Why Are There No Movies In The Star Trek Universe? An Investigation

While "Star Trek" takes place in a technological utopia — a utopia wherein people can teleport great distances, live in holographic environs, or replicate any food or drink they should want — there still appears to be room for old media. While the characters on "Star Trek" are typically military officers, they are often careful to attend the theater to see plays, where Shakespeare might still be performed.

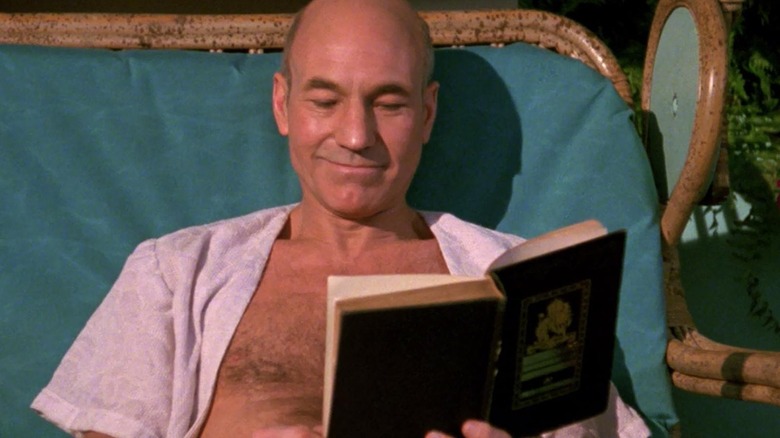

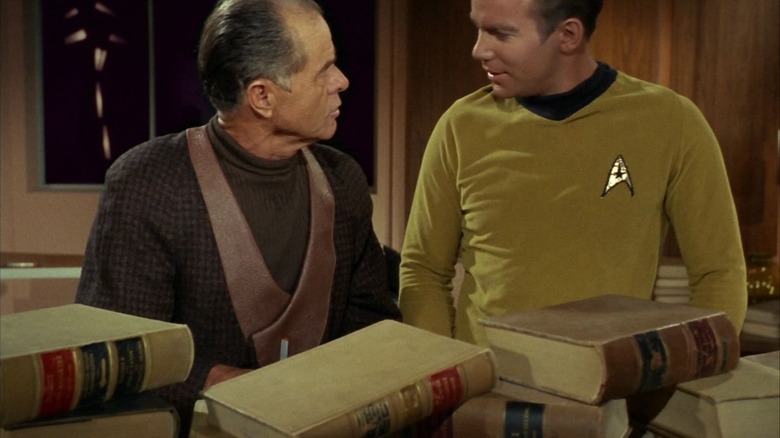

On "Star Trek: The Next Generation," there are many, many classical music concerts, and performers still seem to have access to traditional brass, woodwind, and string instruments. Entire libraries may be accessed on a PADD, and Malcolm Reed (Dominic Keating) once noted that he was attempting to make his way through James Joyce's "Finnegans Wake." But other characters may be more comfortable holding an actual printed book on bound paper. One might be able to create a force field in the future, but rest assured that there will still be "old book smell."

But while viewers may find a recognizable comfort in watching "Star Trek" characters reading books or attending the theater, they may find themselves noticing the marked absence of one particular form of media: cinema. Movies are sometimes referenced in "Star Trek," of course, as when Data (Brent Spiner) whistles "If I Only Had a Heart" from "The Wizard of Oz," but there are hardly any mentions of a character having seen "Rear Window" for the first time last night, or mention of grabbing a movie.

There are likely several reasons why cinema appears to be dead in the future, some of which are merely practical, but at least one of which may be very grim to cineastes. Let us investigate.

Star Trek: Movie Night

To address the issue right away, movies are not completely absent from "Star Trek," as they were actually regular occurrences on "Enterprise" and were resurrected for "Star Trek: Discovery." On the former program, Capt. Archer (Scott Bakula) liked to hold regular screenings, partly as a pastime the crew could share, but also to expose the Vulcan T'Pol (Jolene Blalock) to human art and culture. She was particularly intrigued by James Whale's "Frankenstein." It's implied, however, that the database of movies is limited, and the films they discuss are from Hollywood's Golden Age. This will go into a theory about the fate of cinema in the "Star Trek" timeline that I shall explore below.

Also, when the crew of the U.S.S. Discovery found themselves in a strained position, the ship's commanders boosted morale by hosting an impromptu movie night in a cargo bay wherein everyone watched Buster Keaton's "Sherlock, Jr." But while the Discovery had access to the comedy classic, one might note that the Starfleet officers merely stood around or sat on storage boxes to watch the movie. There was no "screening room" setup. This was clearly not an activity that was regularly indulged in. Sometime between "Enterprise" (set in the 2150s) and "Discovery" (set in the 2250s), films fell out of vogue.

On "Star Trek: Voyager," officers regularly visited the holodeck to reenact a black-and-white sci-fi serial created in the 1950s. See the episode "Bride of Chaotica!" (January 27, 1999). It seems the general language and influence of cinema will remain in the human consciousness as far ahead as the 2370s when the show is set. But, one might note, that the officers don't merely watch the sci-fi serial, preferring to perform in it. Which brings me to a theory:

Films were supplanted by holodecks

The first and most obvious reason for the absence of cinema in "Star Trek" is that they have been supplanted by holodecks.

The kind of space needed to house a theater on a starship would be too great to be practical. All the larger spaces that could be used as a screening room, as mentioned above, would have to be repurposed work areas, and there will be few moments when someone isn't working. The larger recreational facilities are either communal (game rooms, Ten Forward, etc.), or they're a holodeck. It seems like if one wanted to watch a movie, there is a handy-dandy technology they could use.

So let's enter the holodeck and create a simulated movie theater. One might program in the popcorn smell, the bored teenage employees, the badly-mixed Coca-Cola. If the starship archive reaches deeply enough, one could even program Nicole Kidman's infamous AMC ad. Or, better yet, why not program a simulation of the actual Nicole Kidman performing it for you live? Then you could reprogram the movies themselves to make them 3-D, but they're holograms, so actual 3-D so they physically stick out at you.

Or, if you're already going that far, you could just enter the movie.

Watching images play themselves out on a screen almost feels moribund when you can literally step inside whatever movie you want. A holodeck is too tantalizing a technology to resist, and cinema merely evolved into an interacted, performative past time. Why watch a Dixon Hill mystery when you can actually be Dixon Hill? Why watch a superhero when you can fight villains yourself? Why watch a sex scene ... Wait, is that allowed on a starship? It's entirely possible that cinematic interactivity has altered by the 24th century.

Commercial entertainment has no place in a post-capitalist world

In a previous "Star Trek" essay, I posited that creator Gene Roddenberry's future features no modern pop music. While modern pop will likely be in the public domain by Trek's timeline, it still requires royalty payments in ours. As such, there is going to be a commercial dimension to contemporary pop hits that is kind of inescapable. Modern viewers would know that some money had to exchange hands to get the Beastie Boys' "Sabotage" onto the show or into a film, and that knowledge would taint the anti-capitalist leanings of Roddenberry's utopia. In the future all art is free. In the present, it isn't. Only once music or art becomes public domain will "Star Trek" writers feel comfortable including it in an acceptable future artistic canon. As such, a lot of classical music and older books appear on "Star Trek."

While there are many movies in the public domain — great horror movies like "House on Haunted Hill," "Carnival of Souls," and "Night of the Living Dead" are free — the vast bulk of them are still commercially owned by a studio. Images and music from films would need to be licensed to show on "Star Trek," and viewers know this. This is why the movies on "Enterprise" and "Discovery" were both from the 1930s and the 1920s respectively. One couldn't show a modern 20th Century Fox logo on "Star Trek" without viewers thinking 1) of the recent acquisition of the studio by Disney, and 2) that Paramount owns "Star Trek." There would be far too much internal politicking going on to assume that everything is clean in terms of money. The commercial aspect of modern cinema is too thick to untangle from a post-capitalism future.

They were all destroyed

The grimmest reason that cinema may be absent from "Star Trek," however, could possibly be that all films were destroyed in future wars. Part of the lore of "Star Trek" is that modern humanity needed to drive itself to the brink of nuclear extinction before it was able to build its utopia. Humanity went through the Eugenics Wars, as well as World War III, and wiped out a great deal of its own population, driving survivors into a country-less wasteland surviving on scraps. It was during this post-apocalyptic time that Zefram Cochran built the very first vessel capable of faster-than-light travel. When taking his ship on its inaugural run, it attracted some traveling Vulcans who happened to be nearby. The Vulcans landed, humanity was humbled that they weren't alone in the universe, and the timeline on utopia began.

It's entirely possible that all digital film prints and even physical 35mm celluloid prints were wiped out during this time. There are records of films, and Tom Paris (Robert Duncan McNeill) from "Star Trek: Voyager" often talked about early 20th century cinema, but his access to it might have been limited. Paris managed to arrange old-world TV broadcasts using a recreated television set in his quarters, but none of the other crew members seem to share his nostalgia for such ancient objects. When most of an art form is wiped out, and new technologies provide superior experiences, why bother tracking down the old? Unless you are a history buff or a museum curator, cinema can like be seen as dead. After all, how many of us in 2023 are bothering to track down old zoetropes?

It's kind of heartbreaking. But then, heartbreak feels good in a place like this.