Why The World Of 'Cars' Is So Maddening (And Out Of Step With Pixar's Best Work)

(Welcome to The Soapbox, the space where we get loud, feisty, and opinionated about something that makes us very happy...or fills us with indescribable rage. In this edition: why the world of Pixar's Cars series, and the fan theories it inspires, are so frustrating.)

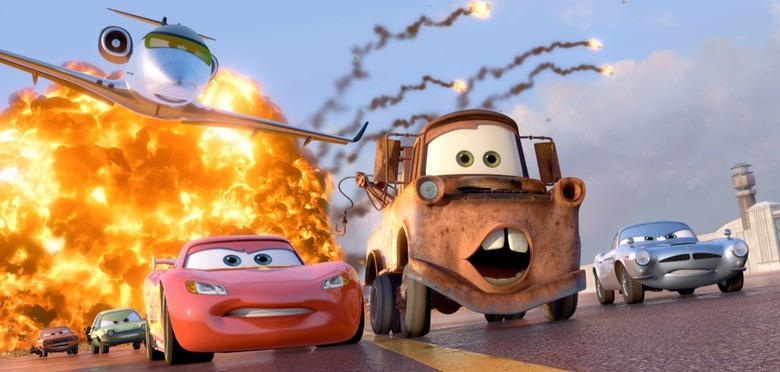

With a new Cars movie racing into theaters this week (Do you get it? "Racing"? Because Lightning McQueen is a race car; it's funny because he races, just like the movie is racing into theaters), it's time once again to revive that dormant question that has persisted for just over a decade. How exactly does the so-called "world of Cars" work? There are few answers within the movies themselves, so a few ideas have sprung up online. Have the cars adopted the personalities of their last human drivers? Did sentient cars take over the world, sending humans off on a massive intergalactic cruise ship for centuries? Did humans literally turn into cars? These theories have all gained a level of traction (Do you get it? Traction! I made another car-based pun!), while also remaining utterly ridiculous.

To be fair, I have previously written about my distaste for cinematic fan theories, few of which are more well-known than the Pixar Theory. But today, I come not to bury the Pixar Theory, or any of those other Cars-related theories; I come to empathize with them. I do genuinely think that each of the theories mentioned in the previous paragraph are utterly silly, and that a glut of such theorizing can do great harm to film discourse at large. But specific to the fan theories zooming around Cars ("Zooming"! I made another pun!), which will inevitably kick up again after Cars 3 opens this Friday, there's a big question worth exploring: why do people feel the urge to crack the code of whatever's going on in the Cars movies? While some other big mainstream films can inspire fan theories, such as Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy, why is it that the Cars movies have led to all manner of conspiracy-style ideas?

Theorizing Can Be Okay

When someone tries to explain the deeper meaning of a film, such as David Lynch's Mulholland Dr., it may be infuriating. (Lynch is one of our best filmmakers, in part because he has so little interest in explaining anything.) However, a Lynch-derived fan theory makes a certain amount of sense. Mulholland Dr. is a fabulous, terrifying mystery, so searching for some clues, some greater meaning, is almost a natural response precisely because there are so few answers directly provided in the film.

But...Cars? Say what you will about these films, but they are not great mysteries, nor are they designed to be. The first Cars is a laid-back, overly slow-paced and sometimes pleasant hang-out movie, where Lightning McQueen, the lead character, learns that, to appreciate his life and not take things for granted, he should get out of the fast lane and move one mile at a time. (More car-based jokes! One more, and I get a free sub.) The 2011 sequel Cars 2, a big qualitative step down from its predecessor, is a throwback to' 60s-era spy thrillers, but its central mystery involving alternative fuels is solved clearly and quickly. The fan theories springing up around Cars have next to nothing to do with the plots or characters of these films; they nip at the core question that remains unanswered, which is how literally anything in these movies can exist.

This is Not a Normal Pixar Problem

Why do the cars in the Cars movies have handles on their doors? Why, you might ask, do they have doors? Seeing as there are no humans in this universe, or other live creatures, there would be no one to use the car doors. Right? Hell, leave aside why the cars have doors or handles: how do they have doors or handles? How did the roads on which the cars drive get built? Or the towns? Or the restaurants, or the gas stations, and so on and so on. The fan theories I cited at the top exist because there have been so few, if any, answers extended to these questions. Few other Pixar films remain so baffling in their world-building.

There may not be massive exposition dumps in The Incredibles to clarify how the main characters have superpowers, or a lengthy dissertation as to why a rat could even approach cooking a decent stew in Ratatouille, or how, in Up, an elderly man who needs help walking up or down a flight of stairs could inflate countless balloons in one night so that his house turns into a makeshift flying machine. There's a simple reason why no such expository dialogue exists in those films, or throughout the majority of Pixar's filmography: all you need to enjoy these movies is the appropriate suspension of disbelief. The Incredibles wasn't even the first film in 2004 to feature superheroes. Ratatouille, for its fanciful premise, squarely took place in the real world. (Don't forget how quickly everyone else in the restaurant leaves once the gawky human Alfredo Linguine reveals that there's been a rat literally pulling the strings underneath his toque from the start.) And Up may have whimsical flourishes, but it still allows for necessary touches of reality, from a bloodied forehead to Carl Fredricksen's house falling apart as the balloons start to pop after wear and tear. Cars does not have the same luxury of suspension of disbelief, nor is it interested in said luxury.

It's About Cars

Indulge me for a second. In the early 1980s, the stage show Cats was a smash hit on London's West End. Naturally, its creators, Andrew Lloyd Webber and Trevor Nunn, wanted to transfer the show and replicate its success on Broadway. In doing so, they reached out to Harold Prince, the legendary theatrical producer and director, and pitched him the show, a two-hour, sung-through opus where anthropomorphized cats sing, dance, and prance around before one of them is chosen to ascend to the Heaviside Layer (the show's version of Heaven). Prince, after hearing the pitch, asked if he was missing some sort of allegorical or metaphorical explanation about the show, perhaps a connection to the British royal family or the country's class system. Webber, after pausing, said "Hal. It's about cats."

I cannot know the inner workings of the mind of John Lasseter, the genius who helped bring Pixar into being and who directed the first Cars as well as classics like Toy Story. I can only guess as to what fascinates him so much about cars that it led him to making a film dedicated to the open road of Route 66 and the presumed beauty of automotive mechanics. (I imagine that gearheads in general might be more understanding or forgiving than I am.) Maybe he reads theories like the ones cited above, and he smiles knowingly, silently appreciating that some hard-thinking fans out there have figured out what's really going on in the Cars movies. But I have a feeling that, if pressed, he'd essentially say, "It's about cars."

Recently, Matt Singer of ScreenCrush (in the first link in the opening paragraph) went as close to the source as possible, asking Pixar creative director Jay Ward, who wrote the internal document "The World of Cars Owner's Manual," where the cars came from. Ward suggested that "cars adopting human personalities" idea, while clarifying that it's his idea, not something in the series canon officially. In 2011, with the release of Cars 2, Todd Gilchrist of Box Office Magazine sat down with Lasseter himself and asked him about the mythology of the universe, inspired by that film's references to dinosaurs (as well as the original's comparison of cow-tipping to tractor-tipping). Regarding dinosaurs, Lasseter said the following: "...the dinosaur thing is just a funny line. We figure that if someone really wants to see it, we can figure out what a dinosaur in this world was or looks like."

So, in short...it's about cars.

A Frustrating Mystery

On one hand, this is not automatically a bad thing. I honestly don't know that these films (or the Planes spin-off series; remember those?) would be improved if they were secretly about how mankind was subsumed into the vehicles they drive, or if any of the other theories were validated. They might make sense, but making sense isn't the same thing as telling a satisfying story. The Cars movies don't need to have a grand message, a greater theme in the way that the Toy Story films and Inside Out and Finding Nemo are about parenthood, or how WALL-E is about humanity, or how Up is about accepting the loss of a spouse or loved one. Pixar's films can be entertaining without some deeper metaphorical element.

The problem isn't that the Cars movies don't have big-scale messages; it's that they don't seem to display a level of interest in the world they depict outside of surface-level gags straight out of The Flintstones. There are jokes aplenty in these films, all based on vagaries of the human world, but with cars instead. The gags range from celebrity cameos – Bob Cutlass and Jay Limo instead of Bob Costas and Jay Leno – to personality types. A squabbling husband and wife on a road trip are visualized as dual minivans, because of course they are; even the tractor-tipping joke in the first movie is cute, but just shifting personality traits from point A to point B. These jokes may inspire chuckles, or they may have inspired chuckles originally. (In 2006, it was probably a bit wittier to cast Jeremy Piven as Lightning's fast-talking agent than it is when you watch the film in 2017.) Because the first two films seem unwilling to engage in even a whiff of emotional profundity, they remain surface-level. The early reviews for Cars 3 imply that this film will rely more on emotion than the others, so maybe, hopefully, things will change. We haven't gotten any answers about the meaning of the world of Cars, because there are almost certainly no answers to be had.

It certainly doesn't help that the writers have gone on record to say that they deliberately do not think about these questions.

In lieu of answers provided by the filmmakers, we make them up ourselves. Again, the theories I linked to in the first paragraph of this essay are, in my opinion, extraordinarily goofy. But at least they're trying to explain what the hell's going on in these movies. (I have larger issues with the overall Pixar Theory, but we can table that discussion.) Barring a shockingly unforeseen circumstance, Cars 3 is not going to pull back the wool over our eyes and tell us what's really going on here, sheeple. In other Pixar films, the lack of a great mystery wouldn't be a problem; in the Cars movies, the problem is that the entire world is itself a great mystery, despite its creators essentially shrugging. Maybe Cars 3 will surprise me (I hope it does), but it would be hard to imagine a satisfactory conclusion provided 11 years after the first film, by right of its very existence, asked without answering the question at the core of these fan theories.