Why David Lynch's Twin Peaks Was Canceled

Deep into the second season of "Twin Peaks," the groundbreaking TV series created by David Lynch and Mark Frost, the twisted Windom Earle (Kenneth Welsh) holds Major Garland Briggs (Don Davis) hostage, torturing him for more information on the mysterious and mystical Black Lodge. When Earle asks a drugged Briggs about what he fears most in the world, the warm-hearted soldier responds, "The possibility that love is not enough." It's a statement which, like so much in Lynch's work and in the show itself, has enormous resonance and weight. In particular, the sentiment refers not just to one of the major themes of the series but also to the real-world fate of the show itself.

When the episode containing that scene aired in early 1991, the reception of "Twin Peaks" as one of the most popular and exciting new shows to air on network television had shifted, with not only pop culture in general but its own die-hard fans feeling like something had gone missing. In truth, some key things had gone missing — Lynch, for one, who had taken a break from the series after the sixth episode of the second season and didn't return until the season finale, and Frost, who similarly took a hiatus between episodes 8 and 18. Yet an even bigger loss than the show's two key figures was its most important element: the mystery of the murder of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee). Once that revelation occurred, it left the series and its creators feeling adrift, and though many new characters and plotlines were thrown at the proverbial wall, nothing stuck, at least not in time.

To be fair, the reasons for the cancellation of "Twin Peaks" were myriad and they worked in concert with each other. In other words, there was no single, overarching reason why the show lost its footing and couldn't find it again before the axe came down. Yet, if one had to pick a single blow that caused the show's entire edifice to topple, it was the end of the series' core mystery of who killed Laura, and this injury allegedly came courtesy of the then-president of ABC Entertainment: Bob Iger, who is now the CEO of Disney.

The revelation of Laura's killer was the biggest weakness within Lynch and Frost's collaboration

As the story goes, Iger and the other executives in charge of ABC, which initially aired "Twin Peaks" until its cancellation, put pressure on Lynch and Frost to reveal Laura's killer as soon as possible in the hopes it would allow them to continue capitalizing on the series' first season ballyhoo-like pop culture buzz. Iger has denied that he directly interfered with the show and claimed the reveal was part of a natural artistic process, which may or may not be true.

Ultimately, it doesn't matter. The initial plan to keep the foundational mystery of the show a mystery forever had started to crack almost as soon as the series got started. When the feature-length pilot episode was being produced in 1989, the series had not yet been officially picked up to air; this was a typical practice for new programs up until the streaming era began. As such, the distributor made a deal requiring the pilot to have an ending written and shot for possible theatrical distribution should it not go to series. Thus, Lynch and Frost had to come up with some type of ending to the story. Fortunately, Lynch could do some of his all-time greatest work when given limitations such as these: not only did this result in the creation of the series' infamous "Red Room" scene, but similar circumstances also resulted in him turning the "Mulholland Drive" pilot into a brilliant, eternally enigmatic film about a decade later.

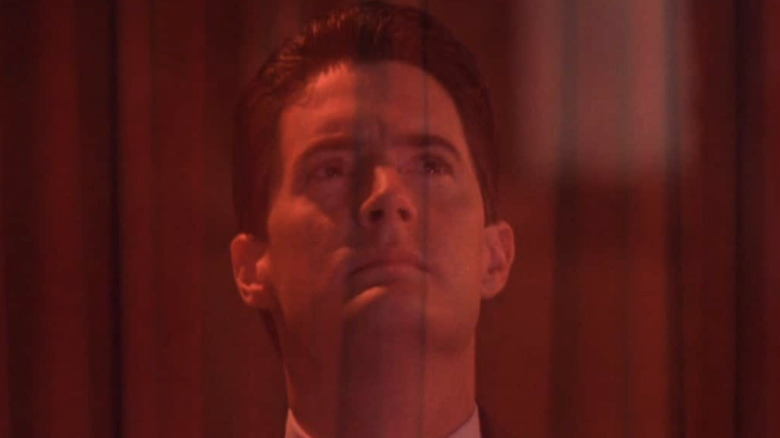

With an answer to Laura's murder being essentially part of the show right when it got going, Lynch and Frost sought to find their way back to the core concept that made Lynch excited about doing a serialized TV show in the first place. As the filmmaker told Entertainment Weekly in 2000, "A continuing story is a beautiful thing to me, and mystery is a beautiful thing to me, so if you have a continuing mystery, it's so beautiful. And you can go deeper and deeper into a story and discover so many things." He and Frost incorporated the Red Room scene as a dream Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) has in the show's third episode, they made the killer BOB (Frank Silva) a demon spirit who could possess an unknown assailant, and so on. Ultimately, while Lynch was adamant that "we never intended the murder of Laura Palmer to be solved," Frost was more pragmatic. In his own words:

"I know David was always enamored of that notion, but I felt we had an obligation to the audience to give them some resolution. That was a bit of a tension between him and me [...] It took us about 17 episodes to finally reveal it, and by then people were getting a little antsy."

Twin Peaks and its legacy proves it was the quintessential Not Ready for Prime Time series

Whether it was pressure from Iger and ABC, pressure from rabid fans (Lynch would tell a story about overhearing a viewer complain about being "sick of waiting" for answers), or some combination of the two, Lynch and Frost ultimately chose to reveal Laura's killer when they did, and in my opinion, they did so brilliantly. Unfortunately, "Twin Peaks" had not been built to last beyond that revelation, and the show fell apart. Given how much emotionally and intellectually stimulating material was raised when Lynch returned to direct the season finale (which was, for a time, a series finale), it's possible that had the show been granted a third season, it could've found its footing again. Sadly, however, ABC didn't afford it that chance.

Ultimately, despite Lynch and Frost's hopes, it seems in hindsight that "Twin Peaks" was simply a television show way ahead of its time. If it had been able to produce just six episodes a season (as with its first season) instead of the then-standard 22 (as in its second season), that would've helped, much like it would've benefitted from airing on a premium cable channel instead of a national network. There were other factors that contributed to the cancellation not discussed at length here, of course: the show's cost, displeasure from the fans and casual viewers about certain storylines, and behind-the-scenes drama amidst the principal cast. Whether the cancellation caused it or contributed to it, the end of "Twin Peaks" coincided with a bizarre backlash against Lynch's work. The film in which he tried to both continue and sum up "Twin Peaks," 1992's "Fire Walk With Me," was so reviled upon release that even the likes of Quentin Tarantino derided it, and it wasn't until "Mulholland Drive" that Lynch became a beloved, "hip" filmmaker again by the general public.

Despite the joy and innovation born from the initial series having to find its way through the strange world of prime time broadcast television, it seems in hindsight that "Twin Peaks" was best able to flourish in an atmosphere of total creative control. That's what "Fire Walk With Me" and the 2017 Showtime revival series "Twin Peaks: The Return" demonstrate, as they are now rightfully two of Lynch's most celebrated works. And while a six (or more) season run of "Twin Peaks" may or may not have been great, the truncated life of the series has only made what does exist that much more influential and appreciated. As Cooper once promised, the journey indeed led us to a place both wonderful and strange.