The Mask Of Zorro At 25: An Oral History Of The Last Old School Blockbuster

His predictive sci-fi action film "Minority Report" was still several years away, but in 1997, Steven Spielberg could already see the future.

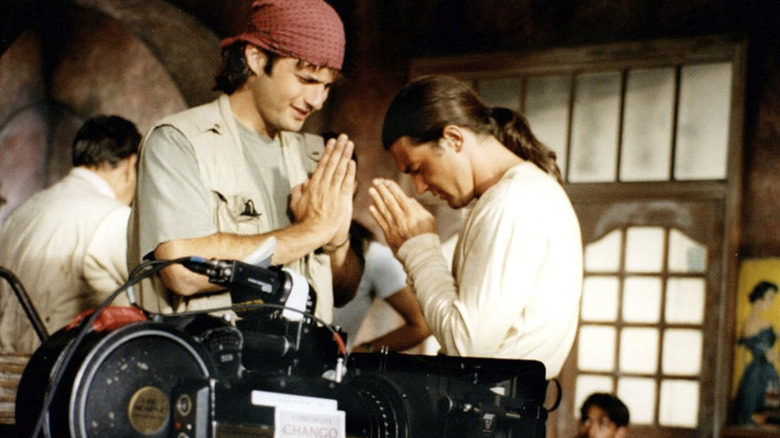

At that time, Spielberg was an executive producer of "The Mask of Zorro," and during production, he sensed something in the air. In an interview earlier this year, "Zorro" star Antonio Banderas recounted what the famed filmmaker told him:

"Steven Spielberg said to me once when we were shooting, 'This is probably going to be one of the last Westerns shot in the way the Westerns were shot in the old days, with real scenes and real horses, where everything is real, real sword fighting, no CGI.' Everything was practical. And he said, 'But things are going to change. They're going to change and they're gonna change fast. And so you should be proud of this movie.' And I am, probably even more now than at the time that I was doing it."

Spielberg's prediction came true. While there have been a handful of practical Westerns shot in the years since, none at this budget level have managed to achieve a similar sublime combination of style, stunts, sexiness, and swashbuckling. "The Mask of Zorro" felt special when it came out. The casting is pitch perfect, the script is terrific, the score is top notch, the stunt work is out of this world — everything about it just works. As an elegant blending of origin story, "passing the torch" tale, and superhero action flick (despite Zorro technically not being a superhero), this movie should serve as the gold standard for modern movie studios obsessed with intellectual property. An argument could be made that Hollywood still makes movies in this vein these days, but it sure as heck doesn't make them in the same way.

25 years after its release, I wanted to learn about how "The Mask of Zorro" came together. Over a dozen people who worked on the film told me about the film's multi-year journey to the big screen, the directors who came and went, a sickness that swept through the crew during production, government corruption, failed explosions, and much, much more. This is the oral history of "The Mask of Zorro."

Chapter 1: Earliest days

Writer Johnston McCulley created Zorro in 1919. After successful movie adaptations in 1920 and 1940 starring Douglas Fairbanks and Tyrone Power, Zorro headlined a live-action Disney TV series in the 1950s. But in the years that followed, the character faded for American audiences. By the time the late 1970s rolled around, the masked hero was all but forgotten in the pop culture zeitgeist.

John Gertz, co-producer: I'm the CEO and president of a company called Zorro Productions. As such, we own all the rights to the character — all the copyrights and trademarks. And when I took over the property back in the late '70s, those rights and maybe 25 cents might have gotten you a cup of coffee somewhere, because coffee was cheaper in those days. It was considered to be an old washed-up thing. So together at that time with my twin sister, Nancy Larson, she and I started developing ideas and concepts for Zorro and hitting the streets in Hollywood and trying to sell them. And we succeeded. We got some TV series up and running and did the film "Zorro the Gay Blade," and so on.

In the late '80s and early '90s, my sister and I decided that maybe it's time for a major motion picture, and we began to develop a concept for it. And my twin sister wrote a screenplay. She's a very good screenwriter, and she wrote a wonderful screenplay, and we decided to shop it in Hollywood. We had a young and aggressive agent by the name of Michael Siegel, and we arranged for an auction. The way it was set up was that we invited all of the producers in town — large studios and independents and so forth — all to pick up their copy of the script at precisely noon Pacific time at the agency office, and we would accept bids on Monday morning. The ploy worked. On Monday morning, we actually had offers come in, but one that we did not receive was from Amblin. Somebody over there sent a simple note, saying, "No, this not a project that we'd be interested in."

We then went down the road with one studio or another for a bit, and suddenly we get a call from the head of TriStar Studios, who said that they're going to make a better offer than anybody. And the crux of it is they've got a filmmaker that's going to knock our socks off. So we went to the table with them, and I spent an entire day, myself personally, in the room with the head of TriStar and the head of business affairs there, negotiating the deal in excruciating detail. But at the end of the day, the numbers worked. But I said to Mike Medavoy, who was the head of TriStar Studios at the time, "The numbers worked, but it's all been contingent on this mystery filmmaker you've got." And he asked everybody else to leave the room, including my agent and everybody on his side. So Mike and I were just alone in the room together, and he put his feet up on the desk and lit a cigar and said, "It's Steven Spielberg."

At that time, he was filming ["Hook"], the Peter Pan movie with Robin Williams and Dustin Hoffman. And apparently Mike Medavoy just went up to Steven and said, "Hey, listen, I've got this Zorro thing. Would you be interested in Zorro?" And Steven said, "Zorro! I grew up with Zorro. I love Zorro. I can't wait to do Zorro." Okay. So whoever it was that rejected it at Amblin had never bothered to ask Steven, apparently.

So then I left the room. I said, "Mike, I got to speak to my twin sister and partner in this." So I left the room to call her, and I said, "Nancy, the numbers work, trust me on that, and the filmmaker they have in mind is Steven Spielberg."

And Nancy, to my amazement, started screaming at me, "Get the hell out of that room. Get out of there. Run to the parking lot, get in your car and don't look back." I go, "What's wrong?" This was the complete opposite reaction from what I expected. And Nancy said, "He's not going to make this movie, and I'm going to be the first one he bumps off the project."

In the meantime, TriStar agreed to pay Nancy a huge sum of money for a script, never mind on top of that, a rights deal for us, for my company. Anyway, so the next thing is Nancy was flown down to Los Angeles to meet with Steven, and she was offered the chance to write the second draft. But she got out of that meeting — Nancy's got a lot of artistic integrity, and she came out of that meeting and said, "You know what, John, make the deal. Steven will make a tremendous movie. I'm sure it'll be fantastic, but I don't share his vision. I don't want to be the writer." Because Steven wanted to do a "passing of the sword" story, a father-son tale, which is a leitmotif that runs through a lot of his work, as I'm sure you know, and Nancy didn't want to tell that story. So she walked out of it. That's the genesis story for the movie.

Randall Jahnson, writer: I started working on it in 1991, and I was in the sort of zeitgeist, I guess you would say, at the time, because the movie "The Doors" was coming out and I was, along with Oliver Stone, one of the screenwriters on it. We shared credit on that. So when that happens, at least ... [this] is last century kind of stuff, but when you have a movie coming out, you're kind of hot. And it's a little bit not unlike professional sports, where you're on a good batting streak or something like that. So your agents will certainly say, "Hey, take advantage of this momentum and let's get the next big gig that maybe can come your way."

I was actually writing something else for another company. And then I got this call from my agent, who said, "Would you be interested in writing a revamp of Zorro?" That's quite a turnaround from "The Doors." And I thought, "Well, yeah, maybe." And they said, "It's for Spielberg." And I said, "Oh, I'm in. Please." So we had to put a pin in what I was currently working on, which was about the shootout at the O.K. Corral, which is a whole 'nother story, and then ask, "May I please have an exception to go work for Steven Spielberg on this?"

John Gertz, co-producer: It takes a long time to get a movie made, but it was shocking how long it took ... the agreement I entered into then was dated 1991. I think it was April, if I remember correctly, but it was 1991. And the film got green-lit for production, I guess it would've been in '96 and produced in '97 and released in '98, something like that.

Randall Jahnson, writer: I met with Steven on — I wrote some days down — May 31, 1991. So this was a good seven years earlier from when the movie was released. [...] You don't get to meet Spielberg right away. You have to sort of go through channels. So I went out to Amblin a couple of times and met with their development staff, and I'd really like to recognize the two women that were heading his development project at that time: It was Kathy Stewart and then Deb or Deborah Neumeyer were there. So I met them first and they had read some of my work. So they said, "Hey, listen, we're really interested in you. Steven wants to set it during the California Gold Rush. How do you feel about that?" And I said, "I love that because I'm a big history buff, and especially Western history." And I said, "I think that's really an interesting concept." And they said, "Okay, great." [...]

Randall Jahnson, writer: I was given the green light to meet Spielberg. So that came on May 31, 1991. So I got the call and it's like, "Okay, you're going to meet him. He wants to meet you, but it's not going to be at Amblin. It's going to be at MGM where he is shooting 'Hook'. So he wants you to come down and meet him at his trailer down there." And I go, "Oh, okay. All right. Well, that's pretty cool." So I went down and was ushered by one of his handlers, gofers, down to the trailer and they said, "He'll be here in just a few minutes." So I was waiting around and then boom, the door flies open and in comes Steven. And he's just as charming and boyish as you can really imagine, very enthusiastic and stuff. "Hey, how are you?" And just immediately gets right down to it.

He said, "I haven't seen 'The Doors' yet. I'm really kind of square when it comes to rock and roll and stuff, but I don't know, I've heard you might be the right guy for Zorro. So what do you think?" And I said, "Well, I'm really interested, for the same reason — I love California history, love Western history." I said, "If anything, I would be interested in making Zorro more ethnic, making him more brown-skinned, more of a traditional Mexican/Latino character." I knew that Johnston McCulley, who had created the Zorro character, had been a journalist and kind of an amateur historian. I knew that he was very conversant in California history, and he no doubt drew from Joaquin Murrieta and Tiburcio Vásquez, who were famous, storied, Robin Hood-like characters from the Gold Rush period. I said I would like to go back to those roots and get away from the Guy Williams, the real Anglo-looking guy from the old Zorro TV series and stuff.

Spielberg said, "Yeah, yeah, yeah, that's great. That's great. It's really cool." He said, "I would love that. I want this whole thing to read like a history lesson. I want the Bear Flag Revolt. I want Joaquin Murrieta, I want the beginning of statehood, the Mexican War," all this kind of stuff. And I was like, "Okay. Whoa, that's a big canvas, but sure." We were very excited about it. Our conversation was — we had only [gotten] about 10, 15 minutes into it when somebody came in and said, "Steven, they want you back on the set." So he said, "Oh, okay, look, just wait here. If I'm not back in 10 minutes," he said, "just come on down to the set and we'll continue the conversation there." And I was like, "Really?" And off he goes. And I said, "Please God, make him not come back to the trailer." So a few minutes later, the handler came back and said, "He wants you down on the set." I said, "Okay."

I remember this so vividly ... I remember going out the door and coming out, and coming up is George Lucas and Carrie Fisher. I remember Lucas just looking at me and saying, "Hey, is Steven in there?" And I said, "No, he's down on the set. Come on, follow me!" [laughs] Oh my God. Never met before. So yeah, it was something I can't believe. Already this day is something I'll never forget.

So we go on down, and he was shooting in the old sound stage where "The Wizard of Oz" was shot. I forget if it was Stage 2 or 3, but it was one of the great, storied, ginormous facilities. And we came in and it was unbelievable, the set. He had the whole ship there, the lagoon, and literally a cast of dozens, if not hundreds, of extras — pirates and villagers.

The camera rig was set up in the stern, so we weaved back through that. And there's Steven there, and Kathleen Kennedy was there. She was still a mainstay at Amblin that time. And she was very sweet, very nice. She'd said she'd read some of my stuff and thought it was really good. "We're really happy to have you." Just really, really welcoming. And Spielberg then just ... everybody in the crew was moving around and setting up the next shot, and he said, "Oh, here, meet Robin Williams." And everyone comes over and there's Robin Williams, who seemed to be very preoccupied. I saw him kind of talking to himself. I think he was going over lines to himself there.

And then Dustin Hoffman, "Oh, Dustin, come over here and meet Randall. He's a writer." He didn't break character. He was completely in costume and he put out his hook to shake my hand, which I had a hat on, and I bowed and genuflected as well. And I said, "I think your reputation precedes you, my Lord," something like that. And he goes, "Argh." [laughs] But it was pretty funny.

So then Steven just started going right into it again. "So what do you think about the Bear Flag Revolt and this and that?" And I said, "Well, all that stuff is really, really cool. We just want to have a story that fits all this stuff. It's a big canvas." He's like, "Yeah, yeah, I know. I just get really excited."

I remember this very distinctly: He said, "Apart from I want it to read a history lesson," he said, "don't worry about the action. Just give me a great story with great characters and don't worry about the action too much, okay?" "Okay, you're the man." And then [he'd raise a] finger. "Hold on just a second." And they would do a take and he would cut and then turn around to me and just pick up right exactly where we left off. It was pretty astonishing. I'd never seen anything like it. And this went on for 20 minutes or more, where they're doing that setup there. I'd never seen anyone compartmentalize like that. And it wasn't like he's a machine. It wasn't like he was sort of robotic or doing things by rote at all. I mean, he knew what he was doing for the direction, but he turned around, he looked me in the eye. It was a meaningful conversation. He was taking in everything that I was having to say about it, and I felt it was landing. So it was pretty astonishing. It was a great day.

Chapter 2: Pitching Spielberg

Randall Jahnson, writer: So he turned me loose and word came back I had the job. So that's good news and bad news, in a sense. The good news is you're working for Spielberg. The bad news is you've got to come up with a story now actually, because they really didn't have a story. They were totally open to new ideas. They wanted to bring fresh blood to the Zorro franchise.

Once that initial exhilaration was gone and the deal was being negotiated, I was going, "Oh God, oh man, what is the story?" So I had to go out and actually pitch to him. Before I committed to doing any kind of writing whatsoever, I had to go out and pitch the story verbally to him. And I went out twice. And both times he was underwhelmed. He said, "Yeah, I'm just not hearing something that feels fresh to me." It just didn't feel like it was something that he wanted to do. And I started getting pretty nervous at that point. They don't tell you, but it's pretty much third time at bat, and if you don't hit it out of the park at that point, you're kind of, "Thanks, but no thanks." It's onto the next.

I was scared, frankly. I was really scared, because the issue for me was that I was trying to give him what he wanted, which is set during the California Gold Rush. But the California Gold Rush, gold was discovered in 1848, and then the rush started in 1849 and then into the 1850s. The Bear Flag Revolt was slightly before that time. So California was essentially sort of independent, and then statehood came in right on the tails of the Gold Rush, of course. So to have Zorro be Zorro as kind of the wise and crafty Don, well, most of those guys were gone. Their lands had been taken from them. So we were talking about two different eras. In other words, Zorro couldn't be Zorro, to own the great rancho. The halcyon days of California? Those days were gone. Now it was different, and I just had a hard time reconciling the history with what Spielberg wanted.

I swear it was not until the night before that I had to go out and meet with him that it came to me, finally. And it's just like, duh, there's two of them. Of course! There's two of them, and it's about passing the torch. It's about what happens when you're kind of a superhero, for lack of a better term, and you're just getting too damn old to do it anymore? And that's where it just suddenly clicked. So I rapidly came together with this scenario of where, at the very beginning, we'll see the original Zorro in Mexican or Spanish California in all his glory, saving a group of campesinos from a firing squad for stealing loaves of bread or something like that. And then I thought, Oh, Joaquin. We could have little Joaquin be an orphan! It just started magically coming together.

I was literally still making it up as I was driving out to Universal. I'd gone to UCLA film school, so I was living still on the West side of L.A. at that time. So it was a long drive out there to Amblin, so I had some time still to keep making it up and talking to myself and pitching it to myself in the car.

I got out there and ushered into his office, and he sits down on the couch and it's like [crossing his arms], "So what do you got?" And I think he was not expecting me to ... maybe I was going to whiff again.

So I started pitching this thing with the opening and there's going to be a firing squad and this and that, and then Zorro comes and saves the day. And we have these two orphan boys running around in the midst of the interaction, and they see him and they talk ... he is a real life hero to them. And I remember it was just like ... when he gets something, I mean he listens, and then as soon as he gets the beat, he'll just go, "Yes," and nod. And that's code for just, "Got it. Move on to the next thing." So I started getting, "Yes, yes, yes." And then at one point I think, Oh my God, I got him on the line. I've just got to reel it in. And I kept imagining, I kept hearing the ringing of a pinball machine as I was scoring points: ding ding ding, ding ding ding.

Randall Jahnson, writer: I carried on through this whole thing of at the very, very beginning, and he saves the boys and he gives a young Joaquin the medallion and he said, "Thank you. You saved my life. I will always remember you." And then he rides off, and the image was a classic image of him rearing on Tornado against the setting sun and waving, and then [going] down. But I said we switch angles from that to when he comes down and he slumps in the saddle. And we didn't know, but in this fight, he had gotten wounded and he was bleeding badly. So we follow him back to his rancho, and we go through kind of a hiding place, but he goes back to the rancho and he's bleeding and needs help. So his loyal assistant takes him, summons a doctor, but the doctor is not a good guy and figures out who he is and uses that as a means to turn him in and advance his career, so to speak.

It ended with the old Zorro being dragged away by authorities. And his infant daughter, or very young daughter, was screaming for him. He did not have a wife. He was a widower, as I recall. That was a big difference there. So anyway, he's dragged away, and boom, we cut to 20 years later. And we're now with Joaquin Murrieta, and we ultimately see him robbing some guys, he and Three-Fingered Jack or whatever, and he's in the midst of a robbery. And in the course of it, we see this medallion around his chest. And we thought, "Oh wow, Joaquin's a juvenile delinquent now." I mean, he's grown up, he's a badass guy and everything. And what has happened in those 20 years is the Gold Rush has happened. California and the beautiful halcyon days of California, those are gone. And now California's just been run over by stuff.

We see him make a robbery, but then Captain Harry Love and the California Rangers come after him and in a run and gun battle, his brother is killed, and Joaquin barely gets away and Three-Fingered Jack barely gets away or whatever. And he's destitute and finds himself hiding out in the ruins of the old rancho. And that's when the old Zorro shows up and he is teetering around, and then Joaquin's going to try to steal his horse, and the old man is very good. And then he sees the medallion on him and he says, "Where did you get that?" And anyway, that set it up. I carried it a little bit forward, but basically that was the setup. They realized they had a common enemy ...

All the rest was going to be invented, but I just felt like if I could just get him hooked on that, and I finished at that point and just kind of quickly just summed it up and Spielberg just jumped up. He said, "I love it. I love it. I love it." He said, "This is great." He's like a 12-year-old kid jumping around there or whatever. And he said, "Do you think we can get Sean Connery to play the old guy, the old Zorro?"

Then the pressure was on to really make all this stuff work. So I delivered four drafts for them ... there were nine writers on it in all. I think there were 32 or 50 drafts of it when it was all said and done. I remember standing next to all of [the scripts] at one point that had been given to me by the Writer's Guild to help determine credit, and it was just pretty astonishing. [...]

Terry Rossio, writer: The first thing that comes to mind when I think about "Zorro" was the moment when I first became aware of the project. [My writing partner, Ted Elliott, and I] were just starting out in the film industry and back then, the internet wasn't a thing, so it was very difficult to get information. You had the trades, Variety and Hollywood Reporter, but that was pretty much it. There was nothing available "behind the scenes."

Except for one source. There was an obscure magazine called Film Journal, targeted to distributors, and once a year they would publish an insert called The Blue Pages. Why they did this, I have no idea, but the Blue Pages would detail every project in development at every studio, hundreds of projects. I remember coming to the end of the list one year — projects were arranged in alphabetical order — and there was Zorro, to be made by Steven Spielberg!

My mind was ablaze. A Zorro film made by Spielberg? How cool would that be? And at the same time, there I was, sitting in my rented room with three roommates in an apartment on Balboa Island down in Orange County and thinking, how in the world could somebody ever get a job like that? It seemed impossible — as far away as walking on Mars.

So several years later, it was so incredibly strange to get a meeting to pitch on the project. It was an "open writing assignment," so the process was, you get a call from your agent, you schedule a meeting, and go in and pitch your "take" to the executives, in competition with other writers.

We had a particular approach: Explore the adventures of Don Diego de la Vega in Spain, as a set-up to his return to California, where he would continue to face off against a rival and continue a love triangle romance. As far as we knew, this hadn't been done before. We also had the element of a villain attempting to buy California from the United States using gold he'd secretly found in California.

Spielberg must have liked something we said, but he came back with his own structure — he wanted a "passing the torch" of Zorro to one of the Murietta brothers. So we adapted our story to his structure for a second pitch, and that became essentially the shape of the film that was made. All in all, as I recall, the whole process was a whirlwind two or three weeks.

Randall Jahnson, writer: When ultimately I met Rossio and Elliott at a Writer's Guild function and we started comparing notes, they go, "You came up with the old Zorro/young Zorro thing?" And I said, "Yeah, that was me." And he said, "Oh, wow." I said, "You guys didn't know that?" "No, we always thought Spielberg, it was his idea." "No, no man. That's why I'm sharing credit with you guys."

John Gertz, co-producer: I guess we were being naive at the time. Well, I think we all were. [Spielberg] said he was going to direct it, but once the deals were signed and so forth, it became apparent that really, he was not going to be directing it.

Chapter 3: Mikael Salomon

In 1993, cinematographer-turned-director Mikael Salomon was hired as the director of "The Mask of Zorro."

Mikael Salomon, director: I took over a [film] for Disney, and Steven Spielberg was the producer on it — not [officially], I think, but he was the one who came to me, because the movie I ended up doing was "A Far Off Place" with Reese Witherspoon. And it was a project I always kind of liked, and I was a DP. And I said to Kathy Kennedy, who produced several things that I was involved in as a DP, "If it ever gets around to that, I'd love to be involved."

They gave it to a French director, "A Far Off Place," and Frank Marshall offered me [the DP job on the Andes Mountains plane crash survival film] "Alive," because, "You've done sand, you've done water, you've done heat, you've done, how about some snow?" I said, "Snow? No thanks." I've done my snow, because I'm from Scandinavia. [I've done] I don't know how many shows in the snow. And also I wanted to start looking for a project to direct.

So one day, Kathy Kennedy calls me from the glacier up in Canada where they were shooting "Alive" and said, "Can you call Steven? They have some problems on another movie." "Oh, I know that one," I said, "you gave me the script a long time ago to read." "Call him." So I ended up doing ["A Far Off Place"]. Steven really liked it. That's the short story. And he said, "You're going to do 'Zorro.'" I said, "Yes, sir, I'd love to."

Here's the unverified version, because my memory is not that great, but Branko Lustig became the producer ... he was the producer on "Gladiator." He did "Schindler's List" with Steven. So I said, "Yeah, can't do better than that." So he and I produced a budget. We went to TriStar and said, "Here's the numbers." I can't remember the numbers we came up with, I think it was 45 million dollars. And they said, "That's too much money. We will spend 35 million dollars. That's it." So we went back to the drawing board, and this took — I was shooting commercials at the time, and we worked on the budget again. Months went by, we go out to TriStar again, and we said, "45 million dollars." Again, they said, "No, no, we can't do that." And it kind of ended in a stalemate. We said, "We can't do it for less than that." So at one point I said to Steven, "Steven, I need to entertain other offers, and I love the fact that [you're working on this], but this has been going on for two years or something like that." And he said, "Go with God. That's fine, and we'll do something [else together]."

And then I think Robert Rodriguez got involved, and as I heard — this is only hearsay — exactly the same thing happened. He said, "This can't be done for under 45." So Martin Campbell came up and said, "I can do this for 35 million dollars." And they said, "Okay, you got the job." And I think the movie cost 50 million. [laughs] [Editor's note: The final reported budget ended up being $95 million.] So I learned a lesson, a very serious lesson about that. And it's not a good lesson, really: That you should lie, lie, lie, even though you know what the facts are.

Mikael Salomon, director: Viggo Mortenson, I remember, read for or had a meeting for the sheriff, I think it was. Sean Connery was involved at one time [as Diego de la Vega]. Steven said, "No problem with him. I'll take care of him. He could be a little grouchy, but I'll be there with you." Who else was [in the mix]? Some big — oh yeah, Tom Cruise. Early on, [Spielberg] wanted to offer it to him. Have you heard that? He wanted to offer it to Tom Cruise. And my friend and countryman Bille August had done "The House of the Spirits" with all non-Latinos, and he got in so much hot water because of that, and they picketed the movie in South America. And I said to Steven, "You know, that's probably not a good idea, just for that reason." This is unverified. But apparently he offered it to Tom, because one day I was doing a commercial and my assistant said, "Mikael, there's Tom Cruise on the phone for you." "Tom Cruise? Okay." I had worked with him on "Far and Away." I was the DP on "Far and Away." So he called me up and said, "Thanks for the offer, but I think it's not a great idea for me to do this movie because, as you know..." I said, "Tom, you're a very smart guy. Absolutely, you're absolutely right." [...]

The guy I wanted ... Andy Garcia was the one who, I was talking to him, we had great meetings, but then it all petered out. It became Antonio Banderas. I thought it was a great movie, but it wasn't the movie that I envisioned originally. [...]

We hadn't hired a production designer or anybody like that. And usually, I like to do storyboards, but it was still all in the deal-making. And to be honest, I was busy, and I loved the idea of the project, obviously, with these guys involved, Branko and Steven, so there's not much to think about here. But I didn't really get into it. I know I was talking to, [Spielberg's longtime editor] Michael Kahn was going to edit it. He had agreed to edit it, and I think [Spielberg's now-frequent collaborator] Janusz [Kamiński] was interested in shooting it ... he was definitely around, because I remember when I was working with Steven as a DP, I actually visited him in Krakow where he was [filming] the first project he did, "Schindler's List," with Janusz. That was obviously before this.

Chapter 4: Robert Rodriguez

By 1995, Salomon had left and the project had a new director.

John Gertz, co-producer: So the director that [Spielberg] then brought on board was Robert Rodriguez.

Doug Claybourne, producer: We went out and scattered locations and we took Robert out to see them and he approved the locations, but I never really got a chance to speak creatively. I mean, I was basically overseeing the production of the picture, but Steven and two development producers were working with Robert in terms of the creative vision for the picture. He had worked with [production designer] Cecilia [Montiel] before, so she and Robert were completely in sync. And then ultimately Cecilia stepped into the movie with Martin [Campbell]. But I don't know how different [Rodriguez's] vision was of the picture to Martin's. I don't honestly know that. He was a quiet kind of character as well, so it was a little more difficult to get to know him.

John Gertz, co-producer: I took a creative meeting with Robert. I'm working with him now on a different project, on a Zorro TV series. But at that time, he was a young creative star guy, and he gave me his great vision. The part that stands out is when he says, "And then Zorro's going to lop off the villain's head, and it's going to go bouncing down the stairs, bloop, bloop, bloop, down the stairs!" And I'm thinking, "Zorro lopping off heads?" [laughs] I'm going, "Oh, no!"

Terry Rossio, writer: I recall a production meeting with Robert, also his wife Elizabeth Avellán as producer, and the production company and studio. This was around the time Robert was finishing post-production on "From Dusk to Dawn." Later, we had a meeting at Robert's house, and I was super impressed that he had a nonlinear video editing system set up in his living room. At the time, to have your own editing system was kind of a big deal. Those gig drives cost tens of thousands of dollars! But it was all in keeping with Robert's style of filmmaking, which was to do everything himself, hands-on, on his own.

John Gertz, co-producer: All I know is that eventually what happened was on a Friday afternoon, he was the director. On some weekend, he had meetings with Spielberg, and by Monday morning, he was out. What happened and why? I never got the straight story to my satisfaction of what that was. It would be hearsay anyway, but it would be fascinating if you could figure out what happened in the room between Spielberg and Robert Rodriguez that got him bumped.

Ray Zimmerman, physical production executive: It was early in my career. I started at Sony in 1995 and did "Mask of Zorro" in '97. It was just such an interesting time in the business, but it was also, for me, just being new in that job, it was a real big job. And I was working probably like 15-hour days for about the first year and a half or so, and I was just kind of getting into my rhythm and kind of understanding what the job was about when "Zorro" came along. [...]

So all of a sudden I'm called into this one meeting. And it's Spielberg and Laurie and Walter — [executive producers] Walter Parkes, Laurie MacDonald — and then Elizabeth Avellán, and the director was Robert Rodriguez. And then there was all the studio people. It was Stacey Snider, Marc Platt, the co-presidents, Gary Martin, the president of physical production for the whole deal. He was my direct boss. We all thought it would kind of be a rah-rah kind of event.

I get there and we sit down, and there's Robert at one end and everybody else is kind of down at the other. And Steven starts talking about the script and the structure and kind of his philosophy, as he does, which is great. It's always great to hear the wise man talk. And he turns to Rob, then he brings up the thing about the budget. And I think the budget, it was at that time around, as I recall, around like 35 [million dollars] or something like that. And Steven says, "Well, we have to get the budget down, but I'll help you. Don't worry, I'll help do that."

And Robert took umbrage. There was clearly some other stuff going on before the meeting had happened, but he took umbrage for this. And he stood up and said, "Look, I'm not interested in cutting the budget. In fact, we need more. I think we need more, like 40 million." And Spielberg had this script and he just went bam, and slammed it shut. And he looked at Robert, and Robert just walked out of the room. Holy s***. So it's like, "Ray, welcome to the film business."

Now Elizabeth was Robert's wife and she was [going to be] a producer of the movie, and I'd known her. Actually, my wife had worked with Robert on "Desperado." And so I had a relationship, a personal relationship, with him on that. So after the meeting, Elizabeth comes out of my office [and said], "What are we going to do?" I go, "Just chill out. We're going to find out." Cut to: They already had Martin Campbell in the wings.

Chapter 5: Martin Campbell

At that time, Campbell was hot in Hollywood after directing "GoldenEye," which rejuvenated the James Bond franchise.

John Eskow, writer: I had written, at that point, three or four Westerns. I was kind of known as a guy who was good at Westerns. I love Westerns and I had written one recently for Fox, which was a very different take on the story of the Alamo. As a result of that, I got a call from an executive at TriStar saying, "We have a project that I'm sort of asking for your help on." And that was not "The Mask of Zorro." That was a script that was, at that point, 30 or 40 years old. It had originally been meant to star Steve McQueen. That's how old it was ... so I got this call from TriStar and they said, "Martin Campbell," who at that point was just really taking off as a really super hot director, "has read this, and he wants it to be his next movie." [...]

[So] every morning at eight o'clock, I'd get up, leave my hotel and drive over to the Fox lot, which was where Martin's office was. And there was nobody else on the freaking lot. It was just basically me and him, because everybody was on vacation [in August], but we were having a great time working on this other Western. But all of a sudden, with a great air of mystery, Martin would disappear for four hours at a time, leaving me alone on this sweltering empty lot.

Finally, it happened so many times, that I got a little mischievous, and I poked around in his desk and I saw a script for a movie called "The Mask of Zorro." And I flipped through it a little, but it didn't appeal to me at that point. I was really all-in on this other Western.

So one day, he came back from a four-hour meeting, and I said, "Martin, I got a confession to make. I peeked at your desk and I know about this movie that's in development, 'The Mask of Zorro.' And if you feel that you have to leave this project to go do that, I will understand and hopefully we will revisit this movie. But just one thing that you ought to know is, don't ask me to rewrite this one. I'm not interested."

Needless to say, 48 hours later, I was signing contracts to rewrite this one after having made my grand proclamation. And we put the other one aside and unfortunately never got back to it. It would've been a great movie. So we just flipped over from "Running the Big Wild Red," it was called, to working around the clock on "Mask of Zorro." Because the situation at that point was really intense and pressured.

We were told that Antonio and Hopkins had problems with the current draft. I saw the potential riches, let's say, that were there. And Rossio and Elliott are very good on plot, they're excellent at that, but it was really felt that the script needed a radical rethink — "fresh eyes," as they say. So I was the fresh eyes. And because Martin and I had set up this wonderful work rhythm on the earlier Western, we hit the ground running on "Mask of Zorro." I wrote it really quickly ... And also surprisingly quickly, word came back that the studio really liked it, that Banderas and Hopkins really liked it, and it was a go movie. It hadn't been greenlit yet.

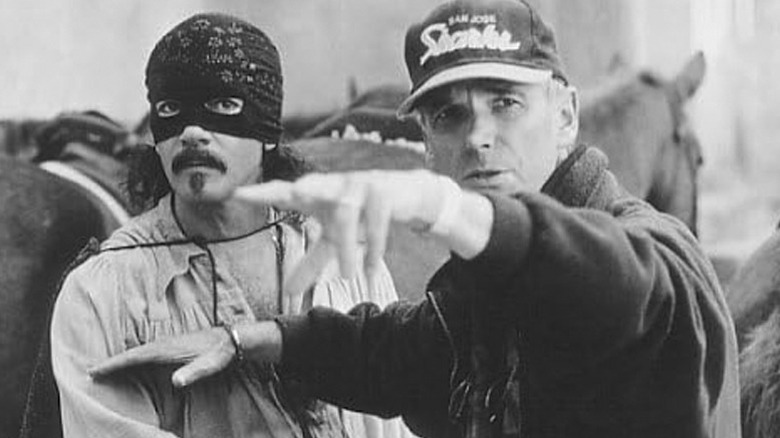

George Parra, first assistant director: Martin Campbell is probably one of the most prolific directors there is. He can direct anything. I mean, he resurrected the Bond series, and he's just a craftsman director. He directed a lot of great films, so it was a pleasure to work with him. And we had a lot of good times and laughs. So I mean, the overall experience was a giant adventure. From the beginning to the end, there was so much going on.

Thom Noble, editor: He is the hardest working director ever. He never stops. Never, never, never. It's just on and on and on. He's absolutely the most enthusiastic, the most on top of it guy I've ever come across.

Doug Claybourne, producer: [My biggest challenge] was get getting through the transition between going from a director that walks off the show because he's not happy to a new director that I didn't know. I mean, I knew his movies, but then transitioning from that to literally, I had hundreds of people on the show starting and I had to let everybody go. And then find out, "Well, what's Martin going to want? What's he going to like?" We took him on a location scout. Am I going to be on the show? Who knew? I had no idea if we'd get along. And then who are we going to be able to hire back if, in fact, I'm involved at all? So I think that was the biggest challenge for me in the movie. It was just making the transition work if it was going to work at all. And then what's the difference? What's the movie? How are we going to save the movie and still make it a good movie?

Chapter 6: Pre-production

With Campbell on board, pre-production ramped back up as the film raced toward its start date.

Doug Claybourne, producer: We had prepped 20 weeks with the whole crew, and then we started all over again with Martin and prepped yet another 20 weeks. And Martin ended up basically hiring substantially about 90% of the crew that we had on board already. I mean, the same production designer, I ended up staying on as one of the producers, and about 90% of the locations he liked that we had chosen.

But then he went back through and really prepped the movie himself, made changes. That's when Anthony Hopkins came on. So it was a huge prep on the movie. It took a long time to get it set up. [He was] very focused on his prep. He came in early every morning, an hour or so early, to work out his shots for the day. Very prepared. He was probably one of the most prepared directors I've ever worked with. And lovely to work with. He was a real gentleman.

John Eskow, writer: I wrote, I think two or three drafts as this was all coalescing, and now locations are being scouted. And I'm writing a lot of drafts, getting a lot of notes from Spielberg and from Walter Parkes and Laurie MacDonald. It seemed like we were all in complete agreement, but there was one issue that we weren't, it turns out, in complete agreement on. And that was they wanted — or at least Spielberg wanted — for the dialogue to be very period, sort of flowery, 19th century-sounding, a lot of which you hear in the movie as it stands. I didn't want that. I wanted less of that. And frankly, that's my one only serious problem with the eventual movie that we produced. And it's not a big deal, it's just how I feel. The point I kept trying to make was in writing period movies — and I had written a lot of them — it's important to remember that people back then didn't know they were talking period, flowery ... it's just how they might have talked. So you have to find analogous ways of human speech. You don't want to be writing a movie about a troubled prince in the present-day and have it be Hamlet doing Shakespeare.

So as the summer turned into fall and the start date approached of shooting, I kind of made my disagreements known, and I think I probably did that too forcefully. I mean, I was passionate about the movie. I loved the movie by this point, and there used to be, and I forget who said it, but a line from Shakespeare, I think, "He loved, not wisely, but too much." I loved it, not wisely. I fought a little too hard. And I forgot the first rule of being a screenwriter, which is that you're not the boss. And I think I trusted my passion for getting it right would immunize me against friction with the producers. I think I thought that all the way up until the day when Martin Campbell called me up and said they were getting another writer.

They felt the movie was locked-in at that point, but they wanted someone who, number one, was available to go down to Mexico on location to shoot, which I was not, and two, was on board with the what I would call flowery dialogue concept. Having said that, it doesn't seem to have bothered a lot of people, the flowery dialogue thing. So who's right, who's wrong? It's all silly at this point. It's water under the bridge, because going back to Rossio and Elliott, with their excellent plotting and their interesting little twists that they programmed into the story, going then through me giving it a more modern, I think what people said at the time was hipper, more hip character in Banderas.

I added a lot of things like Captain Jack forcing them to sing, Banderas and [his brother] when he is leading them through the desert, which people love, I have to say. That just gave the movie a fresher, funnier sensibility. I think my favorite contribution to the whole movie, we were also watching a lot of Sergio Leone Westerns, Martin and I. And I wanted to somehow program into the opening a Sergio Leone moment.

Rossio and Elliott had written the opener, the execution, which of course has been in a lot of movies, but always works. And so suddenly, I just sat up in bed in the middle of the night and I had what I wanted, which was the image of the kids cutting the eye holes in the wanted poster and looking out, having that image, it was as if you were saying to the audience, "You are going to be seeing the movie through these eye holes of these kids." Several levels of playfulness there. We just relentlessly went through the script, adding bits of business, simplifying certain overly-plotted things, but very much fueled by what Rossio and Elliott had started. They came in after Jahnson. So I guess I should say what Jahnson and Rossio and Elliott had done.

Terry Rossio, writer: One interesting moment came during rewrites in pre-production. Anthony Hopkins had read the screenplay, and told us, "There's a scene missing." Hopkins pointed out there was not a scene where Diego de la Vega got to speak with his daughter Elena alone, one on one, with him not able to reveal the truth. "It's like two ends of a triangle haven't been connected," he said, and he was right. That led to us writing another scene in the stable, the one where the horse is groomed. Diego and Elena are able to connect as adults on an emotional level, and of course it's an absolutely necessary scene.

George Parra, first assistant director: Pre-production was long and wonderful. There were lots of pre-planning and a lot of horseback riding lessons and sword fighting lessons and choreography and scouting. And it took months to prep that film, and Martin does it properly. So it took a lot of time, and the studio gave us the money to do it.

Doug Claybourne, producer: Mexico had a couple of trade unions at that point. They covered the below the line crew and we needed to make some kind of deals with them for their work on the show, because we wanted to be covered by the trade unions that represented the local grips, electrics, carpenters, et cetera. And those were kind of tricky deals to make, and I worked through my local production manager to negotiate those deals. And at a couple of points, it got a little sticky with the trade unions, and as I recall, there was some kind of negotiation that — and I have to be honest with you, I don't remember exactly the details — but they either wanted more money than we could afford or they wanted to hold back on services.

And at some point, I remember that I let everybody go. I literally fired the entire crew, basically as a negotiation — I don't want to say "ploy," because we were serious. Based on the rates that they were talking about, we couldn't proceed. Because we were going to hire hundreds of people to do construction, grip, electric. We were all over Mexico. I think we were in 25, 30 locations. So I mean, we had to let everybody know that we were serious about it, and we pulled the plug and moved the production. So I think by doing that, we certainly convinced everybody that we were serious, that we needed some kind of concessions. We got the concessions we needed in order to move forward. But they were all good faith negotiations. Nobody was angry at one another. It was a matter of both sides having to say, "Hey, we're serious about this and we need help to get it done."

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: The deal at the time in Mexico was that for every foreigner that we brought into Mexico for the shoot, we had to hire a local. So I had to have equal numbers of local Mexican coordinators for our team, and they were in charge of our local accommodations and translating the scripts into Spanish for the other people. And it was never love at first sight between us and the locals because they basically got paid better than us, barely worked, hated us. [...]

I just remember that Christmas before we started shooting in Mexico City, I got a call from one of the other coordinators, Nelson, who tested me to see if I spoke Spanish properly and if I qualified to come and be there on location. [...]

The whole flight there, I kept thinking, What have I done? What have I done? Yeah, I speak Spanish, but I don't speak production Spanish, which you realize is a whole 'nother language. Even in English, it's a whole 'nother language. To tell a local [production assistant] to go get something done in production lingo is a different language that I was like, "Oh, God. I've made a horrible mistake because I don't know how to say, 'Quick, get the Xerox 500 times on this color paper, three hole punch it, collate it, staple it, and distribute it to this list.'" That whole thing was a massive learning curve of even how you say "staple."

And all of our rented desktop Apple computers were top of the line, but internet wasn't really a thing yet, and we didn't have cell phones, and the only way we communicated with the outside world for seven months was that we had two satellite phones that literally looked like that James Bond suitcase with a satellite that they stuck on top of the production trailer on set. And then one was with the exec producer. But we didn't have one in the office. We had to rely on whatever the local thing was.

Phil Meheux, director of photography: [Martin and I] found that we got on very well, and I ended up doing nine films with him. It got to a point where I sort of knew what he wanted, and we agreed on so many things.

I'd put the viewfinder up and say, "I was thinking about something like that," and he'd go, "That's it. Perfect. Yeah. Yeah." ... It got to a point where he didn't really tell me anything. He'd show me the script, and he wouldn't say anything about the look of the film or how he saw the film. He left it to me, which I also obviously enjoyed immensely, which gave me a great deal of responsibility at the same time.

But when "The Mask of Zorro" came around, which was 1997, we'd already done James Bond "GoldenEye" with Pierce Brosnan, and I did another picture after that called "The Saint" with Val Kilmer, which wasn't very successful for various reasons. Then, up came "The Mask of Zorro." So all Martin did was ring up and say, "We're doing another one. We're going to start in so-and-so, so-and-so. I'll send you the script." I read it and I thought, What do I do with this to give it some sort of interest? I'm making it sound all grand now, because it was just, it was your job. You know? You just had to think about how you did things, how you planned it.

I had this idea that, because it was costume and it was a sort of a comedy action film, but at the same time, the action was very real, but there was comedy and glamour in it with Catherine Zeta-Jones and all of that, I decided it should look like an old Technicolor film. So that was my thesis, is to make this look like old Technicolor with plenty of color, as often you could make it, but at the same time, keeping a certain reality to it, which is a difficult line to keep with. But that's really how I came upon that approach, as it were.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: We had a lot of stuff for two weeks sitting on the border of Mexico in L.A. All of our big trucks with our armory, and with our horses, and with our set [decorations], and literally anything we needed that was being brought in from the U.S. had been sitting at the border for two weeks solid. But Sony TriStar had decided at the outset that we weren't going to bribe anybody. This was going to be a company policy.

Literally the day before we start to do pre-pro shooting and camera tests, we had one of our team go out there with stacks of American cash and just make it rain on the border, and suddenly all the trucks were coming in. So it started rough where it was a scramble to get into pre-production, because people were only just arriving who should have been there two weeks prior to start unloading, and start taking stock, and doing some of that rehearsal pre-camera testing. It was intense from day one, and bribing started from day one because it's the only way to do business down there ...

We were behind schedule by two weeks from the very beginning, and I think we were told we were going to be on location five to six months, and that we had to pack one bag but have enough clothing from, well, all these different locations, different temperatures, but from January to end of summer. So that was a big thing for everybody — how to pack a whole year's worth of stuff in one bag.

Chapter 7: The cast

Antonio Banderas had starred in dozens of films in Spain and appeared in a handful of English-language productions, but "The Mask of Zorro" launched him to superstardom in the United States. Anthony Hopkins had just starred in "The Edge" and was filming Steven Spielberg's "Amistad" concurrently with this production. Catherine Zeta-Jones had played a supporting role in "The Phantom," but legend has it Steven Spielberg saw her in a 1996 CBS miniseries called "Titanic" and brought her in to audition for this film, which changed her career forever.

George Parra, first assistant director: I mean, Antonio's a pleasure. He became one of my great friends, and I AD'd for him shortly thereafter on a film that he directed, and to this day is still a good friend of mine. He's a cool cucumber. He's a talented actor — always was, always will be. He's gifted. He's very coordinated. He can ride a horse. The sword fighting came easy to him. He did a lot of the stunts, but not all of them, of course. But he's talented, charming, super handsome, just a pleasure to work with.

John Gertz, co-producer: I mean, his Zorro was probably the best that's ever been performed.

Glenn Randall Jr., stunt coordinator/2nd unit director: Banderas was great to work with. He came and worked with us on the second unit on the chase scene, and he was really enthusiastic and game for almost anything I asked him to do and kept making the remark that he said, "I want this to be good, Glenn. I want my kids to be proud of it. I can't wait for my kids to see this."

John Gertz, co-producer: Banderas was really an artist. I mean, he cared so deeply about every element of the production. Fortunately, Martin was not at all thick-skinned, but Banderas was almost directing the director. And in a positive way. I mean, they seemed to have had a positive rapport, but Banderas would constantly second-guess every element of the production and scrutinize it, and in between shots, come and look at his takes to see how he could improve himself. He had really a master's dedication to his art.

Thom Noble, editor: The villains were so good, as well. When you have a really good villain, you're home free.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: The guy who plays Montero, [Stuart Wilson], he was very particular about his character's little curly hair bits and was constantly making sure they were just so with a certain amount of wax and that they looked just so. He was kind of driving hair and makeup crazy. And one of the bats that they released [in the dungeon scene] had got in his hair and was messing it up just before the shot, and he was screaming for help. And hair and makeup were both like, "He's all yours. We don't do bats."

Phil Meheux, director of photography: Montero, he ended up in another film we did called "No Escape," which was shot in Australia, because we liked him so much. He was very professional actor. He always knew his lines, knew where to stand. He could make it exciting, the performance. When you're doing a film like that, it's got to have excitement, and the whole point of staging anything, you've got to — it's show business. I always use this word. It's show business. There's two people dancing [in a scene]. All right, but what can we do with the camera or the lights that makes it more show business-y, that makes people can't turn their eyes off the screen?

John Gertz, co-producer: Zeta-Jones, of course, was a revelation. Spielberg had discovered her, just watching TV one night. He saw her on TV and said, "I've got to have her for that role." And that was just magnificent casting, of course ... I often sat next to her on the set, talking about the weather or whatever, but not realizing at the time when a mega-star she was about to turn into. But I found her to be very thoughtful and with apparent depth beyond what you would just see as a pretty face.

Phil Meheux, director of photography: I used to say to Catherine a lot, I'd say, "When you look to your left, don't just use your head, because it makes these big stretch marks on your neck." So I'd say, "Turn your body slightly as you look to your left," and she'd say, "Oh. Got it." She was always good like that. I remember on one occasion, she said to me — we shot, we rolled, and we cut, and Catherine said, "Was I on my mark?" I said, "Yes, you were." She said, "Oh, because the light didn't feel quite right." I went, "Oh. Interesting." So I started to look behind me, and there was one lamp, and the bulb had gone. Nobody had noticed at that particular moment in time, because we're all caught up in the action and everything. But she knew what she was doing.

John Eskow, writer: When I came on board, they were basically decided on Cameron Diaz, oddly enough, but she would've been, at that point, I think, good for it. She's got a lot of Hispanic blood in her, and she was of course, at that point, really sexy. And the role called for both sexuality, kind of innocent sexuality, and real tough, sassy, strong woman. Which I think is another thing, by the way, that makes the movie work so well, is that at a time when there weren't very many strong women in movies, that was one.

Ray Zimmerman, physical production executive: We'd done this movie called "The Fan" with Tony Scott directing and it was down in Anaheim. I was still young and full of piss and vinegar, and I'd get up at two in the morning, be at the set on three because they were shooting all night. And Tony said, "What the f*** are you doing here, man?" I said, "Well, all those extras, haven't you shot them out by now? Can't you get rid of them?" He goes, "Oh yeah, okay. Skotch, get rid of them." Jim Skotchdopole was the first AD on it.

Cut to a couple of weeks later, I'm back in my office and I get this phone call and it's the head of legal. He's going, "Ray, Ray, we got to get down on the set right away." I went, "What's going on?" He goes, "I've got SAG calling." Apparently, they had the Jumbotron out and they cut for lunch and it was Skotchdopole's birthday and the second AD hired a stripper to come and dress as a cop. And we had brought in all these church groups with little ladies to staff the extras. Those were back in the days where you didn't do all the CG extras.

"Oh my God." So me and the head of legal go down there, and the first thing the head of legal goes is, "Who's got the tape of that?" Bury the evidence. That's the first thing that a good lawyer's going to do ... We made a policy that I basically had to go out to every single movie set and give the sexual harassment spiel. So that was my first journey down to Mexico. [...]

So anyway, we go down there and I give that kind of spiel and all that kind of stuff. And it happens on that day, they're doing a screen test. And Martin had three women in mind for the role that Catherine Zeta-Jones got. And he had just done a Bond movie and he wanted his Bond girl. [There was Catherine], and then there was a third one. So we're set up in this little scene, like a little stage, and there's a horse eating some straw, and the scene is the girl is brushing the horse and then turns around and delivers a line. That's it.

So the first woman does it, and okay, great, it's great, looks great. Next woman comes in, she does the same thing. Me and Martin are there with the DP just looking through the lens. Great. Catherine Zeta-Jones comes out and she starts brushing the horse.

And I don't know if you know much about horses, but there's the term when a male horse "drops." When a horse drops, a male horse's penis comes out of the sheath and it just keeps coming out, and it's fairly large. And [that happened] the minute she started brushing the horse, and Martin and I are just going, "That's the one! The horse knows!" [laughs] Now, sorry if that was a little off-color. I didn't mean to offend anybody, but it was kind of a classic story, so I couldn't help myself.

John Gertz, co-producer: I would like to talk about the nobility of character and the Anthony Hopkins character, his pathos and emotionality, and the way that Banderas and his character raised to that same level of nobility. That, to me, really stands out as a magnificent quality. Hopkins was magnificent to see or to work with — a very, very lovely human being. Very, very nice man.

George Parra, first assistant director: [Anthony Hopkins is] one of the great actors of all time. He, of course, has a British accent. It's there, will never go away, et cetera, et cetera. And we did a lot of camera testing for many different things, costumes and looks and all that kind of stuff. And I don't remember who — and even if I did, I wouldn't say who did — but somebody wanted to test Anthony without his British accent. So we put him on stage, and we did a camera test. He was in wardrobe and makeup. And he came in and did a scene without his accent. During the test, it was going on, and I remember standing next to Martin and Doug Claybourne, and they kept looking at each other saying like, "What's going on?" because you, as an audience, get so accustomed to Anthony Hopkins.

No matter if he's supposed to play a Spanish lord or whatever it was — Mexican, Spanish — and then, he comes out with a British accent, that's what you want. So when we saw [the footage without his natural accent] in dailies, we all started sort of laughing, because it was so absurd. And Anthony turns around and he goes, "So I guess I get to play it in my mother tongue," or something like that, and everyone laughed more. I mean, if you notice in the film, he's got a British accent, but nobody cares. It's much better. It's like, "Why would a guy like that have a British accent?" But after you get over it, because, "Oh, it's Anthony Hopkins." You don't care.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: Because we had people from all over, we had Mexicans, we had Cubans, we had Welsh, we had British — this is not a Mexican team — they had to figure out what they were all going to speak like. What is this "speaking in English, but with a Latin accent" thing going to be like? And they kind of uniformly had to decide where they were going to land in terms of what they all sounded like. And I don't know that they totally succeeded. At a certain point, they decided they were going to call it an Atlantic accent for all of them, which is some random, made-up thing. But some of them were more successful than others at covering their Welsh or British accents. It's not a full commitment to Spanish, it's like bad Brits trying to speak Spanish. So I thought that was really interesting at the very start, was just all the conversations around what their accents would be. And a lot of the dailies that got sent back to Spielberg and the team had a lot of comments about, "What is that?" So there was a lot of working out that whole mess.

Casey O'Neill, stunt double: I remember talking to Anthony Hopkins before ... it was a scene where he jumps off the balcony and lands onto the horse. So I was there for that. And I remember he would talk just like we are now, and then, "Hey, you ready, Mr. Hopkins?" "Yeah. Okay." He turned to the camera and they'd say, "Rolling, action," and he was completely — I don't know how he went from this kind of a conversation to so serious and so good. It was unbelievable to see that right in front of your eyes. You're like, "Okay. That's why he's who he is, because he's that good."

Phil Meheux, director of photography: Hopkins, I felt he thought it was a little beneath him a little at the beginning. In fact, him and Martin got into an argument. We were doing one scene. They've got an invite to this party, and they arrive. Hopkins is talking to him, and say, "Charm, you have to have charm," like that. He's saying all of that, and Hopkins would only do two takes and walked away. Martin said, "Well, hey. Wait a minute. I think I'm not quite happy with Banderas. I think we need to just have another go." "Well, I don't like to do more than two takes. I mean, this material is not worth it," like that.

So that was a sort of tense moment, but we got through the evening. We got through the job, and then we showed Tony the rushes that we'd had up to that point, which included some of the horse work and some of the sword fighting and all the rest of it. Bless his heart, he suddenly realized that this film wasn't quite what he thought, and it was actually better than he'd actually imagined. From then on, he was very much on our side.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: I had to organize tanning salons in Mexico City for everybody, because they were all so pasty. I think Tony Hopkins went three times. The first two times I was like, "Still don't look dark. Still don't look Mexican." So we had to keep sending him back to the tanning salon ... The actors hate when the coordinators tell them they have to go do stuff like that, so they reluctantly did. But it's always our job when the executives see the dailies and they go, "Somebody has a zit. You have to get them to a dermatologist, stat." And then you have to have that conversation with the talent like, "I really don't want to have to tell you this, but I've got an appointment with a dermatologist and you have to go now."

George Parra, first assistant director: The other [story] behind the scenes, it was really interesting, is we were a Directors Guild of America shoot. Martin's a DGA member, I am, Doug is, everybody, four or five of us. So we brought in our crew. My ADs were American. And the DGA had given us a guy named Jorge who was bilingual. He's no longer an AD. He went on to become an attorney, and he left the business. But Jorge and I kept in touch for a while. Educated kid, grew up, I think, in New York or something. Anyhow, he was the guy who, on a daily basis as a trainee, knocked on the trailers and got the actors into makeup and hair and did the production reports, and that was his job. But now, the Directors Guild rule is that they have so many days per film. They place you in a job as a trainee. It's a very difficult program to get into. I don't know if you're aware of it. I don't know what the numbers are now, but it used to be something like 2,000 people take the test, and 100 get into the final interview phase, and something like 20 make it yearly. It's a very small percentage, like getting into NYU or something.

So his days were coming up, and he had to be replaced and put onto another film, and everybody knew it, and it was like he's with family. So I was on the set, and somebody said to me, "Anthony would like to see you in his trailer." And I said, "Okay." And when Anthony Hopkins wants to see you, you go see him. So I replaced myself with my second AD, and I went to his trailer when I could. And he goes, "Come in, dear fellow, sit down. Sit down." So basically, the gist of that meeting was that he said, "Look, I know that Jorge has to leave, and I know how valuable he is to not only the production, but to me." They got to be very good friends. I mean, this is like a 24-year-old kid.

He said, "Tell the producers that I would like Jorge to stay, and I will pay the difference in the salary out of my pocket," which was tens of thousands of dollars. I can't be exact on the number. And I thought that was one of the most unselfish, wonderful ... so I went to the set, and I said, "So here's the deal." And immediately, Doug Claybourne, the producer, said, "Well, if he's offering, we're not going to say no." I mean, we can't say no to that request, because it doesn't cost production anything. So we called the studio, and that was it, done. And Anthony Hopkins paid for Jorge out of his own pocket. So he stayed for another two or three months on Anthony's dime.

Chapter 8: Production

Production began in Mexico on January 27, 1997.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: We took over the production stages and offices from the "Titanic" movie that had just pulled out. So people kept asking us if we knew where Leonardo DiCaprio was, and I'm like, "Not the same movie. Sorry." So we kind of slid into their location when they abandoned it to go to the next location. But it was the only big studio in Mexico City, and where all their telenovelas and all their movies happen.

And being a big L.A. team, we basically were blowing the power circuit for the whole neighborhood over and over again. And we had landlines, and the production office in L.A. would be asking us to get stuff done, or why aren't we answering the phone? And we'd be in this super hot, un-air-conditioned office with no power and we wouldn't hear the phone. They could hear it ring, and they were so mad we weren't picking it up, but it wasn't ringing on our side. We were just sitting there dying of heat exhaustion, trying to get stuff done. But there were a lot of times I went to set to get paperwork signed because we had daily paperwork that had to go back to the studio, and they were always mad at me if it didn't happen that same night. But we literally had one plug in the wall, the power kept going out, old school computers.

It was like they were so far back in terms of tech at that time that it was like, "Guys, if two of us get on the phone at the same time, the whole power for the neighborhood goes out. You just got to give me a minute. If it's ringing and we're not answering, it's not that we're not there, we just don't hear it ring."

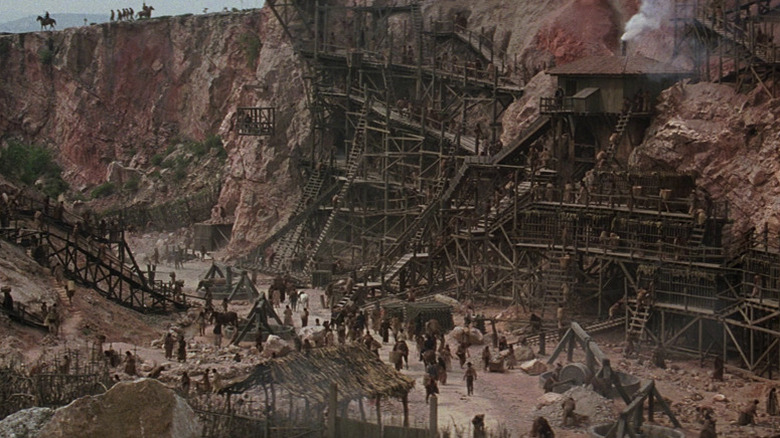

George Parra, first assistant director: The actual shooting was long. I think it was 110 days or something like that. Very, very long production schedule, a lot of traveling all through Mexico. We didn't just do Mexico City. We went all over the countryside to different places. I mean, shooting the party sequence was spectacular, with the costumes and the extras and the lighting and all that. All the big action sequences, the finale at the mine with the explosions, and the fires, and the sword fighting, and the villain dies, et cetera, was very time-consuming and grueling. Physically exhausting. Somehow, we made through it without many injuries at all — nothing dramatic, I remember.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: We had seven company moves, which my team was in charge of making happen, and a cast of thousands, basically, that we were moving each time. I just remember at the very start of production, the production team hosted a big dinner at The Palm in Mexico City. It was this massive room, and all of us were sitting around this big square table. And I have photos of that night, and everybody looks so optimistic, and so excited to be there, and so rested and young. And then I have, in my photo album, as you go through seven months of hard time in Mexico, we start looking super skinny, black eyes from lack of sleep, exhausted, like we've seen some things.

Doug Claybourne, producer: Do I remember anything about the locations? I mean, just that they were extraordinarily beautiful, far apart, and a challenge to set up and get people from place to place. I just remember that we started out on stage and we just kind of went from place to place. I can't remember the names of all the places. Tlaxcala, which I think is where the big first set was, where all the people into the town and where Zorro comes in, both the old and new Zorro together, which is a great sequence. I just remember it was a very exotic location to be on, and our production designer was wonderful. She did a great job, Cecilia, and of course Martin had just done one of the big James Bond movies and he was amazingly well-prepared.

Casey O'Neill, stunt double: The haciendas, a lot of them were already there, but then they added on to some stuff to make it work for the story. But just the scenery and being in Mexico and shooting that movie there was so necessary, I think, for the story and just for the feel of all of it to do that. Because now they just make movies ... if it's New York, it's in Toronto. It is not the same thing. So it was really nice and a unique opportunity to actually be in Mexico at those remote locations and shooting in those haciendas and at those amazing sets that they built.

George Parra, first assistant director: [Martin Campbell's] cinematographer at the time was Philip Meheux. And they're both like Abbott and Costello sort of humor, like they're British. I think Martin's from New Zealand, but he lived in London for a long time, and Philip is British. So they have that sort of dry sense of humor all day long [...] I mean, [Martin] and I and Phil, we worked our butts off. It was a labor of love. It was hardcore. Good thing I was 25 years younger. It was intense. We were working six-day weeks and a lot of driving, a lot of driving. Martin had a Suburban and a driver. And it was usually Phil and I in the back with another producer, David Foster, was in there. And there were four of us, and we drove and drove. We drove forever, tens of thousands of miles.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: The places we were staying at were very rustic. When SAG-AFTRA requires anybody above the line to be in a first class accommodation, you're like, "This is all they have." We booked completely the two hotels in Tlaxcala, one was considered above the line in town, and as far as I know, it was the only hotel in town. And then we were in a country hotel up in the mountains, which was really rough. It was very low tech, very rough ... I have lifelong friends from this movie that I still see all the time and still talk to all the time because we had seven months isolated from the rest of the world. I call it one of my seven-month blackout periods, where any number of things could have happened in the outside world, but we wouldn't have known because we had so little contact with anybody outside the movie for seven months.

George Parra, first assistant director: [Early on in production], everyone started catching a flu. And when the flu goes through a crew, it's hard to avoid it, because you're in direct contact. This is way before masks. Nobody wore masks. And everyone's exhausted and working long hours, and so on and so forth, and coughing. People are coughing, and just like this cold, flu-ish thing going through. And I didn't catch it, but Martin did. A lot of people did.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: He wasn't a big guy to begin with, but we started calling him Skeletor because he'd lost so much weight. And it was unclear if he was going to be well enough to continue as the director, really from the very get-go.

Doug Claybourne, producer: You get off the grid and you start eating vegetables and eating salads and that kind of stuff, and drinking water or using ice cubes that were put together with local drinking water, you can pick up that bacteria, and very quickly, you've got the runs. And it's not easy to get rid of. So I think that's what happened with a lot of people, was they just ended up not drinking bottled water and catching this local bacteria.

Alyssa Wittenberg, production coordinator: We were plagued with stomach stuff the entire seven months because there's no food safety. If they didn't just overcook it to death or you saw it get killed and cooked for you, there's no refrigeration, so we would have entire teams go down with stomach bugs. I was passing out Mylanta, Pepto, and anything else I could throw at them. "We just need somebody in your department to show up on set today. The show must go on. Can one of you remove yourself from the floor of the bathroom and join us on set?"

George Parra, first assistant director: And we had met doctors, giving us these antibiotics and cough syrup and what have you.

Mark Ivie, assistant sword master: The doctor who was down on the other end came down over to me, and gave me this — I don't know what it was. It was this chalky thing. And suddenly I was okay again. It was that fast. I was throwing up in the trash can, and he saw it, and he came up, and he gave me this little powdery thing. And I was back on my feet ready to go. And they knew what to use, but I certainly didn't.

George Parra, first assistant director: So everybody got really sick. And there was a point we were shooting at night where Martin was really sick. He was coughing up a lung. Horrible. He could barely talk, and he'd look run down. His eyes were all watery, but he kept going. He's like the Duracell Bunny. This was a big film. He didn't want to let anybody down. And I'm in close contact with him. And I remember his wife, when she was visiting during prep, saying to me, right as she left, she said, "George?" I said, "Yes?" I can't remember her name. "Do me a favor." And I said, "Yes?" And she said, "Look out for Martin, because he'll keep going till he drops." I was like, That's weird.

So at that moment, that night on the set, I said to myself, "Oh, that's what she meant." It occurred to me over the next half-day, and he kept getting worse and worse and worse. And I said to Doug Claybourne, I said, "Doug, we need to meet in Martin's trailer at lunch." He goes, "What about?" I go, "I'll tell you when we get there, it's just something important." So we got there, Martin was in there coughing and coughing and coughing. And they usually brought him his lunch. And he was coughing and coughing ... Doug came in and we sat down. And I brought Phil Méheux, his old friend of many films, and we all sat there, and I said, "Guys, I'm here to tell you that I'm the safety monitor on the film as the first AD." I said, "We can't continue with Martin." And Martin got upset. He was like, "No, I'm fine." And I go, "Marty, you're going to get worse and worse." So Doug looked at me, I looked at him, and he didn't hesitate. He just went, "Done." He goes, "You're right. We can't continue." And we were off for two to three [days], maybe three [days]. We went back to Mexico City, and he ended up in the hospital. He had pneumonia, and that's dangerous. So yeah, it was a big thing.