Dustin Hoffman Is The Best Actor Ever

The story isn't entirely apocryphal. Laurence Olivier, the twentieth-century god of Shakespearian acting, really did, in a moment of amused exasperation, respond to his "Marathon Man" co-star's intentionally induced mental and physical exhaustion by asking "Dear boy, why don't you try acting?" It just wasn't the old-school smackdown of method acting that traditionalists have been gloating over for years, but, rather, a fatherly shrug when faced with the immersive, emotionally supercharged approach to performance championed by Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner.

Olivier came from a drastically different school of acting, but he understood what Dustin Hoffman represented. Though Marlon Brando was still the rock star of method acting in the mid-1970s (though he was starting to slip off the rails with undisciplined turns in oddities like "The Missouri Breaks"), Hoffman had become its New Hollywood soul. He lacked the sex appeal of contemporaries like Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, and Al Pacino, and couldn't project the threat of violence exuded by his ex-roommates Gene Hackman and Robert Duvall. The key to Hoffman was his insecurity. At his 1970s and '80s peak, Hoffman burrowed deep into his own frustrations and connected with disaffected Baby Boomers who desperately didn't want to be their parents.

Babe, the Ph.D. candidate protagonist of "Marathon Man," is riddled with these insecurities. He's also got a torture-happy Nazi war criminal on his ass, which ultimately lands him in a dentist's chair for an excruciatingly protracted bit of novocaine-free drilling. So, to capture Babe's hysteria, Hoffman, who was going through a divorce at the time, ran himself ragged (which included making the debauched scene at the notorious Manhattan nightclub Studio 54), and, somehow, held his own with Olivier in a scene for the ages (though not for the squeamish).

There is no "try" to Hoffman's acting. The effort is right there on the surface, and it matches his characters' searching nature. Where do they fit in this world? Do they fit in this world? It's the question Hoffman, through his messed-up characters, keeps asking.

The breakout

Benjamin Braddock is a young man of whom great things are expected. He's just earned an unspecified bachelor's degree from an unnamed East Coast school, and has returned to his parents' house in Pasadena to be paraded about as a success story in the making. His rich parents are loaded with rich, well-connected friends; all he's got to do is call his shot, and he'll be pulling down a fabulous salary before he turns 30. He'll get married, sire a couple of kids and retire early: the American dream personified.

But from the opening shot of Benjamin gliding through LAX on a people mover, scored to Simon & Garfunkel's "The Sound of Silence," we're introduced to a new kind of coming home, the meek opposite of World War II soldiers being greeted by marching bands and adoring crowds. Hoffman's vacant, straight-ahead gaze is that of a kid condemned to upper-middle-class mediocrity. His ennui only grows more palpable as he spends his summer swilling suds in his parents' swimming pool while engaging in an affair with the bored/amorous Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft).

Hoffman was almost 30 when Mike Nichols cast him in "The Graduate," but despair is an ager, and, given the (barely mentioned) social upheaval of the time, his Benjamin looks properly defeated. Our sympathies are challenged, however, when Benjamin falls clumsily in love with the Robinsons' daughter Elaine (Katharine Ross), who, upon learning of his affair with her mother, flees to Berkely. This Benjamin is a clingy creep; he's relentlessly stalking a girl with whom he has nothing in common save for a pre-programmed future. But thanks to the expert tutelage of Elaine's mother, Benjamin is now well-practiced in the art of manipulation. He knows how to convince a less worldly person into believing the last thing they want in this world just might be, if only for a moment, their heart's desire.

The breakout part 2

That moment arrives during the film's frantic final ten minutes, when Benjamin disrupts Elaine's hastily arranged marriage. The couple flee the bedlam to the back of a city bus, where we watch their elation dissipate as the life-altering implications of what they've done set in. Where do they go from here?

It's fashionable to ding "The Graduate" nowadays as a misogynistic celebration of male self-pity, but Hoffman hooks us early with his fidgety portrayal of a 20-year-old inclined to do what his elders ask of him – even if it's to sleep with the wife of his father's business partner. His pre-coital fumbling with Bancroft in the hotel room makes for one of the most awkward sex scenes in film history. Whether he's planting a long, passionless kiss on her lips right after she's taken a drag on her cigarette, or cringily cupping her breast (prompting a distracted Bancroft to fuss with a stain on her shirt, at which point he walks away and bangs his head on the hotel room wall), Hoffman wincingly conveys the terror of a kid who, sexually, is in way over his head.

Everyone's been there in some form or fashion (perhaps not with an older lover), so we can empathize with Benjamin without ever warming to him as a person — which is as far as Nichols wants us to take it. The specifics of Benjamin's dread are never voiced. He's just a mixed-up child of Southern California privilege who wants off this carousel of conformity, but marrying Elaine is no exit. Thematically, this could've been a tidy satire, a funnier "Catcher in the Rye," but Hoffman freights Benjamin with the crushing weight of a type of angst he can't yet articulate. He's old enough to know his character's destination, which lends his performance a knowing quality.

Benjamin doesn't know he's already lost, but Hoffman does.

The career

Born August 8, 1937, in Los Angeles, California, Dustin Hoffman had a slight connection to filmmaking via his father Harry, who worked for a time as a prop supervisor at Columbia Pictures. But there was no fast track to stardom. In his youth, his best shot at a career in the arts appeared to be as a concert pianist, but the acting bug bit him as an undergrad at Santa Monica College, which brought him to the Actors Studio in New York City.

There was, however, a meteoric rise to stardom after the commercial and critical success of "The Graduate." Having received his first Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, Hoffman was keen to demonstrate a versatility many critics did not believe he possessed. He demolished this misperception as loquacious street hustler Ratso Rizzo in John Schelsinger's "Midnight Cowboy," which earned him another Best Actor nod.

Now he had a reputation as a chameleon, which brought him to the performance showcase of Arthur Penn's "Little Big Man," where he disappeared under makeup as a 121-year-old man who recounts his larger-than-life exploits in the American West. Hoffman again challenged audiences' sympathies as a timid mathematician forced to defend his home and wife from a pack of vicious thugs in Sam Peckinpah's shockingly violent "Straw Dogs." He was well paired with Steve McQueen in Franklin J. Schaffner's distended prison saga "Papillon," and divisive as the self-destructive comedic trailblazer, Lenny Bruce, in Bob Fosse's "Lenny."

Hoffman is terrific in these films, but there was a grandstanding quality creeping into his work that smacked of Brando's descent into bizarre stunt performances, so it was a relief to watch him dial it back and play recognizable human beings in Alan J. Pakula's "All the President's Men" and Ulu Grosbard's "Straight Time" (an underseen, fantastically absorbing crime drama which was to be Hoffman's feature directorial debut). Hoffman won his first Best Actor Oscar in 1979 for "Kramer vs. Kramer" as a suddenly single father overwhelmed with the demands of raising his young son.

The career part 2

Hoffman took a break from movies after the triumph of Sidney Pollack's "Tootsie" to work through his obsession with Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman." The 1984 Broadway production was turned into a TV film for CBS, and while the supporting cast is sensational, Hoffman lacks the overbearing stature you expect from the character of Willy Loman. It's a daringly different take on the material, but Hoffman's antic physicality is all wrong. Loman is a giant, and Hoffman's histrionics are more buzzy than fearsome.

Elaine May's 1987 flop "Ishtar" remains a lamentable example of critical malpractice. Hoffman and Warren Beatty are cast against type as, respectively, a ladykiller and a klutz, but it never feels like a stunt. May gets a complete and total buy-in from her megastars as a pair of woefully incompetent songwriters, who disastrously warble through a stream of godawful ditties before getting caught up in an arms-dealing imbroglio in North Africa. The film has since been rediscovered, and Hoffman continues to sing its praises.

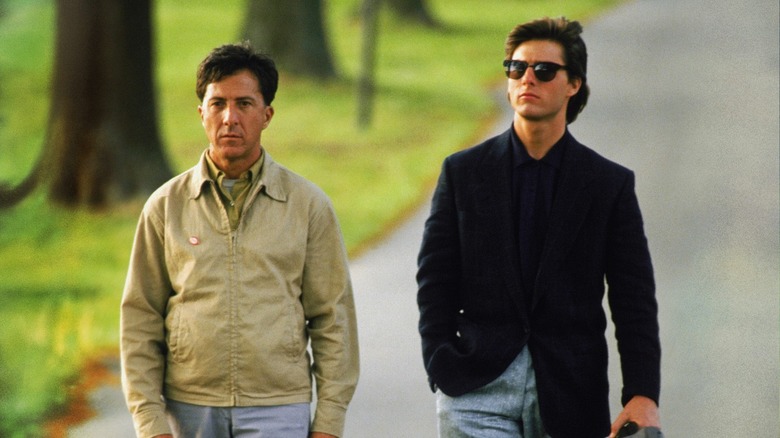

Hoffman won Oscar number two for the most astonishing disappearing act of his career as the autistic Raymond Babbitt in Barry Levinson's "Rain Man." There is, inescapably, a stunt quality to this performance, but Hoffman's commitment to the dignity of the character rescues it from caricature. He also gets a magnificent assist from co-star Tom Cruise, whose high-wattage charm is rendered ineffective here. His character can't coerce Raymond into doing anything, and it drives him crazy. Hoffman is technically stunning, but Cruise is the heart of the movie.

Hoffman's 1990s got off to a rocky start with a trio of misfires in "Billy Bathgate" (where he was badly miscast as gangster Dutch Schultz), "Hook" (having a campy hoot at Spielberg's expense), and "Hero" (a pricey, strangely overstuffed satire with about forty minutes of great stuff in it, most of it Hoffman's). From here, he eased off the gas, though I'll go to the mat for his uproarious Robert Evans riff in "Wag the Dog," his perfume shop owner in Tom Tykwer's "Perfume: The Story of a Murderer" and his ailing patriarch in "The Meyerowitz Stories." I'm not waving off Hoffman's last 30 years; it's just that his career was frontloaded with fireworks. And barring a late-breaking shocker, he'll never best Michael Dorsey.

The defining role

"Tootsie" went through multiple permutations before it landed on director Sidney Pollack's desk. Screenwriters came and went, as did the great Hal Ashby, who faced legal action stemming from unfinished editorial duties on his previous film. Stars such as Peter Sellers and Michael Caine circled the project early in its development. Everyone could smell a hit. But only Pollack and Dustin Hoffman viewed it as more than a cross-dressing lark.

This one hits close to home for Hoffman. Michael Dorsey is a struggling New York City actor whose difficult "method" reputation has all but blacklisted him from steady work. He teaches acting on the side, and seems to love his students, but he's terrified that he's aged past his big break. Alas, there's no Benjamin Braddock out there for him. Realizing his temperament has rendered him unhirable, Dorsey doubles down on method and becomes struggling actress Dorothy Michaels.

All great actors possess deep reserves of empathy, and it's clear at the outset that Dorsey has bitterly busted his antennae. But as Dorothy, he's suddenly dealing with new, albeit toxic stimuli, and he is instantly reborn as a performer. Emotionally, he's playing with house money; he can challenge sexist directors because his livelihood as a man, stunted as it is, is not at stake. So he hurls himself into the part and, Dorothy, by standing up for herself, gets a role on a network soap opera. Now the real immersion begins.

People love Dorothy for her forthrightness and kindness because Dorsey is playing her as a hero. His coworkers are his audience, and they're rooting for Dorothy to keep sticking it to Dabney Coleman's sexist director (who's carrying on an improper, mentally abusive relationship with Jessica Lange's ingenue, Julie Nichols). At a certain point, being Dorothy becomes a crusade for Dorsey, which is wonderful until Lange's widowed father, Les (Charles Durning), falls in love with her. Dorsey's deception isn't so cute anymore, and when he finally breaks character, we're heartbroken for Les.

Moreover, while Dorsey has learned a painful lesson in the indignity of being a woman in show business, we're left wondering if one man's enlightenment was worth all this emotional wreckage.

The defining role part 2

"Tootsie" arrived two years after Colin Higgins' "9 to 5," wherein three very capable women shatter the glass ceiling by turning the tables on their lecherous boss (Dabney Coleman, who excelled in these roles). Pollack's film might've felt like a retread had it been more about the industry's comeuppance than Dorsey's.

Dorsey isn't quite Benjamin Braddock, but Hoffman plays him as a selfish man who believes he's living a righteous life by encouraging his students and fighting the power as Dorothy. He's a shameless flirt who leads on his vulnerable, terribly lonely friend Sandy (Teri Garr), and, by being Dorothy, takes away a part that belonged to a woman. When Hoffman is Dorothy, he's playing the arrogance and, ultimately, guilt of Dorsey. This is a big studio comedy, so he has to go for big laughs on occasion, but his finest moment in the film is when he listens to Julie, a single mother who's one bad break away from becoming a raging alcoholic, open up about the misery of being a woman in the entertainment industry. We're watching Hoffman process this on two levels, and while we're glad Julie has someone to talk to for once, the betrayal — that she believes she's found a confidant, and will soon learn she got gamed by another man – is crushing.

"Tootsie" ends on a bittersweet note. It has to. But as sensitively dramatized by Hoffman, Dorsey's lie throws light on an awful truth, one that's still too true today. This is the highest form of acting you're likely to see. The method works.