Sharon Stone Is The Best Actor Ever

When Sharon Stone steps in front of the camera, it's basically over for her costars. Even in an underwritten role (and she spent the first decade of her career making the most out of nothing parts), she's the person you've got to watch — and it's not always to the film's benefit. After she finally earned her richly deserved stardom, she had a propensity to dominate. This could be a product of having been passed over for major roles until she was in her thirties. Whatever the reason, once she seized the spotlight, she wasn't letting go, and she stole whole movies from very good actors as a result.

Unfortunately, many of these movies weren't worth stealing, and this, coupled with a Sean Penn-esque surfeit of candor in interviews (e.g. the time she suggested the devastating Sichuan earthquake in 2008, which killed over 69,000 people, was possibly karmic retribution for the Chinese government's brutal oppression of Tibet), has possibly hardened moviegoers, who should be lobbying for a career revival as they've rightfully done for greats such as Michelle Pfeiffer, Meg Ryan, and Debra Winger, against her. But this is not entirely Stone's fault. She would've been poor casting in the kinds of secondary parts that introduced us to the aforementioned.

Because Sharon Stone was never an ingénue. She was formidable from jump. She was "Shaz." And as Richard E. Grant recounts in the hilarious "Hudson Hawk" segment of his memoir "With Nails," she knew how to play the Hollywood game to a seemingly pathological degree. But she was a (soon-to-be) star out of time. She was a Golden Age glamor queen relegated to playing the concerned wife in dopey 1980s action flicks — until a Dutch satirist with blockbuster bona-fides cast her in the role of a lifetime.

The breakout

"Basic Instinct" is Alfred Hitchock's "Vertigo" with herpes. Written with hedonistic fervor by million-dollar spec king Joe Eszterhas, it's a vicious, high-style skewering of Reagan-era male overcompensation. This is not impotence. Michael Douglas' Detective Nick Curran can f***, but he's sport-f***ing. He's screwing his department-appointed therapist (Jeanne Tripplehorn) out of seeming defiance. He'll lay off the booze and coke for the good of his career, but he's going to get some below-the-belt satisfaction in return. Because sooner or later, a hard-charging cop like Nick always gets his way.

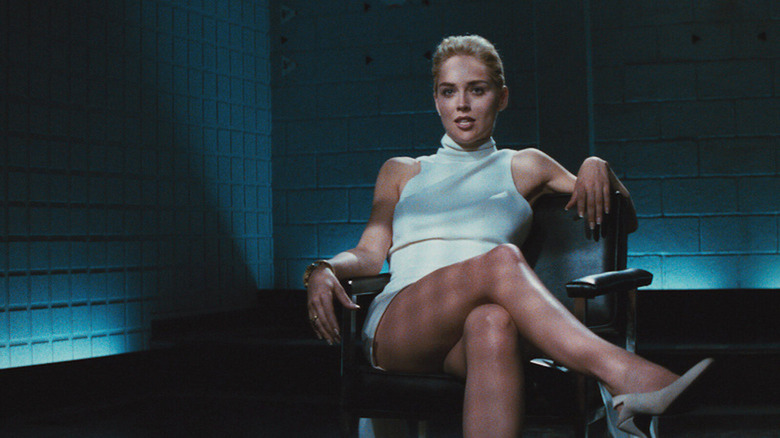

Sharon Stone's Catherine Tramell knows guys like Nick. She knows how to get them off, and, in turn, how to get herself off the hook. Stone's introduction in "Basic Instinct" is an all-timer. After Nick and his partner announce their presence on the back deck of her seafront compound, she rolls her eyes, takes a contemptuous drag off her cigarette, and flicks the butt into the roiling surf below. She's already won.

Douglas was a few years removed from a Best Actor win for playing the reptilian Gordon Gekko in "Wall Street," but Stone devours him in every scene, and you get the feeling he's okay with this. Catherine is a crime novelist who brazenly turned her premeditated murder of some sleazeball music industry millionaire into the plot of her most recent book. She's guilty as hell, but at no point during the film do we think she'll get her comeuppance — primarily because we don't think she deserves one. Verhoeven's film isn't really about solving the crime; it's about delighting in Catherine slithering out of trouble for offing a rich dirtbag.

Stone is in steely control throughout, most notably in the film's legendary interrogation scene, where she toys with a roomful of overmatched cops who might as well stop asking questions and start throwing dollar bills. They're all drooling marks. And so are we.

From Mars to San Francisco

Stone made a strong impression in her previous films, but it wasn't until Verhoeven placed her opposite Arnold Schwarzenegger's memory-wiped Quaid in "Total Recall" that she popped as a deliciously nasty femme fatale. The era's action-movie conventions dictated that she must meet a cheer-worthy death (replete with a classic Arnold quip), but everyone left that movie wondering who the hell she was, disappointed that she'd died so soon, and desperate to know when they could see her again.

Yes, Stone was fashion-model gorgeous, but what hooked us was her knowing carnality. In the early 1990s, erotic thrillers were all the rage in theaters and, especially, video stores. They were stylish, steamy affairs that offered soft-core titillation outside of the stigmatized, cordoned-off porn section. Many fine performers shed their clothes and hurled themselves into wildly horned-up villainesses, but Stone was the only actor to play her character as a self-aware archetype. She lives in her fiction, and she loves it. She's dealing with hard-up simps, and she gets off on killing them. It's lurid, cold-hearted stuff, but this was the state of the male in 1992, and these panting jackasses deserve their fate.

If you're not rooting for Catherine, you're watching "Basic Instinct" the wrong way. There wasn't another actor alive at the time who could've pulled this trick off, which proved a problem for Stone. There wasn't another Catherine Tramell on the landscape.

The career

Hollywood simply wasn't ready for Stone. It took a devious genius of Verhoeven's magnitude to harness her talent and attitude. Before that, she was game as a Kate Capshaw substitute in Cannon's junky "King Solomon's Mines" duology (great Jerry Goldsmith scores), and professionally present opposite Steven Seagal and Craig T. Nelson in, respectively, "Above the Law" and "Action Jackson." Her most amusing pre-"Basic Instinct" turn can be found in John Frankenheimer's middling "Year of the Gun," where she seems consistently miffed to be playing sexy second-fiddle to cardboard, Brat-Pack castoff Andrew McCarthy.

Post "Basic Instinct," Hollywood envisioned Stone as the Queen of the Erotic Thriller. These dreams were dashed with Phillip Noyce's "Sliver," a Stone/Eszterhas reunion that squanders a provocative premise from "Rosemary's Baby" author Ira Levin. She looked bored opposite Richard Gere in Mark Rydell's aimless "Intersection," and utterly disgusted by Sylvester Stallone in Luis Llosa's deeply stupid "The Specialist" (the stars' big sex scene is twenty million dollars' worth of passionless, A-list body-mashing — in other words, a queasy must-see).

The great tragedy of Stone's career is that Sam Raimi's "The Quick and the Dead" was not a hit. A giddy Spaghetti Western pastiche, this was Stone's opportunity to redefine another archetype. She could've worked a cheeky, gender-swapped variation on Clint Eastwood's laconic Man with No Name, but she brings a bruising vulnerability to her gunfighting protagonist. It's a spectacularly entertaining film (and Stone deserves credit for insisting on a then up-and-coming Russell Crowe as her ostensible romantic interest), but Sony couldn't figure out how to market a female-fronted Western, and the movie underperformed.

A despicable Stone-walling

After the failure of "The Quick and the Dead," she appeared in Jeremiah Chechik's remake of Henri-Georges Clouzot's classic thriller "Diabolique" and was let down by the limp material. She went Oscar shopping as a death row inmate in Bruce Beresford's "Last Dance," and lent her star power to Barry Levinson's adaptation of Michael Crichton's "Solaris" rip-off "Sphere." Both stiffed with audiences and critics alike. She was wonderful as the loving mother of a hyper-imaginative, terminally ill child in Peter Chelsolm's "The Mighty," but even the campaigning power of Miramax couldn't get her more than a Golden Globes nomination.

Stone survived a near-fatal brain hemorrhage in 2001, and scored a lovely, low-key comeback in Jim Jarmusch's "Broken Flowers." After years of false starts and lawsuits, Stone finally reinhabited Catherine Tramell in "Basic Instinct 2." The film lacked Eszterhas' lurid madness and Verhoeven's diseased, diamond-cutting directorial skill, but Stone roared back to overpowering form, bearing her soul and body with garish abandon. Technically and narratively, it's a bad movie, but Stone, having survived industry and physical death, is spellbinding as she exorcises a whole raft of personal demons.

That same year, Stone gave her finest performance in a decade as an Ambassador Hotel beautician in Emilio Estevez's earnest, under-appreciated "Bobby." Her scenes with Lindsey Lohan's young, uncertain bride are especially touching when you consider how the industry failed both actors. There's a heartbreaking warmth to their interactions; they're two women who, a generation apart, are prisoners of sexism.

Stone seemed on the cusp of a comeback fairly recently via her turns in Steven Soderbergh's "The Laundromat" and "Mosaic," but the director's cerebral genre exercises failed to move the cultural needle. If I were a working filmmaker, I'd be champing at the bit to be the person who thrust Stone back into the spotlight she craved and owned decades ago. And I'd look to her Oscar-nominated 1995 triumph for inspiration.

The defining performance

I'm cheating a bit here because Catherine Tramell is not only Stone's defining role, she's one of the most culturally vital characters in film history. But Tramell was the hard-hearted proof-of-concept that brought Stone to Martin Scorsese's "Casino."

The world could be Ginger McKenna's oyster. She's a former sex worker who's vaulted into the world of Las Vegas stage shows, but she's got a penchant for chip hustling. Tangiers Casino manager Ace Rothstein (Robert De Niro) doesn't care; he's enthralled with the knockout's shameless ways, and, even though she is the exact element he's trying to keep out of his big-money establishment, he falls in love with her. They marry. And if Ginger had her wits entirely about her, she'd know that's when she won. Ginger, however, is stuck in an abusive relationship with a seedy con man named Lester Diamond (James Woods). He granted her entree to the fringes of the high-rolling world she's penetrated via her own natural guile. Ginger should jettison Lester, but he knows her every weakness. He trained her. He knows how to bring her to heel, and how to get her to betray her own husband for a quick-and-easy score.

Ginger is a tragically misshapen figure. She's every bit as savvy as Catherine Tramell, but she's been consigned to a jackpot hell. She can't play the long game. She has to win it all with every role of the dice. This is what Vegas does to people. She's married a powerful man and started a family, but there's always a better, bigger score right around the corner. She's an operator, but, like most Vegas burnouts, she's still a dreamer. Watching Stone break apart during the second half of Scorsese's game-land epic hollows out your soul. Falling prey to a two-bit scumbag like Woods' Lester feels like a violation. Stone's supposed to win — and she did, albeit briefly.

I look over Stone's filmography, and I see a woman punished for playing the '80s-'90s blockbuster game too well. I watch "Casino," and I get angry that we so rarely saw her at her best. The house wins, but Stone's still shooting dice. Who's going to stake her?