Children Of Men's Car Scenes Called For Inventing Brand-New Camera Tech

This post contains spoilers for "Children of Men."

One of the greatest movie scenes of the 21st century comes early in the dystopian sci-fi masterpiece "Children of Men," as five characters pile into a car for what initially seems like a blissful ride. Though the near future they inhabit is beset by human infertility, all is going well as our protagonist, Theo (Clive Owen), wakes from a backseat nap and begins playing a game with the mother of his late child, Julian (Julianne Moore). She turns from the passenger's seat, and they blow a ping pong ball back and forth, laughing right up until the moment when a flaming car comes rolling downhill ahead of them, followed by a band of marauders, the Zeds.

What follows next is the kind of movie scene the phrase "tour de force" was invented for. As they took to the road in (or, rather, on top of) a modified Fiat Multipla, director Alfonso Cuarón and his crew overcame a logistical nightmare to keep the camera running for an epic long take inside a moving car in "Children of Men."

When the Zeds attack, Luke (Chiwetel Ejiofor) puts the car in reverse before it's hit with a Molotov cocktail and two assassins ride up on a motorcycle, shooting Julian and leaving her to bleed out in Theo's arms. Theo even kicks the door open and causes the motorcycle to flip, and then we see the gunshot hole in the windshield spread until it cracks and breaks. All the while, the camera keeps rolling, looking all around in the heart of the action, but never looking away.

Needless to say, pulling off such an elaborately choreographed scene in real time was no easy feat. In fact, it required the improvisation of a whole new camera rig.

'You can't fit a camera crew in a car'

In the behind-the-scenes featurette "Under Attack" on the "Children of Men" DVD, crew members discussed the complicated process of shooting such a fluid, car-based action scene with few cuts. Producer Eric Newman observed the difficulty of achieving the "full range of vision" Alfonso Cuarón wanted while having stuntmen and actors both inside and outside the car during the ambush. "You can't fit a camera crew in a car," he said. Therein lay the problem.

Cuarón considered going green screen before he and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki devised what Newman called an "unbelievable piece of machinery" that enabled them to meet the technical challenge of the full, five-minute car scene. As camera operator Frank Buono explained, the two-axis dolly is a rig with "the Sparrow Head from Doggicam and two power slides, which work together to move the camera in and out, forward, backwards, right and left." This made it possible to "put the camera anywhere inside of this moving vehicle and be able to look around 360, out the window, and never see any rigging or be bothered by any obstructions."

There were already five actors in the car, but four more people — Cuarón, Buono, the cameraman, and the focus puller — were mounted on top in a specially constructed operation station. As the actors filmed their five-way dialogue and reactions, having the camera move around freely in the middle of the car kept them on their toes, since there was no telling where it would be at any given time.

For Julianne Moore, that unpredictability made her character's death scene all the more "exciting to shoot." According to Chiwetel Ejiofor, there were hinges on the car seats so they could move out of the way if need be.

Cops and Fishes

In the script for "Children of Men," there's a flip-down TV in the car scene, playing an episode of "Mr. Bean." The sliding camera rig on the ceiling didn't leave much room for that. What's impressive about the filmed version is that it's really more of a sequence, with a few short scenes strung together and the usual cuts removed.

The scope of it extends beyond the fiery roadblock to a police caravan and traffic stop where two cops wind up dead. As Luke shoots them both, the camera gets out of the car with Theo, moving from an interior to an exterior shot, where it stands and watches the car drive away before gazing down at the dead bodies on the road. This sets up a match cut to Julian's body in the woods.

Fifteen minutes later, we're back in the car with Theo for a sequel chase with more cuts. Theo and the other two passengers who were in the backseat with him before, Miriam (Pam Ferris) and the pregnant Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), become the target of another intense foot pursuit of a car past bales of hay. They're fleeing the farm hideout of the Fishes, led by Luke, who orchestrated Julian's death in a power grab, it turns out. One of the previous motorcycle assassins, Patric (future "Sons of Anarchy" star Charlie Hunnam), comes running up to the car without his helmet, only for Theo to throw open the door and knock him over again in a subtle but amusing callback.

The twist of Luke's betrayal, coupled with the shock of a big star like Julianne Moore's character getting killed off so soon, infuses high drama into the technical wizardry of the car scenes. "Children of Men" is a movie that fires on all cylinders.

Influence outside the car

In the "Under Attack" featurette, when Mike Buono remarks in passing, "It kind of feels like a little bit of a landmark-type shot that we're doing," he couldn't have known how influential the car scenes and camerawork in "Children of Men" would truly be. Alfonso Cuarón and Emmanuel Lubezki later reteamed for "Gravity," where they outdid themselves with a 13-minute, unbroken opening shot in space. The film won them each their first Oscar; Lubezki would follow it up at the 87th and 88th Academy Awards with two more consecutive wins for "Birdman" and "The Revenant." Both movies employed notable long takes, and both were directed by Cuarón's Cha Cha Cha Films producing partner, Alejandro González Iñárritu.

While earlier films like Alfred Hitchcock's single-location experiment, "Rope," were shot in one take or the illusion of it, "Birdman" and subsequent movie-length "oners" such as "1917" (lensed by Roger Deakins) broadened the camera's perspective beyond one room or vehicle to include Times Square and the trenches of World War I. In the 2020s, streaming titles like Marvel's "Hawkeye" and the Russo brothers' "Cherry" have further aped the same car technique as "Children of Men," while the big screen has continued to offer up similar feats of immersive ground cinematography, as in the one-shot battle scene in "The Northman."

As impressive as the form of "Children of Men" is, though, it would be less memorable without the story, which bristles with righteous indignation against post-9/11 injustices.

From the car to the bus

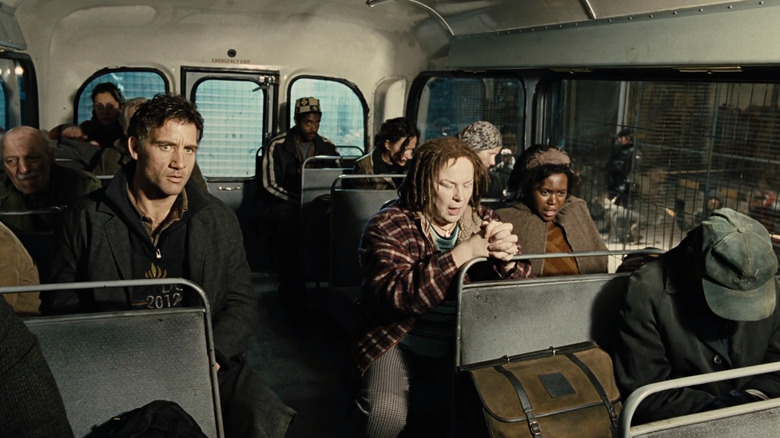

In "Children of Men," we see characters herded like human cattle onto a Homeland Security bus, bound for a refugee camp, where activity outside the windows offers more glimpses of life and death happening on the film's margins. Before the September 11 attacks, when he was best known for "Y tu mamá también," Cuarón was reluctant to take on a project of this nature. He had not read the P.D. James novel on which "Children of Men" is based, and his next project would instead be a more commercial literary adaptation, "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban." However, as a Mexican filmmaker working in Hollywood (for a studio named Universal, no less), he eventually found his way into "Children of Men" as a movie ripped from the headlines.

This was science fiction that looked to the present, rather than the future. It was unafraid to brush up against real-world politics, where anti-immigrant sentiment persists to this day. The film opens in London in 2027; in the script, it's 2024. That time seemed distant when "Children of Men" first premiered in 2006, but suddenly, Cuarón's ship of "Tomorrow" has gotten much closer to our blinking buoy in the fog. Here, the idea of a global pandemic is no longer just a prescient bit of backstory for Theo.

Using film as a canvas, Cuarón was able to capture the zeitgeist, then and now. As the closing-credits song tells us, "C***s are still running the world," but it's precisely that feeling of being caught up in the middle of larger forces — just trying to survive and hold onto some hope for the future — that gives "Children of Men," its car scenes, and all of its mise en scène, such lasting resonance.