Data's Emotion Chip Drove A Wedge Between Brent Spiner And Star Trek's Writers

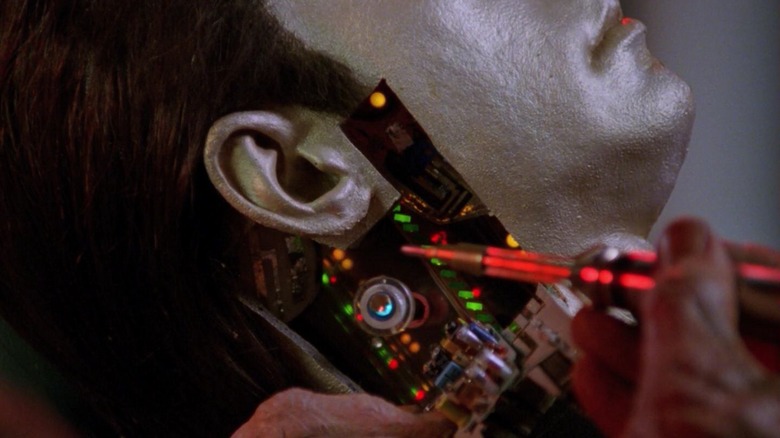

Throughout the seven seasons of "Star Trek: The Next Generation," the android Data (Brent Spiner) often struggled with his inability to connect with his crewmates. Unlike Data, his organic peers were all emotional beings who could laugh, get angry, and intuit friendly interactions via their feelings and social acumen. Data had no emotions, at least not demonstrably, and had to rely on analysis and study to understand humans. Data longed to be human and often asked his friends to explain their baffling idiosyncrasies. Data's emotionlessness was not a flaw but a design choice by his creator.

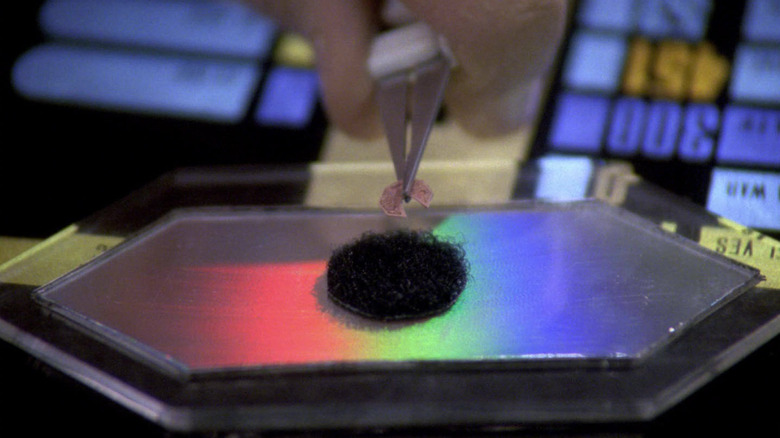

Later in the series, Data secured an emotion chip built specially for him by his presumed-dead creator. At first, he was afraid to install it, but after a prank gone awry in the 1994 film "Star Trek: Generations," Data finally decided to give himself the emotions he had been longing for. It's a pity that Data's new emotional journey was relegated to a mere subplot in "Generations." One might think that having emotions for the first time would be a more significant event for the character.

At the end of "Generations," Data announced that the emotion chip merged with his neural net and couldn't be extracted. In 1996's "Star Trek: First Contact," it seems he learned how to turn his chip off and on with a flick of his head. By 1998's "Star Trek: Insurrection," he could — and did — remove it entirely.

In the oral history book "The Fifty-Year Mission: The Next 25 Years: From The Next Generation to J.J. Abrams," edited by Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross, the "Insurrection" revelation that Data could just take out his emotion chip didn't sit well with the actor. What kind of character, Spiner wondered, was Data even supposed to be anymore?

Data's emotion chip travails

Throughout "Insurrection," Data doesn't have his emotion chip at all, having left it on board the U.S.S. Enterprise-E while he went on an extended study mission on the Ba'ku homeworld. The bulk of the film takes place on that planet, and Data remains his old-fashioned, emotionless self. He is back to being innocent and childlike and unable to read the emotional states of others. In brief, the filmmakers were erasing all the dramatic development made for Data in the last two films.

According to producer and screenwriter Michael Piller, Brent Spiner hated that. Piller claimed — to Spiner — that the character needed to resemble who he was on the small screen for the benefit of audiences who hadn't necessarily seen "Generations" or "First Contact." Piller said:

"Brent had a very strong feeling when he read the script that I was treating his character as though the last two movies didn't exist. To be honest, he was right. Jonathan Frakes and I were determined to bring back that Pinocchio quality from the series. My argument to Brent was that the big-screen audience had never had an opportunity to see that quality of the character Data that we had all fallen in love with in the first place. The discussion continued until the very last day of shooting."

Spiner was also quoted in "The Fifty-Year Mission," and he seemed wearied by the issue. The emotionless Data was a regression, but the emotional Data was also not adequately explored. The only thought was, "Data has emotions now, and that's that." Spiner said: "You can't keep beating something over the head. In the last two films we dealt with Data's emotion chip, and the feeling was enough is enough." No more emotions. Safe, backward movement is better.

The Rhoda Effect

Michael Piller likened Data to the title character in "Rhoda," the 1974 spin-off of "The Mary Tyler Moore Show." Piller saw Rhoda, played by Valerie Harper, to be defined by her singlehood. She was always interested in romance but never managed to make her relationships work. Eventually, Rhoda did get married at the end of the show's second season. Because Rhoda finding romance was anathema to the character, the showrunners found an excuse to keep her and her husband Joe (David Groh) apart. Eventually, the two divorced.

Piller wanted to avoid giving Data a Joe, as it were. Data wasn't permitted to get everything he wanted, as his longing was a more vital part of the character.

Brent Spiner, too, acknowledged that familiarity was important to "Star Trek," although he doesn't seem to acknowledge that as a positive quality. Still, Spiner was quoted as saying:

"Part of what brings people into a 'Star Trek' movie is that it is familiar territory, not the unknown. There are certain slight variations from film to film, but they're not all that different. None of the nine [movies to date] are remarkably different from any other of the nine or any of the hundreds of episodes. There's a real similarity to them, and that's what brings people back."

Some Trekkies might take exception to Spiner's comments, arguing that the nine "Star Trek" feature films made from 1979 to 1998 do indeed explore different themes and have unique tones. "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" is contemplative and epic, while "Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan" is more action-oriented. But one can understand Spiner's bitterness when one remembers that he was tired of playing Data at this point in his career.

Spiner's indifference

Brent Spiner, however, was also thoughtful about his character. Although he noted that "Star Trek" was often "samey" and that its samey-ness was a vital part of its continued existence, he also did note that Data did have the ability to grow and change. By the end of the series, Data was meant to be more human than he was at the start. Spiner said:

"Data has certainly changed from the first episode of the series, but that was a design built into it. Gene Roddenberry wanted this character to start as a sort of blank tablet, and his idea was that by the end of the day he would be as close to being human as possible ... and still not. That's the way it's been written all the way down the line. They try to have Data experience or grapple with every aspect of the human condition."

One of the plot points in "Insurrection" is when Data bonds with a young Ba'ku child who asks him if he ever had a conventional childhood filled with play and silliness. Data realized he hadn't, having been built in an adult body. That was Spiner's "hook" into Data for "Insurrection." He said:

"In this particular film he's dealing with locating the inner child. That's a part of the human condition he hadn't dealt with yet. This one went in a certain direction with the first two films where Data changed by virtue of having an emotion chip."

Spiner ended with a word for the haters: "Some people liked it," he said, "some people didn't. I don't really care."

Data would eventually return in "Star Trek: Picard" with Spiner, 74, reprising the role. He did indeed become more human than ever on that series.