Reflections On Where The Wild Things Are – The Trials, Wonders, And Joys Of Childhood

Note: The following will contain minor spoilers for the movie Where The Wild Things Are and will assume that you know the plot of the book it's based on.

Let's get this out of the way: Where The Wild Things Are is not a film for everyone. While Warner Bros. might hope to position this as a kids' film, it lacks many of the trappings you might expect from the genre; Max doesn't go on some grand quest with the Wild Things and, just like the book, not that much changes in the real world by the time you reach the end of the story. Even the aesthetic of the world, laden with its warm yet monochromatic look, doesn't lend itself to conventional notions of whimsy. But what the film lacks in convention, it makes up for faithfully capturing many elements of the childhood experience, complete with its resplendent wonder as well as its crushing disappointments.

As the film opens, we get a few glimpses of Max's (Max Records) life. His sister (Pepita Emmerichs) is more focused on her older friends than on him, while his single mother (Catherine Keener) struggles with her job. Meanwhile, all Max wants is someone to play with. One night when his mom is enjoying a glass of wine with another man in their living room, Max has an altercation with her, flees his house, runs off into the woods, and escapes into the magical world of the Wild Things. The Wild Things collectively decide to make Max their king. And while the wild rumpus does begin forthwith, these Wild Things (unlike the Wild Things in the book) believe that Max, as their king, will help to take away their pain and loneliness.

As we already know, adapting the book was a Herculean task on the part of director Spike Jonze, who struggled for many years to push it through the studio system. But even setting aside the filmmaking and business aspects of the film, the artistic challenges must have also been formidable. Sendak's seminal children's book, Where The Wild Things Are is only ten sentences long and is light on story, to say the least. What I love about what Jonze and screenwriter David Eggers have done is that they've made the Wild Things extensions of Max's inner psyche. These tall, enormous creatures represent a heightened version of Max's fears, desires, and dreams. While the Wild Things are capable of having fun and joking around, their condition is equally tragic in their capacity for pain, and chilling in their potential for destruction. Moreover, the meandering storyline mimics a child's style of imaginative play. I would argue that no other film this year paints a more profound or true-to-life picture of what it's actually like to be a kid.

The film becomes a story of self-discovery, and about Max's realization that he can cause pain, that he possesses the power to hurt those he cares about, even in their hour of deepest need. At the same time, it's about Max coming to grips with the reality of his situation. A profound sense of loneliness pervades the proceedings, both for Max and the Wild Things. How does one cope when the friends one has counted on, when the relationships one has known and trusted have forsaken us? This is the struggle that Max and Carol (James Gandolfini), one of the head Wild Things, are forced to contend with.

The world of the Wild Things, while not laden with bright and fancy colors, is nonetheless stunningly gorgeous. It is a land of beautiful sunsets, windswept beaches, and endless sand dunes, a world where any child would be happy to spend some time in. And the Wild Things themselves are wonders to behold. On a technical level, Jonze in conjunction with Jim Henson's Creature Shop, have created characters that fuse CGI and practical effects so successfully, they deserve to join the pantheon of superlative entries in the category. The Wild Things bound effortlessly across their kingdom, smashing and interacting with the environment so frequently that you often forget that these creatures don't actually exist in the real life. But they also emote with facial movements and with eyes that sometimes seem as expressive as those of humans. While hearing human voices come out of the mouths of the mouths of these things might take some getting used to, the performances are uniformly excellent, especially that of Lauren Ambrose, who plays a gentle Wild Thing named KW.

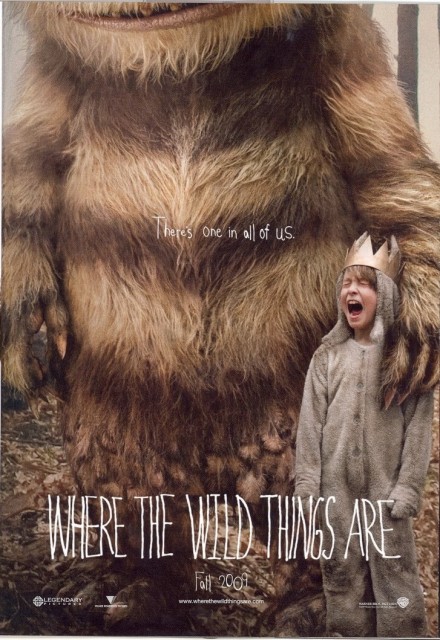

There are also some dark and troubling moments in the film; the mature themes left several kids in my screening crying by the end. I remember seeing the poster for the movie, which shows Max screaming, and a tagline proclaiming "There's one in all of us":

I thought to myself that that line probably referred to the idea that there's a creative and imaginative kid inside each one of us, one who could easily dream up the complete and detailed world of the Wild Things in his head. But what I've come to realize is that the movie is saying there's a child in all of us, complete with all the joy, imagination, petulance, sadness, and pain that that implies. Carol struggles throughout the whole movie to come to grips with his changing environment, latching onto anything that will keep things status quo; that's part of the reason why he helps make Max their king in the first place. In fact, the inner turmoil in Carol mirrors that part deep within us, that stubborn part that threatens to lead to our own undoing. It is the stubbornness of not being able to accept things as they are, of not being able to accept change. What the movie is trying to say is that perhaps by letting go, we can, each of us, find some kind of peace.