Why Ridley Scott's Kingdom Of Heaven Director's Cut Is The Best Version Of The Movie

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Ridley Scott was on fire creatively at the outset of the 21st century. After a rough 1990s that saw him stumble, at least commercially, with "1492: Conquest of Paradise," "White Squall," and "G.I. Jane," the world-building maestro bounced back in a big way with "Gladiator," "Hannibal," and "Black Hawk Down." Scott had always exhibited a chameleonic ease moving from genre to genre, but deftly segueing from a sword-and-sandals epic to a Grand Guignol romance to a concussive masterpiece of modern combat over the course of two years was an unparalleled feat, particularly while working on such a massive scale.

Scott, then in his mid-60s, appeared to be peaking (it's worth noting that he didn't make his first feature, 1977's "The Duellists," until he was 40). So when he failed to win the Best Director Oscar for both "Gladiator" and "Black Hawk Down" (despite the former winning Best Picture), it felt safe to assume that something even grander was bubbling in the cauldron of his imagination. After taking a blockbuster break with the amusingly off-kilter crime flick "Matchstick Men" in 2003, it felt like that magnum opus was en route with "Kingdom of Heaven."

Four years after 9/11, with the United States making a bloody mess in the Middle East via the Iraq War, Scott decided to drill down into the faith-based root of conflict in the region with a movie about the build-up to the Third Crusade. The very thought of a major Hollywood director tackling this subject jolted the Arab world. Studios had been depicting Muslims as freedom-hating terrorists long before 9/11; now, many filmmakers felt justified in turning them into the force of evil on the planet.

With a production budget north of $100 million and a prime summer release date of May 6, 2005, there was legitimate concern that Scott would feel obliged to give moviegoers a Crusade film that tilted toward the side of the Christians. That he didn't do this was a relief. That he delivered a hollow and thematically muddled epic felt strangely out of character. How could a director who'd been so dialed in over the last five years deliver something so timid? The answer? By getting distracted by test screening responses and second-guessing his instincts. Fortunately, there was still an opportunity to fix the theatrical release of "Kingdom of Heaven." By returning to the editing room, Scott rescued a masterpiece.

20th Century Studios needs to pull the Kingdom of Heaven theatrical cut from circulation

Ridley Scott's Director's Cut of "Kingdom of Heaven" (which he discussed with /Film's Ben Pearson on this week's episode of the /Film Weekly podcast) has been rereleased a few times since it first hit DVD in 2006, which means there's no reason for the truncated Theatrical Cut to still be circulating. And yet it does. If you're keen to rent the film on Prime Video, the compromised, 139-minute version of Scott's film is currently your only option. While I'd like to think that two decades of praise for the 194-minute Director's Cut has made the 2005 release toxic, the vast majority of Amazon subscribers have no idea they have options.

"Hey, this is the movie my movie-nerd cousin is always raving about." Click. A little over two hours later: "No Christmas card for cousin Chet this year, okay?"

How unsatisfying is the Theatrical Cut of "Kingdom of Heaven"? Since 20th Century Studios (formerly 20th Century Fox) has never lobbied review aggregators like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic to create a separate entry for the Director's Cut (as Warner Bros. did for Scott's "Blade Runner: The Final Cut"), the movie currently holds a 40% Rotten rating at the former and a merely okay Metascore of 63 at the latter. Had Fox done more than a brief, awards-qualifying re-release of Scott's cut at the end of 2005 (which only confused Academy members who'd already received screeners of the Theatrical Cut), or built off the positive momentum of the DC DVD release in 2006, the initial mishandling of "Kingdom of Heaven" would, ironically, only be remembered by the people who laud the DC today.

If you've never seen either version of "Kingdom of Heaven," I implore you to skip the rest of this article and find a way to watch the Director's Cut (it was just released on 4K). If, however, you're one of those folks who were turned off by the Theatrical Cut and demand to know how nearly an extra hour of footage could turn an interesting failure into one of the best films of the last quarter century, read on.

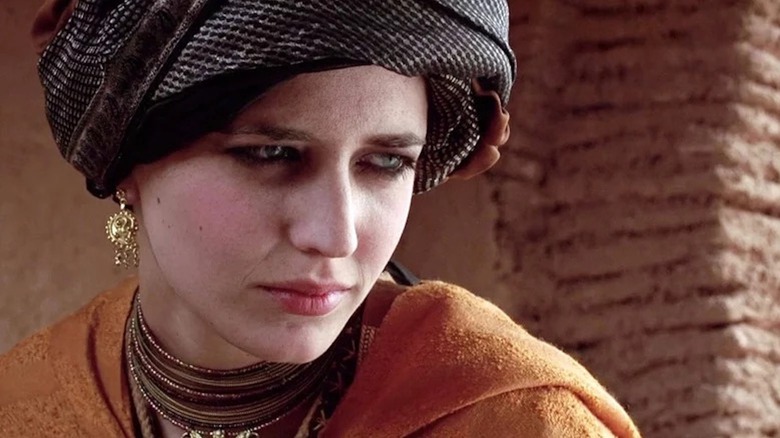

Eva Green owns the Kingdom of Heaven Director's Cut

I first saw "Kingdom of Heaven" at the dearly missed Arclight Hollywood on opening day in 2005, and remember feeling like I'd just watched the proof of concept for Ridley Scott's "Lawrence of Arabia." Here was an ambitious adventure about Balian (Orlando Bloom), a young French blacksmith who, still mourning the death of his wife, inexplicably murders a priest (Michael Sheen) and joins his estranged Crusader father (Liam Neeson) on a journey to the Holy Land. Balian is not a true believer, but, rather, a seeker. He wants to improve the lives of the people who toil on his father's estate in Jerusalem, and expresses disgust at the savagery of the Muslim-hating Knights Templar.

The Director's Cut of "Kingdom of Heaven" reveals that the priest, who is actually Balian's half-brother, desecrated the corpse of our protagonist's dead wife (who killed herself after a miscarriage). From this point, Balian is a haunted man desperate for purpose, which he finds by teaching his dependents how to irrigate the land. At the same time, he falls in love with Princess Sibylla (Eva Green), the sister of leper King Baldwin IV (a masked Edward Norton) and a woman who is mired in a loveless marriage with the power-mad, Templar-friendly Guy de Lusignan (Martin Csokas).

I'd like to say Bloom is the biggest beneficiary of Scott's cut, but Balian is such a gloomy Gus that he's never allowed to do much more than glower. Green, however, comes vibrantly, tragically alive as a miserably married woman whose life is her son — and when she realizes her boy is doomed to suffer as mightily as her brother has through his soon-to-end life, she euthanizes him as painlessly as possible. This 17-minute subplot was completely excised from the Theatrical Cut, which basically turned Sibylla into little more than a flirty distraction for Balian. It also cost Green a slam-dunk Best Supporting Actress nomination.

When you empathize with or, at the very least, understand with the characters' complicated motivations, the climactic battle sequence roars as if the fate of the world hangs in the balance — which, nearly a millennium later off-screen, it still does. What's different now is that people possess weapons that can wipe out those who worship the wrong god. And to the victor, they maniacally reason, goes the spoils of the Holy Land — which, as King Baldwin IV explains, must always be a place for believers and even non-believers. "All are welcome in Jerusalem," he says. "Not because it is expedient, but because it is right." That our inability to understand this has resulted in an ongoing genocide makes "Kingdom of Heaven" more relevant than ever.