John Wayne's Greatest Contribution To Westerns, According To Himself

It is difficult to think of a movie star who did more to dictate the course of motion pictures in the United States during the 20th century than John Wayne. The Iowa native, who owes his acting career to John Ford and Tom Mix doing legendary USC football coach Howard Jones a minor favor, slugged it out as a contract player throughout the 1930s until, at tail end of the decade, he twirl-cocked a Winchester rifle as the Ringo Kid in "Stagecoach." That moment, that movie, changed the Western forever. Before Ford's masterpiece, the genre was basically pulp cinema; after it became a massive hit, Westerns acquired the power of myth.

Wayne firmly believed Westerns existed to tell tales about the pursuit of America's manifest destiny. Wayne was so serious about this that, late in his career, when Clint Eastwood approached him about co-starring in a Western together, he wrote a letter upbraiding his oater heir apparent for having sullied the genre's purity with the dark and violent "High Plains Drifter." As far as the Duke was concerned, he wasn't just a Western star. He was Westerns.

This led to a good deal of humorlessness and, at times, overstatement about his pioneering accomplishments within the genre. Only a fool would question's Wayne importance as a Western star, but other actors — most notably Gary Cooper, Henry Fonda, and James Stewart — were as integral to its development over the 1940s and 1950s. So when the Duke claimed, for instance, that he revolutionized the way a hero fights in a Western, many grains of salt must be taken.

John Wayne fought hard and dirty

Wayne was fiercely protective of his image. Though he allowed directors he trusted (namely, John Ford and Howard Hawks) to cast him as protagonists who weren't entirely sympathetic, there were things he simply wouldn't do. When the script of Wayne's final film, "The Shootist," called for him to shoot an assailant in the back during the climactic gunfight, the star put his foot down. Though his gunman character had miraculously survived to see old age despite having killed dozens of men (which likely required him to commit quite a few dishonorable actions), Wayne the big-screen icon refused to shoot a man who couldn't see the bullet coming.

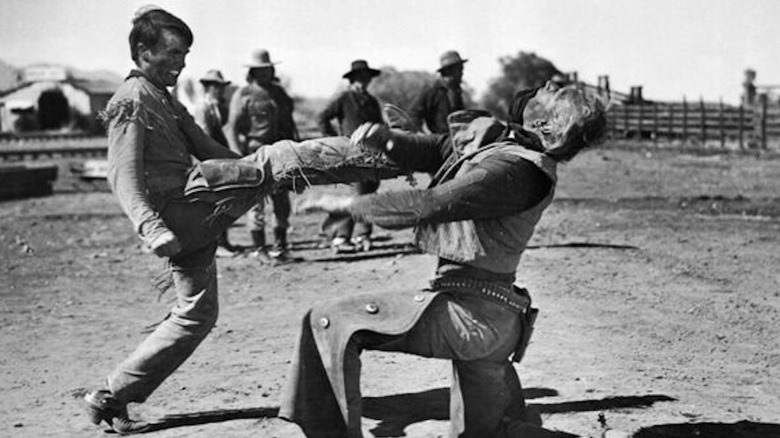

Oddly, this honorable mindset didn't apply to Wayne's on-screen fisticuffs. When it came to throwing down with a bad guy (or, in the case of "Red River," his adopted son), Wayne made it clear that his characters would do anything to come out on top of a scrap. In fact, according to the Duke, his no-holds-barred philosophy regarding hand-to-hand combat was a game changer. According to an interview excerpted in a Literary Hub essay by Tyler Malone:

"Before I came along it was standard practice that the hero must always fight clean. The heavy was allowed to hit the hero in the head with a chair or throw a kerosene lamp at him or kick him in the stomach, but the hero could only knock the villain down politely and then wait until he rose. I changed all that. I threw chairs and lamps. I fought hard and I fought dirty. I fought to win."

When it came to fighting, Wayne was a lot of talk. He threatened to level Robert Duvall on the set of "True Grit," and evidently wasn't shy about using his considerable size (he stood 6'4" and weighed in the neighborhood of 220 lbs when healthy) to intimidate anyone who challenged him. Wayne's greatest contribution to on-screen fighting was in studying pugilists like Jack Dempsey, and learning how to fake a jaw-shattering punch.