X2: X-Men United Adapted The God Loves, Man Kills Marvel Comic Arc, But It's Missing One Key Element

"X2: X-Men United" was released 20 years ago, and it remains easily the best of the original "X-Men" trilogy and one of the first hints that superhero movies were a Hollywood heavyweight. Even so, "X2" isn't free of the sin that many adaptations commit. Namely, not honoring the source material's spirit.

The most influential "X-Men" writer is Chris Claremont. He wrote the series from 1975 to 1991, rescuing the comic from obscurity in the process. He also gave the setting the political backbone for which it's now known. Stan Lee retroactively claimed he based Professor X and Magneto on Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, but read his "X-Men" stories and you won't find credence for that or much of a bite at all. Lee was, in the words of "Marvel Comics: The Untold Story" author Sean Howe, "a master fence-sitter."

Claremont, though, had a firmer spine. Magneto being a Holocaust survivor? That was his idea. Claremont's "X-Men" is certainly not flawless (his handling of race can definitely be eyebrow-raising), but it's trailblazing all the same. His political streak is strongest in the standalone graphic novel "X-Men: God Loves, Man Kills" (written by Claremont, art by Brent Eric Anderson).

The movie hits the same story beats as the comic: the villainous William Stryker desires to exterminate mutant-kind, so he abducts Professor X to turn his telepathy into a mutant-killing superweapon. Now sharing a common enemy, the X-Men and Magneto join forces.

However, the movie changes Stryker from a Christian minister into a U.S. Army Colonel. This guts the thematic resonance that makes "God Loves, Man Kills" a modern classic.

Men made in divine image

"God Loves, Man Kills" was published in 1982, at the height of the Moral Majority's power. Claremont and Anderson set out to comment on the rise of televangelism – the latter invoked Pat Robertson – and underline its hypocrisy. Christianity's teachings are of love and forgiveness, but its loudest followers voice only hate. And boy, oh boy, does Stryker hate.

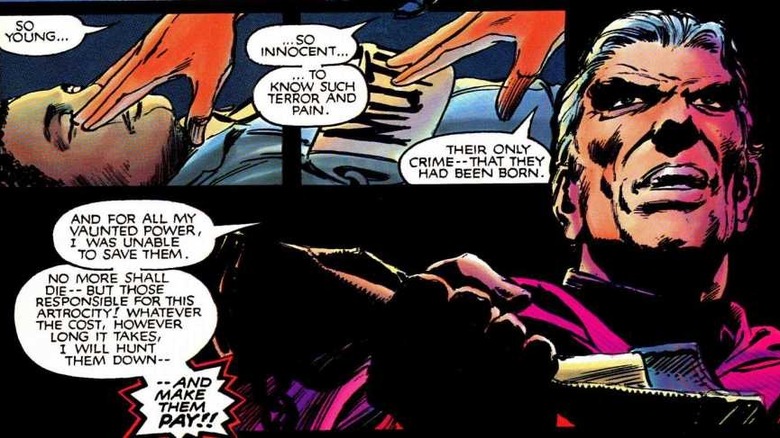

His forces, the Purifiers, are introduced by executing two mutant siblings. To eliminate any subtext, both the children (Mark and Jill) are Black, and Magneto discovers their corpses strung up like lynching victims. Why does Stryker hate mutants? His own son was one — so he killed the boy at birth and then his wife Marcy too for creating an "abomination." He proudly declared himself free of sin and that God intended him to wage war on the mortal spawn of Satan: mutants.

Of the X-Men, Stryker takes particular umbrage at Kurt Wagner/Nightcrawler, who resembles a blue-skinned demon (despite being a practicing Catholic). When Stryker asks, "You dare call that thing human?!" Kitty Pryde answers back, defending Kurt's humanity.

Claremont and Anderson's theological critique is almost as old as Christ himself. It's been made by Martin Scorsese ("The Last Temptation of Christ"), Al Franken ("Supply-Side Jesus"), Philip Pullman ("His Dark Materials"), and far too many others to list.

What makes it stand out is that it transpires in a Marvel superhero comic. The X-Men had lived in a world that "hates and fears" them for a while, but "God Loves, Man Kills" makes it feel more real because, in real life, extremist religious groups are the go-to refuge of hateful zealots. Just look at ongoing attacks on the LGBTQ+ community right now.

The button that "God Loves, Man Kills" pressed was just too hot for "X2."

Why the changes?

The fact is, "X2" was seen by a much wider audience than that which read "God Loves, Man Kills." While the United States of America is not a Christian nation, it does have a lot of Christians in it. If "X2" kept Stryker as a fanatic televangelist and the themes of "God Loves, Man Kills," it would no longer be the four-quadrant blockbuster it needed to be. Let's not forget the zeitgeist of 2003 either: an Evangelical Christian was President of the United States, a sure sign of a movement's cultural dominance. Religious boycotts have sunk movies in the past, so 20th Century Fox chose to play it safer with the $110+ million investment that was "X2." It's understandable why they did. It's not commendable, but it's understandable.

There's a narrative reason for changing Stryker too. In the film, he's the commander of Weapon X, the program which gave Wolverine his Adamantium-coated skeleton. The first "X-Men" movie teed up the mystery of Wolverine's origin, and as the series' most popular character, he had to be a central part of "X2." Making Stryker a military operator and connecting him to Logan streamlines the story in a beneficial way.

Not that bad

Despite the changes made in adapting "God Loves, Man Kills", the "X-Men" movies didn't completely run away from the comics' themes of prejudice and oppression. In "X2," Iceman (Shawn Ashmore) has a coded coming out to his family; his mother asks him, "Have you tried not being a mutant?"

Claremont's origin story for Magneto? That's an integral part of the movies too. One of the few redeeming moments of "X-Men: The Last Stand" is when Magneto is asked to show his markings of Mutant Pride. So he brandishes his prisoner number tattoo from Auschwitz, saying, "I have been marked once, my dear, and let me assure you: no needle will ever touch my skin again."

If anything, superhero movies made since are even less brave about tackling social issues. The Marvel Cinematic Universe has honored the Stan Lee tradition of fence-sitting. "Captain America: Civil War" takes the explicitly political conflict of the "Civil War" comic and turns it into a personal clash between Captain America (Chris Evans) and Iron Man (Robert Downey Jr.), to the point where the Sokovia Accords feel redundant, and it hasn't gotten much better since then.

The "X-Men" movies are quaint viewing in the 2020s, but they stand as a reminder that it's time to go forward, not backward.