Every Director's Cut You've Ever Seen Owes Its Existence To The Twilight Zone

The term "auteur theory" was first coined by American critic Andrew Sarris, a phrase he extrapolated from the essays published in Cahiers du Cinéma in the early 1950s by the founding members of the French New Wave. Auteur theory posited that a director stands as the final authorial voice behind a feature film, and not the writer, the editor, or any of the other filmmakers. While many critics over the years have objected to auteur theory (Pauline Kael famously hated it), the language of referring to a film's director as its "one author" has become the default used by pundits and journalists to this day.

Throughout the 2010s, there was a visible push-and-pull when it came to auteur theory. While plenty of striking, important directors put out unique, idiosyncratic works, massive studio franchise pictures stayed at the commercial fore, and individual directors were subservient to all-powerful Higher Ups. For the films in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, or the pictures put out by Disney, the studio was the auteur, not any of the individual filmmakers.

For the better part of a century, mainstream film and television have been more beholden to the latter corporate mold than anything auteur-driven. Directors can construct an intimate, important, personal work, but the studio often has final cut.

Variety's obituary of director Elliot Silverstein mentions an episode of "The Twilight Zone" he directed called "The Obsolete Man" (June 2, 1961). It seems that Silverstein shot the episode the way he wanted but then saw the studio recutting it to its liking. A few years later, burnt by the experience, Silverstein presented a complaint to the DGA and the organization henceforth declared that a director's original cut, before studio tinkering, should be called a "director's cut."

A new cinematic concept was born.

The Obsolete Man

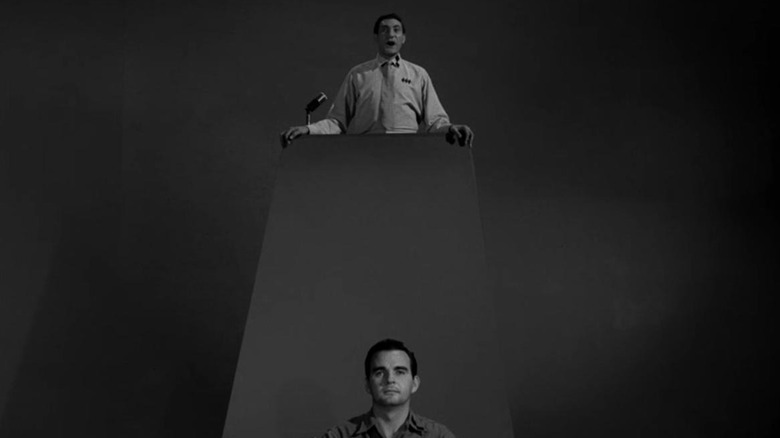

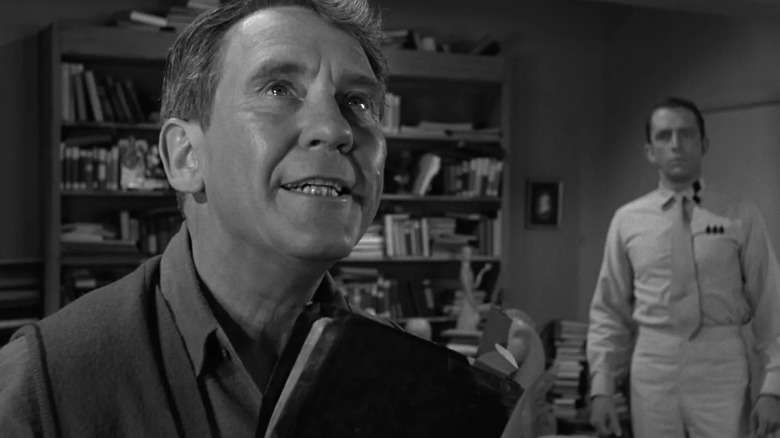

"The Obsolete Man" takes place in a dystopian future wherein a bitter, strict, ultra-Communist government has taken control of the world. Burgess Meredith plays a gentle librarian named Wordsworth whose profession — and, gasp, belief in God — are considered obsolete by the government. In this future, obsolete humans are put to death. Wordsworth is allowed to select his mode of execution.

He chooses to be trapped in a locked room with a time bomb while his last moments are televised worldwide. Wordsworth also lures the State's Chancellor (Fritz Weaver) into the room with him before explaining about the bomb and the cameras. The Chancellor cannot escape without losing face. Wordsworth uses his last few moments to lecture the Chancellor on the power of compassion.

The episode ends when the Chancellor escapes ... but then is apprehended and put on trial. The Chancellor is declared obsolete and beaten to death by the State. Rod Serling's closing narration lays it bare: "Any state, any entity, any ideology which fails to recognize the worth, the dignity, the rights of Man ... that state is obsolete."

In Marc Scott Zicree's invaluable book "The Twilight Zone Companion," Silverstein recalls the editing issue that got him in trouble. "The Obsolete Man" was very abstract, taking place largely in an expressionistic courtroom space lined by a chorus of scowling Nazi-like judges. Silverstein wanted the judges to "sing" their disapproval to their plaintiff, the Chancellor, moaning in an eerie, nightmarish fashion before dragging him across a long table and killing him.

The episode's editor wanted to cut a few moments of "singing" before seizing the Chancellor. No, Silverstein said, it needs to build. He and the editor fought over it.

The fight with the editor

Silverstein recalled:

"He showed me this rough assembly and he had them moving immediately, as soon as they started to growl. I said, 'No, no, you don't understand. You see, in the master shot I have them standing there.' He said, 'Well, so what?' I said, 'Well, that is how I staged the scene. I want them standing there until their voices reach a certain pitch. The master is a message to you and to everybody else.' He said, 'Well, I don't want to cut it that way.' I remember very clearly, I felt my temperature and my blood pressure go up. I said, 'You what?'"

It was a matter of pacing, coverage, and clarity, but the editor Silverstein butted heads with refused to see it his way. The editor seemingly wanted to remove the more abstract part of the scene and skip straight to the action. Eventually, Silverstein had to appeal to "The Twilight Zone" producer Buck Houghton to work out a compromise. He explained:

"[I]t was a compromise. It never did what I wanted it to do, which was to have everybody in the audience saying, 'Why aren't they moving? Why are they all just doing this strange thing?' And I wanted the sound of the voices on chorus to rise until the hackles rose on the back of your neck. So, the compromise was, I suppose, the best of what Buck could achieve in trying to be fair to an editor with whom he had to work again and a director who was being very adamant."

Silverstein would remember this experience at the next meeting of the Directors Guild of America.

The Directors Bill of Rights

According to the Variety obituary, Silverstein learned during the "Obsolete Man" editing kerfuffle that directors can oversee the shooting of a TV episode but would only be permitted to see a rough cut thereafter. Once the rough cut was screened, editing was then overseen by an associate producer, who could follow a director's suggestions ... if they wanted to. Silverstein was outraged by his lack of creative control over "The Obsolete Man" and expressed his concerns to George Sidney, the president of the DGA. Other directors, he learned had gone through similar experiences, having their work recut without their input. Silverstein, along with Sydney Pollock, Robert Altman, and a few others, sat down to draft what would become a Director's Bill of Rights. The first notion of a Director's Cut was embedded in the Bill.

The Director's Bill of Rights was published in April of 1964 and made explicit something that we now, in the 2020s, understand to be a fundamental part of filmmaking. One of the articles in the Bill stated:

"The arrangement of the recorded images and sounds in a relationship the Director considers proper shall be known as the 'Director's Cut.' It is the Director's creative right and obligation to prepare this cut, and he must be given the time he deems necessary to fulfill this function."

A studio may ultimately have final cut on a project, but the Director's Bill of Rights states that a filmmaker should be allowed to complete a project as they see fit before a studio starts monkeying with it.

Director's Cut-o-Rama

In 1980, a Director's Cut of "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" was released in theaters, and the cat was out of the bag. The public now understood that Director's Cuts were separate works from theatrical cuts and that studios were regularly interfering with auteur theory. The issue arose time and time again, with filmmakers noting that their "pure" visions were constantly being altered against their will. By the time Ridley Scott's "Blade Runner" came around, it was clear that a director and a studio had very different visions. "Blade Runner" has notoriously been released several times, each time with a slightly different edit.

No film, it seems, could be deemed complete, and audiences became intimately familiar with the fineries of editing and the politics of filmmaking.

In the 1980s, when the home video market began exploding, Director's Cuts became even more common. There was now a market for alternate edits that was clearly separated from a theatrical experience. This practice became even more prevalent in the late '90s and early '00s with the advent of DVDs, which often contained deleted scenes and alternate takes as special features. We were living in a world wherein the public at large always understood that a theatrical release was not the final word on a film and that a Director's Cut would likely be coming down the pipeline soon.

Just recently, Ridley Scott's 2023 historical epic "Napoleon" was recognized by critics and even the director as being incomplete. Scott noted that his Director's Cut will be made available on Apple TV+. Scott would likely not have the leeway or the venue to display his Director's Cut were it not for the outrage and the wherewithal of Elliot Silverstein and his bad experience shooting "The Obsolete Man."