In Albert Einstein, Oppenheimer Found An Unlikely Ally With A Very Different POV

Spoilers for "Oppenheimer" follow.

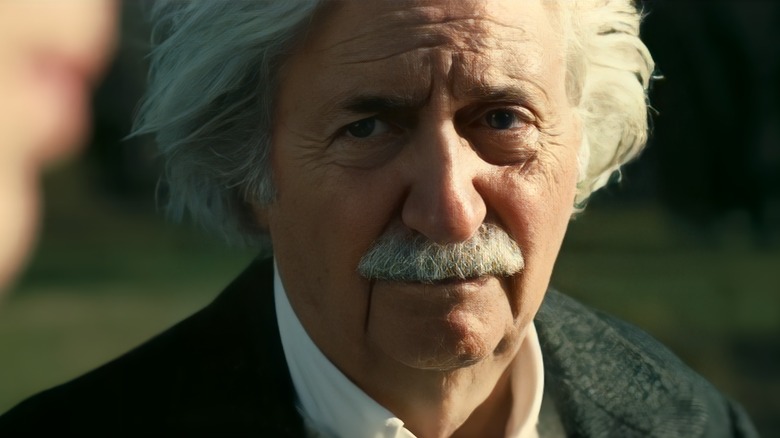

Much more so than J. Robert Oppenheimer, Albert Einstein has a reputation increasingly disconnected from who he was as a person. Known now primarily for his crazy hair and his German accent, Einstein's most commonly talked about in modern pop culture as that guy who gets a bunch of famous quotes falsely attributed to him. No, Einstein was not hanging out at parties in the fifties giving zingers in response to Marilyn Monroe's flirtations, nor did he fail math as a child as is commonly claimed.

What doesn't get talked about as much is his complicated relationship with the U.S. government. He moved to America shortly before Hitler rose to power and almost immediately drew suspicion from the FBI for his left-wing political views. "Agents listened to the physicist's phone calls, opened his mail and rooted through his trash in the hope of unmasking him as a subversive or a Soviet spy," historians have noted. "They even investigated tips that he was building a death ray. The project came up empty handed, but by the time Einstein died in 1955, his FBI file totaled a whopping 1,800 pages."

None of this was touched on in "Oppenheimer," but it all sure sounds familiar now. Oppenheimer was also a guy with lots of left-wing sympathies, and, as we saw throughout the film, he too was subject to relentless surveillance from the FBI, the results of which were used to destroy his career. As much as the American government needed scientists throughout the war, the fact that these brilliant scientists tended to skew leftward was a destructive source of unending conflict. For both Oppenheimer and Einstein, this conflict nearly ruined them.

Where Oppy and Einstein differed

Most of the conflict between Einstein and Oppenheimer came down to the fact that they were physicists of two different generations. Most of the innovations in the new field of quantum mechanics were made by younger scientists, and Einstein often didn't find their ideas convincing. Younger physicists like Oppenheimer considered Einstein's "stubborn refusal to embrace the new physics" to be a "sign that his time had passed," as historians Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin noted in their biography, "American Prometheus," which Nolan's film is based on. When Oppenheimer met him for the first time in the late 1920s, he reportedly told his brother that Einstein was "completely cuckoo."

Another big early difference is that Oppenheimer was the director of Los Alamos with a clear-cut role in creating the atomic bomb, whereas Einstein's hands were largely clean. Beyond signing a letter to Roosevelt in 1939 urging him to start a nuclear program to beat the Nazis, Einstein had no involvement in the project because, as a German with left-wing views, he was denied security clearance. (He also just didn't seem interested.) As a result, scientists at Los Alamos weren't supposed to interact with him at all; the scene in the movie where Oppenheimer asks Einstein for help figuring out if their experiment would destroy the world was entirely fictional.

Their conversation at the end of the movie, the one that accidentally led to Lewis Strauss hating Oppenheimer for the rest of his life, was also apparently fictional. Yet despite the fact that Nolan took the biggest creative liberties with Einstein's scenes, the friendship between the two scientists was certainly real.

A healthy amount of regret

Beyond their left-wing views, maybe the biggest thing the two scientists had in common was their regret towards their role in the atomic bomb. Oppenheimer's guilt is obvious, but even Einstein felt bad about the limited role he played in it. "Had I known that the Germans would not succeed in producing an atomic bomb, I would never have lifted a finger," he told Newsweek in 1947. No matter what your intentions were, it's got to be devastating to realize that your life's work has led — directly or indirectly — to the possible destruction of all of humanity.

But whereas Oppenheimer dealt with his guilt by involving himself in U.S. policy, trying to use his fame to influence the Truman and Eisenhower administrations as much as possible, Einstein responded by removing himself from politics altogether. As the anti-communist hysteria landed on Oppenheimer's door, Einstein suggested he simply give up on America and move somewhere else. (After all, Einstein himself gave up on his home country back in the 1930s.) According to "American Prometheus," Einstein argued that Oppenheimer "had no obligation to subject himself to the witch-hunt, that he had served his country well, and that if this was the reward she [America] offered he should turn his back on her." Of course, Oppenheimer refused the suggestion. He was an American patriot despite all its flaws, and he wasn't going to abandon his country any time soon.

Time comes for us all

The bitter irony is that what Oppenheimer goes through, while far more dramatic in nature, is basically the same as what Einstein went through. He was once considered the most brilliant physicist in the world, but was soon surpassed by younger physicists and cast aside by the government that no longer needs him. "You all thought that I'd lost the ability to understand what I'd started," Einstein tells Oppenheimer in their private conversation near the beginning and end of the film. "Now it's your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievement."

A lot's already been made of the movie's decision to split its story into three main timelines, but the main benefit is the way it emphasizes how quickly time goes by. Years pass between Oppenheimer's downfall at the boardroom inquiry and Lewis Strauss's downfall at the senate hearing, but the film jumps back and forth between these events in the blink of an eye. It takes several years for karma to reach Strauss finally, but from our perspective, it hits him almost immediately.

"The whole film is about consequences," director Christopher Nolan told Vulture in a recent interview. "The delayed onset of consequences that people often forget." This is the central idea behind Oppenheimer and Einstein's big conversation, the one that inadvertently sets off its own chain of events on its own. Maybe setting off that first bomb didn't contain an immediate chain reaction that destroyed the world, but maybe the chain of events leading to Armageddon have in fact been set in motion. As the movie cuts to modern-day missiles, it's clear that the "when" of it all doesn't really matter. When the end of the world comes, it'll inevitably feel way too soon.