Guillermo Del Toro's Gothic Horror Masterpiece Cronos Has A Sequel You Had No Idea Existed

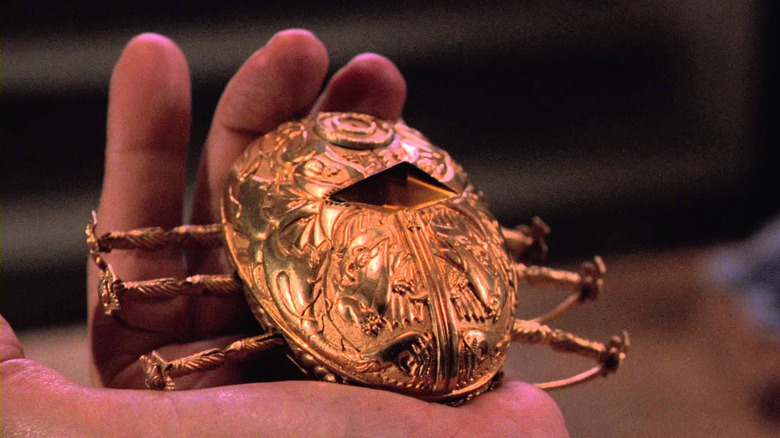

Guillermo del Toro intimately understands monsters. This fascination goes beyond skin-deep appreciation, as monstrosity in del Toro's oeuvre is an acquired trait as opposed to a compulsive instinct. For instance, the Creature in del Toro's "Frankenstein" is a sympathetic victim who chooses to end the vicious cycle of abuse and preserve his innate tenderness in spite of the horrors. This instinct to humanise what we traditionally deem as monstrous can be traced back to his 1993 debut feature "Cronos," which reimagines the vampire mythos by giving it an extraordinarily stylish tint. While this debut isn't as thematically rich or layered as "Pan's Labyrinth" or "The Devil's Backbone," it showcases an emotional depth (and a deep love for the macabre) that blooms beautifully throughout the director's singular career.

"Cronos" is somewhat overlooked in comparison to del Toro's later works, which might be attributed to its extremely limited U.S. release, where it played at a total of 28 screens. What's more, being an indie feature debut that was mostly in Spanish, "Cronos" wasn't as eagerly sought out by mainstream theater-going audiences at the time. Today, it is considered a genre classic, a fresh, inventive tale about humanity eventually prevailing over monstrosity, even after the latter pushes us into the depths of addictive depravity.

As it turns out, "Cronos" seems to have a standalone sequel titled "We Are What We Are" that no one ever talks about. This makes sense, as its only link to del Toro's film is extremely flimsy in the form of Daniel Giménez Cacho's Tito, who reprises his "Cronos" role in this Jorge Michel Grau film. But does Grau's film examine horror in a novel way, and does it have anything interesting to say?

The Cronos sequel indulges in bleakness that might be tough to stomach

While Cronos uses the fantastical to expose the monstrosity inherent in the human experience, it ends with a decisive final act that feels humane and hopeful. In contrast, "We Are What We Are" doesn't entertain any silver linings, as it paints a relentlessly macabre picture of a family crumbling after the death of the patriarch. No, this isn't a film about grief and what it does to us, but an uncompromising look at a dysfunctional family dynamic that already hides a nefarious secret. There are no literal monsters or ghosts here, as existence itself is a horrifying ordeal in a city overrun with corruption, which widens the gap between the ones that drown in riches and those who have to fight for scraps.

Grau knows how to weave anxiety into a story that keeps taking dark turns, and there is clearly a sincere attempt to tackle genre tropes from a subversive perspective. For the most part, it works, as the film asks pertinent questions about the nature of guilt and shame, and how they might manifest as unforgivable acts. Is the family's monstrosity an extreme reaction to their socioeconomic circumstances, or is it merely a symptom of moral bankruptcy that seeped in through their patriarch? These intellectual strains, although admirable, are overshadowed by the grimness of a film that refuses to take a breather or rein in its unchecked cynicism.

You can also check out Jim Mickle's eponymous American remake of Grau's horror film if you're so inclined (Mickle insists that it's less of a remake and more of a companion piece). This entry is also quite thematically sharp and grisly, but takes a more simplified approach to Grau's depressing original.