This Underrated Sean Connery War Movie Wouldn't Have Happened Without James Bond

Sean Connery famously emerged from relative obscurity to win the part of James Bond over the likes of Cary Grant and David Niven. The producers were certainly rewarded for their faith in the Scotsman, who made the role his own in five hit 007 adventures before walking away (only to return in "Diamonds Are Forever" and "Never Say Never Again.") Those films made him a household name, a sex symbol, and an international icon, but they arguably overshadowed the rest of his career. But he did have significant ability beyond looking great in a tuxedo, and two of his most substantial roles came working with Sidney Lumet in "The Hill" and "The Offence." Ironically, the first of these movies might not have happened without Connery's stint on Her Majesty's secret service.

Although Connery had already started to weary of playing Bond after "Dr. No" and "Goldfinger," he had used his credit from those movies to branch out into more serious dramatic roles, appearing in Alfred Hitchcock's "Marnie" and Basil Dearden's "Woman of Straw." Better still was Lumet's "The Hill," which Connery admitted might not exist without his box-office pulling power after playing the suave secret agent. He told Playboy magazine:

"[The success of Bond] had everything to do with it, of course. As a matter of fact, it might not have been made at all except for Bond. It's a marvellous movie with lots of good actors in it, but it's the sort of film that might have been considered a non-commercial art-house property without my name on it. This gave the producers financial freedom, a rein to make it. Thanks to Bond, I find myself now in a bracket with just a few other actors and actresses who, if they put their names to a contract, it means the finances will come in."

Connery's two films with Lumet are perhaps underrated because they're both pretty bleak and hard-hitting pictures. I'd argue Connery's finest performance came in 1973's "The Offence", where he played a burnt-out copper on the case of a suspected sex offender (Ian Bannen in a BAFTA-nominated role) who may harbor deviant fantasies of his own. Eight years earlier, he was almost as good in "The Hill," playing a sardonic military prisoner who clashes with the authorities after the needless death of a fellow inmate. Let's take a closer look.

What happens in The Hill?

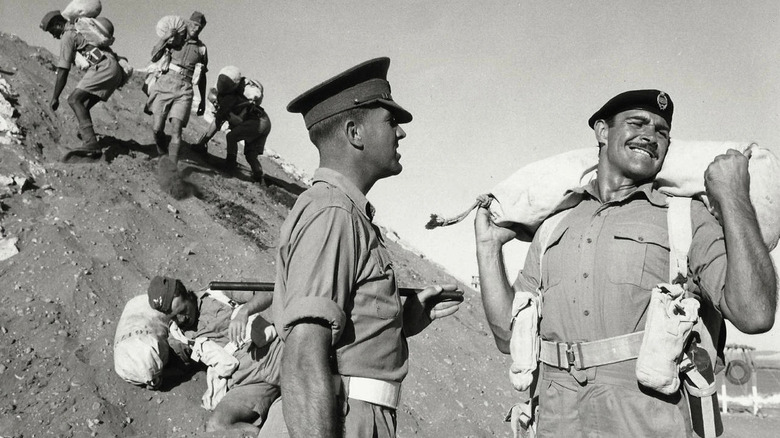

"The Hill" is a powerful drama set during World War II in a British military prison in the baking desert of Libya. The facility is run by hard-nosed Sergeant Major Wilson (Harry Andrews), a seasoned career man who prides himself in his ability to break down reprobates and build them up into worthy soldiers again. His two immediate subordinates are Staff officious Sergeant Williams (Ian Hendry) and kindly Staff Sergeant Harris (Ian Bannen), two men who differ greatly in their approach to dealing with the prisoners. This becomes very apparent when they receive a new batch of inmates: Meek deserter George Stevens (Alfred Lynch), lazy black marketeer Monty Bartlett (Roy Kinnear), hardened drinker Jock McGrath (Jack Watson), and laid-back West Indian private Jacko King (Ossie Davis). Among them is the nut Wilson really wants to crack, Joe Roberts (Connery), a former squadron leader who is convicted for beating up his commanding officer after refusing orders to embark on a suicide mission.

Once the new arrivals are declared fit by the prison Medical Officer (Michael Redgrave), they are handed over to Williams for a harsh introduction to life at the camp. The favored method of discipline is quick-marching prisoners over the hill of the title, a dauntingly steep man-made mound of loose sand. Williams senses Stevens' weakness and targets him for extra punishment, causing him to die from extreme physical and mental exhaustion. The death brings the prison to the brink of riot and causes friction between the head screws while Roberts bravely steps forward to accuse Williams of murder. But who else will have the courage to back him up, and who is going to listen?

"The Hill" was penned by Ray Rigby, a British screenwriter who had served in North Africa during the war and spent two spells in military prison himself. He channeled his experiences into the script, which thrums with unforgiving authenticity. Sidney Lumet's documentary-style approach also adds to the realism, filming on location in an old fort in southern Spain and often employing handheld camera to provide a sense of motion and immediacy. Oswald Morris's lucid cinematography really captures the blazing heat out there on the hill; I can't think of another black-and-white movie that looks this hot. The perspiration on the actors was all real, however, as temperatures during the shoot soared to 46 degrees celsius (that's 114.8 degrees fahrenheit, for reference).

Sean Connery plays part of an excellent ensemble in The Hill

Despite winning awards in later life (most notably his only Oscar for his performance in "The Untouchables"), the general consensus seems to be that Sean Connery was a better superstar than he was an actor. His performance in "The Hill" proves that he was very serious about the latter; not only is he very good the role of the anti-authoritarian Roberts, he also shows what a humble team player he could be. Although the film was built on the back of the enormous success of his James Bond adventures and he received top billing, he very much plays part of an ensemble here, delivering an intelligent and watchful performance that works in perfect sync with the cast of superb character actors.

Indeed, Connery seems happy to lend support to those in far showier roles, such as Ian Hendry as the malicious and cowardly Staff Sergeant Williams and Harry Andrews as Sergeant Major Wilson, who received a BAFTA nomination for his domineering performance. Taken together, these two characters provide a fascinating critique of authority in pressure-cooker circumstances. Williams is an ambitious jobsworth whose self-importance is overblown to dangerous levels by the responsibility he is given, while Wilson is blinded by his devotion to King and Country before Stevens' death presses him into oppressive damage limitation mode. The rest of the cast all have outstanding moments, too, particularly Ossie Davis and Michael Redgrave, before Connery gets a chance to do a little grandstanding towards the end.

Confined almost entirely within the fortress walls, "The Hill" is a gripping and unrelenting film. More of a prison drama than an out-and-out war movie, it perhaps has most in common with Sidney Lumet's "12 Angry Men," which also focused on a courageous dissenter on a mission for justice among a tremendous all-male cast. I'm also reminded of Brian Forbes' similarly underrated "King Rat" (also released in 1965) and its exploration of power dynamics and social structures inside a P.O.W camp. Lastly, the relentless barking authority and moments of black humor recall the boot camp segment of "Full Metal Jacket," without the second-half battle sequence to alleviate the pressure. It's not always an easy watch, but "The Hill" stands comfortably alongside all three as a nailed-on classic with Connery in the middle, just relishing a chance to act. For that, we have to thank James Bond.