Return Of The Jedi Gave The Original Star Wars Trilogy The Ending It Needed

Though "The Empire Strikes Back" is often regarded now as the best "Star Wars" film, the surprising runner-up in our poll two years ago was "Return of the Jedi," which is celebrating its 40th anniversary today. That "Jedi" should make such a strong showing was surprising if only because the film tends to take a slight critical drubbing in comparison to "Empire" and the first "Star Wars" movie, now known as "A New Hope."

With "A New Hope" and "The Empire Strikes Back," directors George Lucas and Irvin Kershner each carved out a distinct tone and vision for what the original "Star Wars" trilogy could be. Still, the contemporary love for "Empire" doesn't necessarily align with the immediate reaction audiences had to it back in the day. Last year, the Vice TV docuseries "Icons Unearthed: Star Wars" (which features a rare on-camera interview with "Return of the Jedi" co-editor Marcia Lucas, George Lucas's ex-wife) spliced in footage of one '80s fan exiting the theater, saying, "It could've been a better ending," in reference to the ending of "The Empire Strikes Back."

In a 1980 Rolling Stone cover story (via StarWars.com), Harrison Ford himself also said, "I have heard frequently that there is a certain kind of disappointment with the ending of the second film. I've heard people say, 'There's no end to this film.'"

Though its script coalesced late in pre-production, "Return of the Jedi" offers a definitive ending, and it's arguably the one "Star Wars" needed. From the standpoint of cohesiveness, the trilogy could have wrapped up in one of two ways: either by looping back on the vibe of "The Empire Strikes Back" or "A New Hope." It went with the latter, solidifying "Star Wars" as a fairytale with a happy ending, and we're better off for it.

'If it's not okay, it's not the end'

"Star Wars" always had the flavor of modern myth, and it would be reductive to say it was just for kids, though in "Icons Unearthed," second unit director Roger Christian does say, "George [Lucas] wanted to take 'Jedi' back to the nine-year-old audience. More like 'Star Wars.'"

With "Return of the Jedi," Lucas made a conscious move to appeal to the inner child, fertilizing the imagination of a generation of young moviegoers. John Lennon had been assassinated the year of "The Empire Strikes Back," but "Return of the Jedi" is the film that tells us Lennon was right and, "Everything will be okay in the end. If it's not okay [as in 'Empire'], it's not the end."

It's not the kind of movie David Lynch would have made, but his involvement with "Star Wars" will only ever be a fascinating "what if," since he backed out of "Return of the Jedi" and freed up the director's chair (really, the passenger's seat in Lucas's real-life Ferrari) for Richard Marquand. The Lynchian alternative to the "teddy bear luau," as "Empire" and "A New Hope" producer Gary Kurtz once characterized "Return of the Jedi," would have been a pyrrhic victory that might have left some of its target audience scarred for life.

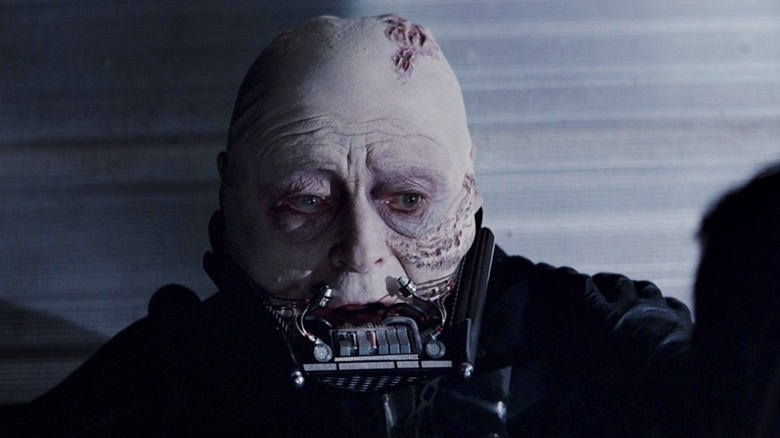

This is something Lucas deliberately sought to avoid when, as the DVD commentary reveals, he consulted a child psychologist for "Return of the Jedi" about how to deal with the continuing fallout of the revelation that Darth Vader was Luke Skywalker's father. It's not as if "Jedi" is bereft of adult emotion, either. Quite the opposite, as it seeks to redeem Darth Vader and shows how Luke has toughened up from a whiny farm boy into the galaxy's ultimate Zen warrior.

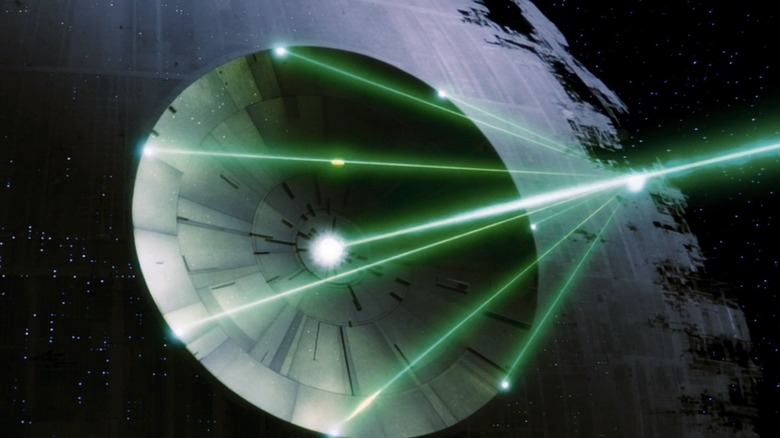

Return of the Death Star

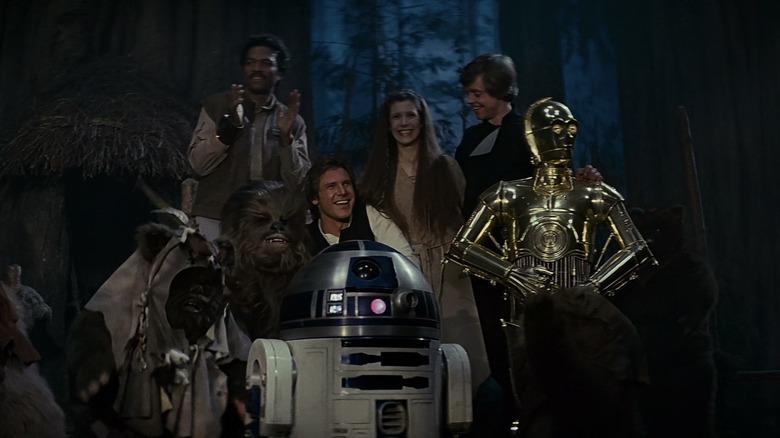

"Return of the Jedi" stages its final act by cross-cutting in and around a "second dreaded Death Star," the visible framework for future formulaic sequels. The movie shows the frail human under Darth Vader's mask and irises out with an image that suggests the heroes and their furry Ewok pals will all live happily ever after.

Gary Kurtz said George Lucas originally drew up an outline that would have killed off Han Solo and had Luke walking off alone "like Clint Eastwood in the spaghetti westerns" (per The L.A. Times). Kurtz described their plan as "bittersweet and poignant," more "emotionally nuanced" — sentiments they had already stoked perfectly with "The Empire Strikes Back."

Either way, "Star Wars" would have been repeating itself. It simply chose to instill "A New Hope" again — and sell toys in the process, if Kurtz is to be believed. (Harrison Ford also told ABC News, "George didn't think there was any future in dead Han toys.") Speaking to IGN, Kurtz opined that serving up "another attack on another Death Star" led to "a rehash of 'Star Wars,' with better visual effects."

At the Oscars, "Return of the Jedi" did win a Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects. Yet "Icons Unearthed" makes clear that Kurtz was out of the loop by the time of "Jedi," having been replaced as producer by Howard Kazanjian after he went over budget on "The Empire Strikes Back." Kazanjian relates this telling anecdote in the docuseries:

"I was in London to prepare, and Gary walked in. He said, 'Hey. What are you doing here?' And I told him that I was doing work with the crew for the next 'Star Wars' picture. And, yes, he turned white because he hadn't been told. He says, 'George never told me.'"

'The end of Camelot'

By the time we get to Starkiller Base in "The Force Awakens," it does feel like "Star Wars" has become too reliant on the concept of "another Death Star" (and even defensive about it in dialogue). "Return of the Jedi" makes it work, though, as the full-throttle Rebel assault on the second Death Star unravels with the immortal Admiral Ackbar line, "It's a trap!"

If a movie is made and remade three times over in the writing, directing, and editing, then as much credit should go to "Return of the Jedi" editors Marcia Lucas, Duwayne Dunham, and Sean Burns, as the triumvirate of George Lucas, Lawrence Kasdan, and Richard Marquand. In "Icons Unearthed," Dunham says Marcia Lucas "was the heart" of the Lucasfilm family and, "There wasn't an emotional or dramatic scene that didn't pass through Marcia's hands."

Lucas herself says, "Everything that had emotion, George wanted me to cut." Not every emotion in "Return of the Jedi" tracks with "The Empire Strikes Back," mind you. Han Solo's war-room reunion with Lando Calrissian after he gets his sight back is entirely too affectionate and smiley when juxtaposed with all the mistrust and betrayal they went through in Cloud City. However, this goes along with shielding younglings in the audience from the Dark Side, where Han might have held a grudge and ended his bromance with Lando.

In reality, George Lucas announced his divorce from Marcia Lucas just three weeks after "Return of the Jedi" hit theaters. As Howard Kasanjian says in "Icons Unearthed," "When Marcia and George divorced, we all hurt. It was the end of Camelot in some respects." Yet for the sake of the moviegoing public, they held it together long enough to bring this trilogy across the finish line and keep it situated in the "New Hope" wheelhouse.

From an adult point of view

A swell of John Williams music and classically trained thespian Alec Guinness enable "Return of the Jedi" to sell the retcon that the already Force-sensitive Princess Leia (as shown in her Bespin rescue intuition) is Luke Skywalker's sister. Luke still spits Obi-Wan Kenobi's line, "A certain point of view?!" right back in his Force-ghost face, as if anticipating the incredulity of some adult viewers.

For the generation of "Star Wars" kids who grew up watching the movies on VHS, it became an accepted part of the mythology that Leia was Luke's sister. The urge to deny that now feels more like a product of the internet facilitating a viral spread of ideas, even ones that used to be limited to offline/offbeat fan discussions of the kind seen in Kevin Smith's "Clerks," when they're talking about all the independent contractors who died on the second Death Star. This, too, betrays a retcon instinct, whereby fans now act as the stewards of "Star Wars" history and feel free to overthink it, fill in the gaps, and rewrite it when necessary.

In "Return of the Jedi," Carrie Fisher and Mark Hamill also make the retcon emotionally believable during their nighttime scene in the Ewok village. That said, the specter of twincest does retroactively hover over Leia and Luke's defiant medical bay kiss in "The Empire Strikes Back." In "Return of the Jedi," Leia's reaction — "I know. Somehow, I've always known" — also goes against what Hamill told CNN in 2004 about his own reaction to the reveal that Leia is Luke's sister:

"We didn't know. In fact, I tried to get George [Lucas] to admit, I said, come on you made that up on the plane ride over here. He said, no, I had the whole thing written."

'There is another Skywalker'

As Michael Kaminsky's unauthorized book "The Secret History of Star Wars" notes, making Leia and Luke Skywalker siblings allows "Return of the Jedi" to tie up loose narrative threads, such as the love triangle between them and Han Solo, and Yoda's stray line from "The Empire Strikes Back," where he says Luke isn't the galaxy's last hope because "There is another." Yoda adds to that line with his dying words in "Return of the Jedi:" "There is another Skywalker."

Saving nothing for the sequel, the film then swiftly resolves who this third mysterious Skywalker is, giving closure to what could have been another whole film trilogy involving Luke's sister (via TheForce.net). Gary Kurtz once told Film Threat that, in the original idea for a follow-up to "Return of the Jedi," Leia was not Luke's sister:

"She's not his sister that dropped in to wrap up everything neatly. His sister was someone else way over on the other side of the galaxy and she wasn't going to show up until the next episode."

Ultimately, Leia is and always will be Luke's sister, even if she wasn't always intended to be. The sequel trilogy, meanwhile, would come in a different form when Disney took ownership of "Star Wars." Instead of a woman named Nellith (per Leigh Brackett's first draft for "The Empire Strikes Back"), we got Rey (Daisy Ridley) adopting the name Skywalker over her true Palpatine family heritage in "The Rise of Skywalker." Yet the original "Star Wars" trilogy is self-contained enough, thanks to "Return of the Jedi," that if the viewer doesn't like how the sequel trilogy developed, they can simply ignore "The Rise of Skywalker." It's just one more reason why, forty years later, "Return of the Jedi" is the gift that keeps on giving.

Ewok Harvest: 'Horror beyond imagination'

Sometime in the last four decades, people began to break off from "The Caravan of Courage" and turn to the Dark Side, where it's fashionable to hate on Ewoks. Besides a cameo in "The Rise of Skywalker," "Star Wars" itself has largely avoided the Ewoks onscreen since the mid-1980s, as if it, too, were embarrassed by them.

If you really want to play "Clerks" with "Return of the Jedi," you could argue that the hipster aversion to Ewoks stems from not thinking through every dark implication that the film has to offer. Keep in mind, while it was in production, "Return of the Jedi" masked its true nature as a big-budget "Star Wars" sequel with the working title "Blue Harvest" (namesake of the future "Family Guy" special) and the tagline "Horror beyond imagination."

From a certain point of view, the Ewoks bring a bit of subversive black humor to "Return of the Jedi." They're cuddly people-eaters who are so intent on roasting Luke Skywalker, Han Solo, and Chewbacca over an open fire that they won't even heed C-3PO, who they worship as a golden god.

When Leia emerges in their village in her "Ewok celebration outfit" (as a Kenner action figure once labeled it), we're left to surmise that this convenient change of clothes was probably leftover from another woman the Ewoks ate. Forget those kid-friendly Ewok TV movies. If Lucasfilm wants to stay relevant in the age of "Pooh: Blood and Honey," it should consider loosening the franchise belt enough to explore the "Cannibal Holocaust" possibilities of an Ewoks horror prequel.

I don't need to know how Han got the name Solo. I need to know what happened to the sacrificial virgin who first wore that Ewok celebration dress.

A Vietnam War refresher... on LSD

Questioning whether the Ewoks, with their primitive, forest-moon, catapult-and-hang-glider tactics, could realistically hold their own against an entire legion of the Emperor's best troops ignores the devastating losses they suffer in "Return of the Jedi." One is shown mourning its fallen comrade (thinking of it as a mate who will miss the next Life Day twists the knife deeper) after an AT-ST chicken walker (designed from scrap by Joe Johnston) blasts the life out of it.

In 2005, George Lucas told the Chicago Tribune that "Star Wars" was "really about the Vietnam War" and how "democracies get turned into dictatorships." America, which is looking more Empire-like every day, lost the war. Denying that truth, as it could be applied toward the Empire losing the Battle of Endor, flirts dangerously with the Emperor's own sentiments about the "pitiful little band" of Rebels that threaten his Death Star.

All of this is below the surface of "Return of the Jedi." While it's fun to imagine the Ewoks eating the Stormtroopers whose helmets they drum at the end, what's onscreen in the Endor scenes and most scenes is an otherwise lighthearted affair that revels in alien languages and droid-speak and remains unparalleled in its creature effects.

"Mad God" director Phil Tippett, who first fleshed out the cantina scene with better aliens in "A New Hope," came up with a winning maquette design for Jabba the Hutt after Lucas referenced "Casablanca" actor Sydney Greenstreet. Tippett later admitted, "I took LSD when I was working on 'Return of the Jedi,'" which is maybe how he conceived of such grotesqueries as the Rancor monster, "a cross between a bear and a potato." Many have tried and failed to dream up anything half that inspired again as a weightless computer-generated image.

The shadow of George Lucas Sr.

Both "Icons Unearthed" and another 2022 docuseries, Lawrence Kasdan's "Light & Magic" on Disney+, help illuminate how George Lucas's relationship with his own father might have informed that of Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader. In "Light & Magic," Lucas says:

"My father wanted me to go into the stationary business and run an office equipment store. He built it up for me, and for me to take over. And I said I don't want that. I'll never work at a job where I have to do the same thing over and over again every day. It was probably the biggest disagreement we ever got into."

According to The Atlantic, Lucas Sr. "was known as a 'domineering, ultra right-wing businessman.'" It gives new meaning to the Emperor's line: "By now, you must know that your father can never be turned from the Dark Side." In "Icons Unearthed," we hear the Lucas Sr. mantra, "Own your own business. Control your own fate," and Marcia Lucas says:

"I saw George [Jr.] the happiest when he was building those buildings, when he was building the [Skywalker] Ranch. Walking around the buildings when they were being built, he loved that. Because of the small business that his father had built from nothing, George always said to me, 'I've got a company now. I have a company. This is my company, and I will never, ever sell my company.'"

Things change, and in the end, Lucas did sell his company to the "white slavers" at Disney, as he once called them, further corporatizing Lucasfilm to the tune of $4 billion. He had ruled the galaxy, and by "Return of the Jedi," he had become successful enough to hope for a father-son reconciliation and give "Star Wars" an aspirational ending, true to its beginnings.

The circle is now complete

Keeping the sequel rights to "Star Wars" and self-financing "The Empire Strikes Back" let George Lucas end the greatest movie trilogy of all time on his own terms in "Return of the Jedi." Yet it came at a high personal cost and marked the turning point at which "Star Wars" became "The Tragedy of Darth Vader," both onscreen and offscreen.

The 2004 documentary "Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy" ends with a moment of self-reflective candor from Lucas, where the same maverick who resigned from the Directors Guild of America draws an overt link between himself and Vader. These words, addressing the original trilogy, came while the prequel trilogy was between "Attack of the Clones" and "Revenge of the Sith:"

"What I was trying to do is stay independent so I could make the movies I wanted to make. But at the same time, I was sort of fighting the corporate system, which I didn't like. And I'm not happy with the fact that corporations have taken over the film industry, but now I found myself being the head of a corporation. So, there's a certain irony there, is that I have become the very thing that I was trying to avoid, which is basically what part of 'Star Wars' is about. That is Darth Vader. He becomes the very thing that he's trying to protect himself against."

"Star Wars" is now a corporate construct, through and through, and together with Industrial Light & Magic, it's long since left the warehouse for a sleek Volume soundstage. Forty years on, notwithstanding obnoxious Special Edition revisions, "Return of the Jedi" still whizzes along like a custom speeder bike with a healthier engine than any of the post-1983 models.