Civil War Ending Explained: Got The Shot

Living in a country where people's basic human rights are being stripped down or removed on a regular basis, where hate and prejudice are alive and well, where violence can erupt at any moment in almost any location — it feels increasingly strange to call being an American a privileged and lucky thing, but the fact remains that it is (for now, at least). In comparison to the many war-torn countries that have suffered open conflict in their streets at various points in time (including, yes, this very moment), Americans haven't had to endure the horror of invasion, occupation, or open warfare as a way of life for many generations, basically since the American Civil War of the 1860s.

This is not to say that Americans are ignorant, but rather especially privileged. Being a part of a country that has generally maintained political, cultural, and military dominance over the world for the last century, America's more thoughtful cinema in relation to war has tended to either look inward at mistakes and injustices we've committed elsewhere or create an external fantasy of "it could happen here," whether that be post-apocalyptic films (zombies or otherwise) or movies like "Red Dawn."

"Civil War," the latest movie from the English filmmaker Alex Garland, essentially falls into the latter category. Yet, as its marketing campaign and button-pushing bits of dialogue and images indicate, the prospect of another, actual civil war breaking out in this country feels dangerously possible, especially given the events of the last decade and change. However, for better or worse, "Civil War" is not a directly political film, nor is it apolitical, given the theory of cinema-as-politics in terms of creative choices made or not made. Instead, the movie is the latest in Garland's cinema of reality transformed into liminal spaces. Just as "Ex Machina," "Annihilation," and "Men" ventured into literal uncanny valleys, "Civil War" explores the horror of America transformed into a place its characters — and its audience — do not recognize, and yet must reckon with. It's a film of observation, with people whose job it is to observe as its protagonists.

My foolish Americans

The closest "Civil War" comes to piggybacking on topical issues directly occurs during its opening moments, which sees real-life footage of recent riots, protests, and other incidents (obtained from some highly unsavory sources) intercut with this film's President (Nick Offerman) feebly rehearsing a George W. Bush-style "mission accomplished" public address. The President is making a statement regarding the civil war that has been raging in the USA for a while between the Western Forces (an alliance of California and Texas) and the Loyalist States, which make up most of the rest of the country. Mentioned in passing during the film are the New People's Army (which seems to account for a chunk of the Pacific Northwest) and the Florida Alliance, which the President is gleefully crowing on television about the U.S. Army having recently defeated.

Of course, this President's televised spin doctoring can only cover up so much. As Lee (Kirsten Dunst), a world-weary photojournalist, sits watching the President's address in her New York City hotel room, a series of explosions go off in the near distance. The WF are continuing their battle to take the country (whether their ultimate aim is to obtain power or simply to force the Loyalists to grant them succession is unclear), and that doesn't mean that violence in America is only relegated to those battles. On the contrary, casual violence, as well as organized riots (whether or not they begin as protests), still occur regularly, and it's at one of these protests-turned-riots in Brooklyn that Lee attends as a press photographer, seeing a young woman also attempting to take shots of the altercation with her film camera. Pulling her away from danger, Lee gives the woman, Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), her protective vest, insisting that she keep it from now on.

Never get off the boat

Later, at Lee's hotel, she and her journalist colleague, Joel (Wagner Moura), discuss their plans to make their way to Washington, DC in order to hopefully take a photo of and interview the President, respectively. When another old friend of theirs, Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), overhears their plans, he initially tries to talk Lee out of going, knowing the literal and figurative danger zone they'll be driving into. However, during his protestations, Sammy (who Joel describes as working for "whatever's left of the New York Times") realizes what Lee and Joel know: this is the only big story left to file, even if, as he warns, there may no longer be anyone left to file it with once it's obtained.

Like a moth to a flame, Jessie — a self-confessed fan of Lee and her work — turns up at the hotel, thanking Lee for saving her life earlier and trying to insinuate herself into the photographer's life a little more. She's ultimately successful, as Lee discovers the next morning that Joel is letting her tag along since Lee said the older, infirm Sammy could come with them earlier. Like the soldiers in Coppola's "Apocalypse Now" (or, perhaps more pointedly, Garland's "Annihilation"), the foursome take off in their "PRESS"-labeled van into the once-familiar, now-strange American landscape.

As if to prove that uncanny, threatening strangeness, the group stops off at a gas station where Lee has to offer the proprietor $300 Canadian in order for them to get half a tank and one additional carton of gas. Exploring the station's now-defunct car wash, Jessie discovers the station owners have strung up two alleged looters, one of whom used to be an old high school classmate of his captor. Jessie is stricken numb with shock and fear; Lee coldly asks the man to take a photo with his victims.

After Jessie has a small breakdown following the incident, Lee has Joel pull over to a destroyed shopping mall where a helicopter had crashed long ago, teaching Jessie that it'll make a good image. The two women reconcile their differences, even as Jessie learns about Lee's hardened approach to morality born through years of field experience. When Jessie asks if, should she be shot and killed during their journey as Lee seems to think that she will, Lee would take a picture of her body, Lee says she would without hesitation.

Life during wartime

During a brief lull on their journey, Lee and Sammy watch tracer fire lighting up the night sky in the distance while discussing the state of things. As Lee observes, all of her prior war photography overseas was something she saw as "sending back a warning" to America, a series of omens that she believed read "don't do this" which have clearly gone unheeded. Where Lee is a woman reaching her middle age, seeing how almost no lessons have been learned from her life's work, Jessie is a woman who still believes in the power of information and capturing a real moment. She captures as many moments as she can during a skirmish the group decides to cover, including an incident that recalls the finale of Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket," where a wounded enemy combatant, mewling for help while in pain, is coldly murdered once the victorious soldiers find him. A moment later, another image recalls Kubrick's other anti-war screed, "Paths of Glory," where Jessie witnesses the WF soldiers march out and execute three men with bags over their heads while Joel has a laugh with another soldier nearby.

Coming upon a relief camp further down the road, the group pulls over to rest and recover from the day's battle, and Lee and Jessie begin to connect beyond their initial fan/hero relationship. Revealing that she knows little about Lee's life beyond her Wikipedia page, Lee tells Jessie about her history, and the two discover that they have similar backgrounds. Both Jessie's family in Wyoming and Lee's family in Colorado live on farms where they pretend that "none of this is happening," their family's blissful ignorance only adding to the cognitive dissonance of America's constant state of strife.

The oasis

Speaking of cognitive dissonance and citizens pretending the civil war isn't happening, the Press van rolls into a small town in which no semblance of decay appears, a doubly strange phenomenon given that so much of America in the film so far feels akin to a George A. Romero (or, to reference another prior Garland script, "28 Days Later") landscape.

Pulling up to a shop on the town's main street, Joel briefly interrogates the shop clerk, wondering if she and the townspeople know that there's a war going on. She confirms, but shrugs, explaining that the town has made a decision to pretty much "stay out of it." Jessie convinces a reluctant Lee to try on a dress, and the woman looks at herself wearing the garment in the mirror; it's the first time in a long time she's seen herself wearing anything but comfortable, on-the-go clothes.

Perhaps seeing that Lee is slightly succumbing to the town's siren song, Sammy calls her over while the two share a cigarette. Indicating that she should slyly sneak a look at the roofs of the surrounding buildings, Lee sees snipers posted on every roof, revealing just how this town is free to be so lackadaisical. "We wouldn't have liked it here, anyway," Sammy says knowingly.

Tourists, trapped

If the "town without war" acted as a sort of honey trap for our journeying heroes, they soon come upon a far more blunt kind of trap. In the middle of a lonely road in a large clearing lies the body of a dead soldier, surrounded incongruously by a "Winter Wonderland" tourist trap display. Sensing danger, Lee pulls out her telephoto lens, but can't see anything around. Driving forward cautiously, Joel hits the gas once bullets hit the van's windshield and side.

Fleeing out of the van to cover, the group comes upon a pair of soldiers who are similarly pinned down by the sniper, who's firing at everyone from the comfort of a large mansion several yards away. Joel, ever the reporter, tries to extract information from the soldiers, asking them who's shooting at them, why, and which side are the soldiers fighting for. The soldiers themselves break everything down to brass tax: "We're trying to kill the people who are trying to kill us."

This viewpoint is all at once exceedingly simple and distressingly obscure, not unlike "Civil War" itself. A debate on merit aside, it's an intentional design, as Garland states in the film's official press kit: "I don't think America or the rest of the world is at danger of the clear demarcations of the previous Civil War. That's not the risk the world faces. We are facing a disintegration risk."

This notion of a "disintegration risk" is key to Garland's work, as every one of his films involves an assumed state of reality transforming into a new, heavily uncertain status quo. Lee, Jessie, Joel, and Sammy aren't attempting to put a particular spin on the events they're capturing: they, too, are trying to inform as much as possible, maybe even themselves more than some nebulous audience out in the world. As one of the soldiers says after taking care of the sniper in the mansion, "I have some good news." For the group, at this moment, that's all they need to know.

The wrong kind of American

Unfortunately, as fair and balanced as the journalists are attempting to be while doing their jobs, that doesn't mean others with far more radicalized outlooks aren't an active threat, as the group comes to learn the hard way. When another van rapidly approaches the group's, it turns out that the passenger is a good buddy of Joel's, Tony (Nelson Lee), who instructed his driver pal, Bohai (Evan Lai), to follow the group to DC in order to potentially beat them to the story. For a few moments, the two groups enjoy some frivolity, with Tony jumping into our heroes' van while both are still driving at top speed (something Jessie exuberantly tries out by jumping into the other van).

After Bohai and Jessie take off down the road, they suddenly seem to disappear, leading Lee to initially suspect some foul play. Her instincts are right, even if her suspicions turn out to be worse, as the group finds Bohai's van forced over and abandoned near a lakeside farm. They approach some soldiers dumping a load of corpses into a mass grave, and it becomes apparent that these soldiers do not belong to any particular army. Despite Sammy's protests, the three approach the leader (Jesse Plemons), explaining that they're American journalists and asking that their colleagues, who are being held at gunpoint, be set free.

"What kind of American are you?" asks the leader, and it soon becomes clear that Lee and Jessie's answers of Colorado and Wyoming are acceptable, while Tony's answer of Hong Kong is not. Just as it seems the leader is about to murder Joel for being from Florida, Sammy arrives in the van, running the man down and rescuing the group, though unfortunately not before Jessie spends a horrifying moment in the middle of the mass grave, and not before Sammy is hit by a stray bullet while they flee the scene.

Coup world

As Sammy passes away, bleeding out in the back seat of the van as the group approaches the front lines at Charlottesville, he's treated to a more pleasant type of alien landscape: the serene natural beauty of America, a portion untainted by the abject horrors the group has just witnessed. Lee, Joel, and Jessie hang onto that vision tightly, as Joel is told by an embedded journalist in the WF camp, Anya (Sonoya Mizuno), that the WF Army have broken through to DC, which means the President will either be dead or extracted before the group can get there. As Lee solemnly cleans off Sammy's blood from the back seat, she, Jessie, and Joel reflect on how Sammy seemingly died for nothing.

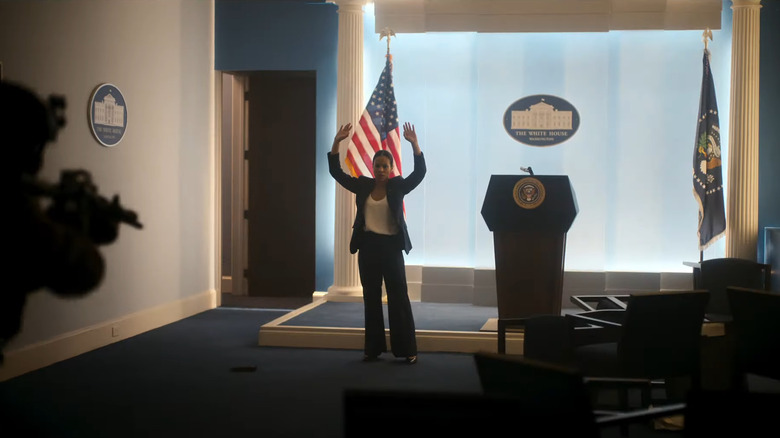

Still, the group pushes forward, joining the WF Army on their tear through DC. Initially, it seems Jessie and Lee have traded places; where Jessie is now boldly venturing into the middle of skirmishes looking for the perfect photo, Lee seems almost frozen with the weight of loss, despair, and terror, as Joel tries to keep her mobile so she isn't hurt by gunfire or explosions. At the White House, the WF soldiers spot what they think is the President climbing into a getaway car, and the army focuses their efforts on a fleeing fleet of vehicles. This event stirs Lee awake from her meltdown, her old instincts kicking in: she realizes that the President isn't actually in any of those cars. Leading Jessie and Joel into the White House, she's followed by a small platoon of soldiers while the rest of the army lights up the city's streets, killing the President's staff as they pour out of the vehicles.

Friendly fire

As the WF Army tears through the White House, taking down various secret servicemen and aides, Lee, Jessie, and Joel are right beside them, documenting as much as they can despite the danger. Lee, in particular, seems reinvigorated after her earlier breakdown, remembering her role in the world and seemingly renewed in her belief in it. She has also, of course, become a mentor and surrogate mother to Jessie, who seems to be quickly following in Lee's footsteps.

Eventually, the fate Lee once predicted for Jessie comes for her instead, even though it's partially her choice — when Jessie is left momentarily in the line of fire, Lee pushes her out of the way, only to catch the bullet herself. Jessie, now a professional photojournalist, captures the moment of her mentor's death on camera. The fact that Lee has been killed by a bullet fired by a White House official only makes the incident that much more strange and tragic.

Journalists do occupy a strange place in society, albeit a necessary one. After all, it was Lee's instincts that led the WF Army into the White House where the President was secretly hiding. Yet Lee, Jessie, and Joel represent the citizenry of the nation on-site; if nothing else, they're witnesses to history so that the events can be known and interpreted later. As the Army captures the President at gunpoint, Joel screams at the soldiers to wait a moment: "I need a quote," he explains, not wanting this incident to pass unobserved, not wanting his colleagues to have died for nothing. The President weakly mewls, "Don't let them kill me." Joel is satisfied: "That'll do."

A thousand words

It is Jessie who takes the photo that becomes the final image of the film, developing through the end credit roll: the WF Army surrounding the corpse of the one-time President of the United States. In an interview with /Film's Jacob Hall, Garland had this to say about Hall's proposal that the image will become a historical watershed photo for the future:

"That had never occured to me until you stated it. I was just showing war photographers doing what they do [...] and because they're good at what they do, they capture iconic moments. [...] That is one of the things that really interests me in this subjective thing, in this offering up narratives and people bringing themselves to the narrative, that is actually a perfect example of what I'm talking about."

As the totality of American life has demonstrated, but especially in the last several years, there are billions of individual perspectives on history, whether it's far in the past or is currently happening. The job of the journalist — and the artist — is observation, perhaps even more than commentary. Truth is subjective, but it is also finite, a paradox we all have to live with and reconcile. Images are perhaps the closest thing we have to objective truth: they are, after all, worth a thousand words.