robber; he's not motivated by greed, but rather plans on using the proceeds from the robbery to pay for gender-reassignment surgery for his lover (Chris Sarandon). As such, he quickly endears himself to both his captives and New York's general public, and his repeated refrain of "Attica! Attica!" — a reference to the infamous New York prison uprising — neatly positions him as one of us, not just a desperate criminal. It's easy to root for someone who fights back against an oppressive system.

Similarly, despite his assurance that he's ready to kill all the hostages, Cazale makes Sal the most tragic character in the film. He's hopelessly simple (when asked which country he wants to escape to, he names Wyoming) and Calaze's performance carries a great sense of melancholy. More than anything else, it's a terribly sad film, with a creeping sense of dread as it nears its grimly inevitable conclusion.

3. Criss Cross

One of the most underrated film noirs of all time, Robert Siodmak's "Criss Cross" has Burt Lancaster as his usual, perpetually doomed self, playing the disillusioned hero who takes a job as a driver for an armored car company when his femme fatale ex Yvonne DeCarlo walks back into his life. The best thing about "Criss Cross" isn't the heist itself (even though the gas masks and smoke bombs make for some great visuals), but the story leading up to it — the only reason that Lancaster even pitches the plan is to explain his presence in DeCarlo's home to her gangster husband Dan Duryea.

The robbery isn't just incidental, though, as we see a distinguished heist planner (Alan Napier) meticulously plotting the robbery down to the last detail. The most suspenseful scene in the film is the one immediately following the heist, as Lancaster is recovering in hospital and is visited by several people, one of whom may or may not be a hitman. "Criss Cross" is a fatalistic, often elegiac walk into the dark side; Lancaster has so many opportunities to go straight, but his descent back into his old ways is grimly inevitable. Dan Duryea is brilliantly slimy as the gang's ringleader, and DeCarlo makes for an oddly sympathetic femme fatale. The ending is both tragic and poetic — it's pretty much the perfect film noir.

2. Rififi

The quintessential heist film, the masterstroke of Jules Dassin's "Rififi" is that the robbery itself goes off without a hitch, only for problems to arise after the fact. The gang are all portrayed as seasoned professionals, and the heist is one of the most iconic sequences in cinema, shot in real time (taking about 30 minutes) and executed in complete silence — there's no dialogue and no music. It's a supremely tense scene, and features an incredible attention to detail; the robbers wear ballet shoes to muffle the sound, and use an umbrella to catch the debris as they knock through the ceiling.

Dassin makes the four gang members likeable and charismatic, but imbues each one with a weakness that's exploited by the gangsters pursuing them. As the thieves' ringleader, Jean Servais has a wonderfully craggy face, mournful eyes, and a laconic delivery ideally suited for film noir, while Dassin himself plays the lovelorn safecracker who provides much of the film's pathos, and whose romantic tendencies land everyone in hot water.

1. The Asphalt Jungle

Once called the greatest film ever made by Jean Pierre Melville, there's no denying the impact John Huston's film noir made on cinema. It features all the archetypes associated with heist films, from Doc (Sam Jaffe) as the mastermind with a weakness for pretty girls to the Sterling Hayden's Dix, a heavy with hidden depths. Featuring the iconic line that describes crime as "just a left-handed form of human endeavor," "Asphalt Jungle" is the definitive heist film, and a clear influence on "Reservoir Dogs," among many others.

A formidable rogues gallery is played to perfection by a superb cast; there's the corrupt lawyer (Louis Calhern) who wants to bankroll the robbery despite having no money of his own, the pitiful bookie (Marc Lawrence), the genial hunchbacked getaway driver (James Whitmore), and slick safecracker Louis (Anthony Caruso), not to mention a young Marilyn Monroe in one of her first film roles.

The necessities of the Hays production code meant that the robbers had to either go to prison or get killed before the end of the film. However Huston takes pains to portray the law enforcement as either puritanical or corrupt, while the thieves themselves are all much more sympathetic; one of the "villains" doggedly searches for his family farm out of a childish sense of nostalgia, even as the net tightens around him. Pulpy, bitterly ironic, and heartbreaking in equal measure, "Asphalt Jungle" might just be the greatest heist film of all time.