The 10 Most Disturbing Details In Starship Troopers

"Starship Troopers" failed to land when it opened in November 1997. Casper Van Dien and Denise Richards were not bankable leads, and audiences expecting a conventional sci-fi epic were thrown off by the film's curious style, which is a mix of televisual soap operas and satirical militarism. Consequently, "Troopers" received a mediocre "C+" from CinemaScore and grossed just $121 million against a $100 million budget (via The Numbers).

Critics were not best pleased, either, especially Stephen Hunter, who attacked "Troopers" as a film that "presupposes" Nazism. Such literal-mindedness misses that Paul Verhoven's film is satirical meta-propaganda, not a cosmic fascist fantasy. The numerous propaganda bulletins make this clear, but the propaganda does not stop there. These bulletins are propaganda within propaganda because "Starship Troopers" can be viewed as one big propaganda piece vetted by the United Citizen Federation, the film's dystopian one-world government.

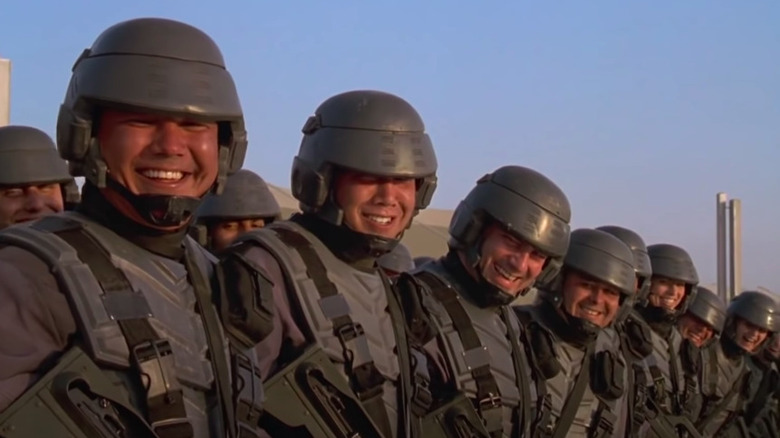

Johnny Rico (Casper van Dien) and Carmen Ibanez (Denise Richards) are model recruits, and they come straight out of Leni Riefenstahl's central casting. They are not people but icons of a violent struggle that is wryly depicted as noble, valiant, and even intimate. No opposition is allowed because unlike "Robocop," Verhoeven's earlier satirical sci-fi film, "Starship Troopers" is not a drama but pseudo-propaganda, and it relates disturbing details of real-world tyranny from the past, the present, and, alas, the likely future.

State media uses propaganda to radicalize the masses

"Starship Troopers" opens with a propaganda newsreel that urges viewers to do their part for the United Citizen Federation and join the mobile infantry. This, the narrator says, will be their contribution to saving the world.

"Would you like to know more?" asks an intertitle before, seemingly without our volition, moving to a sequence informing us of the Bug menace and the threat it poses to humanity. We're told that they inhabit a planet called Klendathu, which has an "unlimited supply of bug meteorites" that are being fired toward Earth. "To ensure the safety of our solar system," declares the narrator, "Klendathu must be destroyed." How do the masses know that it is the Bug homeworld that's firing these meteors toward Earth? They don't, they just accept what the marketing tells them, and it further radicalizes young recruits such as Johnny Rico and Carmen Ibanez, who are the latest footsoldiers in the interminable battle against the Bugs.

The Federation is in a state of perpetual war

In George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four," the totalitarian superstate Oceania is locked in perpetual war with its rivals Eurasia and Eastasia. To ask why Ingsoc, Oceania's evil government, commits itself to this violence risks detainment and death, so the masses give in to the hate and muster whatever quality of life they can.

"Starship Troopers" has little of the grit and misery found in Orwell's novel. We see only what this meta-propaganda film allows us to see, and it suggests that most of society's ills are external. They are the fault of the Arachnids. This is how the United Citizen Federation justifies its perpetual war, and Johnny Rico and his comrades accept it without question.

Are they right to trust a regime that is so clearly enamored of violence? Did 100,000 people really die in an hour during the invasion of Klendathu, or was this misinformation intended to radicalize troops at home and across the universe? These concerns are ancillary to the ultimate question: Why would the United Citizen Federation or any other government, real or fictional, want to commit itself to perpetual war? The shortest answer is control and money.

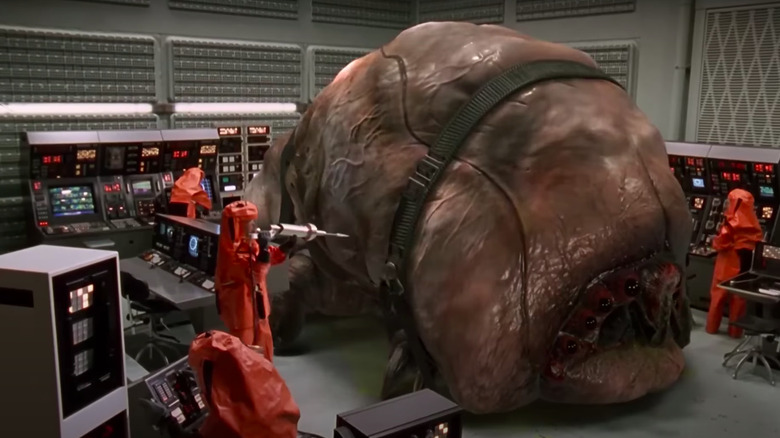

The Federation degrades its enemy and dehumanizes its people

The Arachnids may appear bestial, but that does not mean they are without intelligence. On the contrary, the Arachnids are led by what the Federation calls "Brain Bugs," which can learn, strategize, and adapt. This knowledge affords little empathy for the Arachnids, though. No detailed explanation is given as to why the Bug is an enemy of the United Citizen Federation. We are told nothing of when and how the conflict started. Such information is vital to diplomacy, but the Federation doesn't know diplomacy, only war.

There is at least some respect for the Bug's capabilities. Early in the film, during a gory biology class, a lab-coated teacher expounds on the Arachnids' numerous superiorities, "it reproduces in vast numbers, has no ego, has no fear, doesn't know about death ... and so, is the perfect selfless member of society."

What the teacher observes in the Bug is what the United Citizen Federation wants in its people: an absence of individual thought combined with a fearless resolve to fight to the death.

Only military veterans can be citizens

The Civil Rights Bill of 1866 declared that all people born on U.S. soil, with the exception of Native Americans, were citizens of the United States of America (this right was extended to Native Americans in the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924). However, the United Citizen Federation, which appears to be the United States' successor, does not subscribe to the notion of jus soli ("right of the soil"). Instead, the Federation enforces jus militaris or "right of the military," which means that only after military service will civilians be afforded citizenship and the right to vote, although the forces of democracy are likely ceremonial in the United Citizen Federation.

"What's the moral difference, if any, between a citizen and a civilian?" asks teacher Jean Rasczak (an ever-menacing Michael Ironside). Without hesitation, Johnny Rico answers, "A citizen accepts personal responsibility for the body politic and defends it with his life. A civilian does not." Rasczak is unimpressed by what he considers a fluent but glib response, and he asks Rico if he truly understands it, but the real question is whether Rasczak understands it, not Rico. Does Rasczak think that the United Citizen Federation is an open and transparent government? Does he think that the Federation is innocent and the Arachnids are wanton brutes? When he appears later in the film in combat gear, with a bionic arm, and an assault rifle, it appears the answer is a resounding "yes."

Corporal and capital punishment are used to keep civilians in line

The U.S. military banned flogging in 1861, but the United Citizen Federation uses corporal punishment with a vengeance. When a man is shot dead in a training exercise on Johnny Rico's watch, the recruit receives 10 lashes. It's a rather lenient punishment in a society steered by violence, but that's because Rico is the all-American hero in this meta-propaganda film.

Ace Levy (Jake Busey) isn't so agreeable to the military leadership, especially Sgt. Zim (Clancy Brown) who disciplines Levy not with push-ups, solitary confinement, or formally sentenced lashing but by throwing a knife into the soldier's open hand, pinning it to a wall. This demonstrates that corporal punishment by spontaneous impalement is just a matter of managerial discretion.

A propaganda segment shows us the Federation's culture of capital punishment. An alleged murderer is paraded in court before the camera moves to the execution chamber, which appears to facilitate lethal injections. This may appear similar to the American 21st-century experience, but the devil is in the details. The narrator announces that the man was captured "this morning" and tried, convicted, and sentenced shortly thereafter, which amounts to borderline summary execution. You may miss that disturbing detail, but you won't miss the narrator's parting publicity, "Execution tonight at 6, all net, all channels."

Propaganda is aimed at children

In the film's opening propaganda film, we see a mass of soldiers preaching about doing their part. Then, a child appears, helmet in hand, and says, "I'm doing my part, too!" The Federation uses this for comic effect, but there is a sinister agenda here, too. The Federation is in constant need of soldiers, and it knows that children's malleable minds are vital in securing this human stream. Children conditioned by militarism are far more likely to oblige notions of service and sacrifice — no matter the purpose.

Later propaganda targets children more directly, including one titled "A WORLD THAT WORK," which shows Federation soldiers handing their assault rifles to a group of children, who play and fight over the equipment while the soldiers snicker. Another scene, "DO YOUR PART," features neighborhood kids stomping on cockroaches, much to the maniacal glee of a nearby parent. We see the grim result of this brainwashing when Johnny Rico is given his own unit, the so-called "Rico's Roughnecks," which is no more than a band of kids sent to make up for the Federation's losses in the invasion of Klendathu.

There are numerous precedents of dictatorships targeting children. Nazi Germany's Hitler Youth and China's Red Guard recognized the power of young, radical minds, and North Korea's Socialist Patriotic Youth League still does.

Schools teach that only violence can bring stability

The first view of civilian life we see is a classroom scene with Jean Rasczak lecturing on power and governance. "When you vote, you are exercising political authority, you are using force," Rasczak explains, "and force, my friends, is violence, the supreme authority from which all other authority is derived."

He's not wrong. This has been true of humanity since time immemorial. Today, the citizens of developed countries give the state a monopoly on violence in exchange for security. This unipolarity of violence is better than its opposites, bipolarity and multipolarity, which spell the end of order and nationhood and the beginning of chaos and civil war.

Not everyone is convinced, though. When Dizzy (Dina Meyer) suggests that "violence doesn't solve anything," Rasczak dismisses her point as wishful thinking and adds, "Naked force has solved more issues throughout history than any other factor." One could argue that Rasczak is a pragmatist, but his rhetoric goes beyond notions of realpolitik. Rasczak is a hardened Federation ideologue, and he toes the party line, which dictates that problems are to be solved with violence and violence alone.

The Federation covers the globe

Johnny Rico and his peers appear to be English-speaking Americans, but they don't live within the borders of the 21st-century United States. They don't even live in North America. Instead, they live in Buenos Aires, the former capital of Argentina. Now, it's just another outpost of the Federation and its one-world government.

The Federation's vast size recalls the Oceania superstate of George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four." Oceania, like the Federation, covers Britain, the Americas, southern Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. "Starship Troopers" does not specify whether the Federation controls Africa or the Antipodes, but it does refer to a conference held in Geneva, which suggests significant control of Europe. It is likely that the United Citizen Federation has taken the world's great power centers and therefore has no Earth-bound military distractions. This is why they look to the universe for conquest and conflict, which are necessary for instilling fear, dimming critical thought, and maintaining the government's authority.

Military service kills or disables many people

We see numerous soldiers killed in battle with the Arachnids, who use their giant legs and monstrous pincers to stab and tear their enemies apart. Gorier than that are the post-battle sequences in which dozens of people lay dead and horribly mutilated. It's a showcase for the practical effects that have become uncommon in contemporary mainstream cinema.

However, more disturbing than all the gore are the veterans back on Earth who must live with serious injuries. For example, Johnny Rico and Carmen Ibanez meet a recruiter with a bionic arm when they sign up for the military. "Fresh meat for the grinder, eh?" the veteran snarks before asking for their respective services. "Infantry, sir," replies Rico, to which the vet says proudly, "Good for you! Mobile infantry made me the man I am today." He then moves backward, revealing his seat to be a wheelchair and that he is also missing both legs. The double meaning here is clear and morbid.

You need a licence to procreate

The Federation strives to control the past, present, and future of society, and an effective way of doing that is by controlling who can have children. This means that only those obviously committed to the regime are granted the necessary license. Dissenters will have their bloodlines cut short. How does one get a license? By serving, of course. It's not a prerequisite, it seems, but it certainly helps. We learn this during a gender-neutral shower scene (a favorite motif of director Paul Verhoeven) when a recruit says she joined the mobile infantry because she wants to have babies.

There is some degree of real-world precedent here. The People's Republic of China has never required a license for childbirth, but the regime did have its one-child policy from 1980 to 2016 (via Britannica). Forced sterilization has been mandated by governments across the world, too, including the United States, which sterilized some 70,000 people during the 20th century (via Berkeley).